by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 12, 2011 | Plantation Cooks

Betty Simmons sits leisurely on the back porch at 2515 Holman, in Houston’s historic Third Ward with a big, round metal pot in her lap and a curtain of voluptuous hydrangeas as her backdrop. She has a small knife in one hand, peeling what appears to be potatoes. Her white hair is brushed back away from her face, revealing a surprisingly supple and healthy look for a woman of nearly 100. The chain link of a porch swing is barely visible beyond the ornate railing.

Betty is one of five Jemima Code women who are on exhibition through June 19, at Project Row Houses, Round 34 Matter of Food. My artist friend and Peace Through Pie partner Luanne Stovall and I are co-curators of Hearth House, a traveling installation where Betty and the cooks of the Blue Grass Cook Book (the Turbaned Mistress, Aunt Frances, Aunt Maria and Aunt Dinah) are capturing the hearts of visitors just about as much as they enchant us.

Some years ago, as I fretted on a Southern Foodways Alliance excursion over the loss of these women, my friend and mentor John Egerton asked me whether they were haunting me. I shared his silly question with some artsy friends who were having their own unique, spiritual responses to the women. Before we knew it, the idea for the Project Row Houses exhibit materialized.

That phenomenal creative team (Ellen Hunt, Meeta Morrison, Luanne and I) digitized and enlarged the women’s images onto seven-foot-tall, transparent screen-like fabric that is suspended from the ceiling in one of seven shotgun-style houses at PRH.

Of course, we all knew that in order to break the code, the space had to be beautiful, so the walls were painted in warm colors that bring thoughts of sweet potatoes, sorghum and sunflowers to mind. The text is minimal — drawn from the inspirational words of Mary McLeod Bethune and from the women themselves. And, a fourth wall, painted in chalkboard paint, provides a space for the community to share kitchen memories and pie stories (which we erase periodically to symbolize the way the women were erased from history). A rough-hewn long table invites guests to linger and to leave their kitchen tales on recipe cards that will become part of our permanent archive.

When the banners were first unrolled, I actually lost my footing and crumbled onto the floor. And cried. I’d spent so many years waiting for these women to finally be honored. To top it off, on our final day of installation, my mother noticed that as I stood on the back porch of the house just beyond the screen of my favorite, the Turbaned Mistress, my silhouette was eerily superimposed into the screen like the shadow of a child, ready for tutelage at her side. Thank goodness she had the sense to photograph the moment. Obviously, the mystery of the women is very personal. And, it is palpable.

Since Opening Day, people visiting the exhibit have written to confess their experiences, too. They tell me how Aunt Frances looks over them in different ways depending upon the sunlight, or when the hot, humid breeze blows through the house at different times of day.

Is there something special to know about Betty?

Betty was one of those extraordinary slave girls, who grew up in the kitchen in the shadow of a phenomenal Texas cook who had absolutely no idea she was saving a child’s life as she passed on culinary skills casually, one meal at a time. But, she did.

Betty was born a slave to Leftwidge Carter in Macedonia, Alabama, then she was stolen as a child and sold to slave traders, who later sold her in slavery here in Texas, where her cooking skills protected her from a harsh life of field labor in slave times, and helped her manage scarce resources in freedom.

She was interviewed at a time when national pursuits – from board games and radio to mystery novels by Agatha Christie – helped Americans escape the rigors of Depression-era living, and field writers for the Federal Writer’s Project recorded the life stories and oral histories of former slaves.

Sadly, the government didn’t think to ask many questions about food and cooking, but I’m not mad at them. Fortunately for all of us, the conversational style of Betty’s narrative gives an intricately detailed look at the precarious life of a slave cook working at a Texas boarding house. I learned a little about humility, charity and self-respect from Betty. And, after months of putting the wrong things first in my life, I’m hoping she will help me get my priorities straight from today forward.

What do her words encourage you to do?

Here is a bit of her story:

When massa Langford was ruint and dey goin’ take de store ‘way from him, day was trouble, plenty of dat. One day massa send me down to brudder’s place. I was dere two days and den de missy tell me to go to the fence. Dere was two white men in a buggy and one of ‘em say I thought she was bigger dan dat,’ Den he asks me, ‘Betty, kin you cook? I tells him I been the cook helper two, three month, [Betty’s aunt Adeline was the Langford’s cook] and he say, ‘You git dressed and come on down three mile to de other side de post office.’ So I gits my little bundle and when I gits dere he say, “gal, you want to go ‘bout 26 mile and help cook at de boardin’ house?

Betty’s narrative ends with a sad revelation that her massa eventually did lose everything he owned to creditors — including his slaves. She and the remaining servants were sent to various traders — some benevolent, some harsh — in Memphis and New Orleans. Eventually, Betty the child winds up in Liberty, Texas, where she conveys a message that still resonates for for everyone trying to make it through difficult times — including me:

We work de plot of ground for ourselves and maybe have a pig or a cuple chickens ourselves…We gits on alright after freedom, but it hard at furst ‘cause us didn’t know how to do for ourselves. But we has to larn.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 3, 2010 | Plantation Cooks

Last week, Hollywood helped me imagine a place in the spotlight for the women of The Jemima Code.

A world-renowned actor and a producer appeared on “Good Morning America” to discuss their documentary film. The project tells the story of unsung heroes, tracing obscure African-Americans from the earliest days of the republic through today. Historical documents illustrate the struggle. Archival materials expose unknown contributions to American culture. Dramatic and emotional readings by noted Hollywood personalities give life to their thoughts.

The film is called For Love of Liberty: The Story of America’s Black Patriots, but it could just as easily have been titled after this blog: The Jemima Code: The Story of America’s Black Cooks.

Why?

Take a look at Southern cookery literature from the colonial era to Reconstruction and post-World War I and you’ll see stories of real women cooking, feeding and nurturing families as those folks went about their daily work. But you’ll have to look carefully. The recorders of history mostly overlooked the contributions made by these people.

To hear the antebellum plantation mistress tell it, she acquired a new recipe, read it to her kitchen slave, and then stood over the cook while she prepared the dish. The cook might later apply some African technique, or add a local ingredient, incorporate a leftover into it, or simply adjust the formula because of an environmental factor — like humidity or uncooperative chickens who didn’t lay enough eggs that morning. Over time the dish became something new and original – a “Southern creation.”

The “exotic-sounding preparations were first known through English cookbooks, contained various strands of direct Indian influence, and, were developed by African American ingenuity and creativity,” says historian Karen Hess, but Aunt Dinah entered history as the provider of labor.

Without property rights, the cooks lost ownership of the hybridized cuisine they created when their “soul” food, (black-eyed peas and wild greens) passed from the cabin to the Big House. They were like the slaves who produced ironwork, baskets and architecture: they transmitted their craft orally and left little written proof of their accomplishments.

Once in written form, these “new, original” American formulas were sold to an eager cookbook-buying audience, rarely acknowledging any debt owed to the servants who modified the English recipes – whether the cooks were the indentured servants of the North, or the slaves of the South.

Consider the diary of Emily Wharton Sinkler.

Emily was evidently a very busy low-country plantation mistress. In her journal and letters she describes the anticipation of arriving visitors. Mixing and mingling at the horse races. Scouring the countryside for cuttings and root clippings for her gardens, and days filled with reading, writing, music, long walks, and horesriding. The portrait of Emily also details her love of traveling and shopping in Charleston and Philadelphia, the wonderment of lavish dinner parties, her housekeeping experiences, rigorous Bible studies, and the family’s strict observation of the Sabbath.

Her receipt collection is just as full as her schedule, boasting recipes for numerous items produced by her family’s enterprise, including recipes for household cleaning solvents, dyes, soap, and candles.

Interestingly, there is little mention of Emily’s servants, even though some of her favorite dishes reflect the African influence. Like other authors of the era, Emily “consigned cooks to anonymity, depicting them in condescending caricatures as bandanna-headed mammies, and kindhearted, but formidable servants,” says culinary historian Barbara Haber. And, I can’t help but wonder: When did hard-working Emily sleep?

Fortunately for disparaged cooks like Chloe, modern copyright law validates a notion popularized by the America Eats Project, that: “The making of the masterpiece does not lie in the food, but in the preparation.”

The culinary publishing industry has long presumed, that changing a single ingredient or step in the method spawns a new dish and therefore new ownership. This standard allows that even a cook whose imagination is first stirred by a written recipe, but who substitutes key lime juice for lemon, opts for a different cut of meat, increases the amount of sweetening, or for that matter changes sugar to molasses can and should expect her name to follow the recipe title.

If that is true, then the recipes slaves like Chloe created while crossing culinary boundaries in the Sinkler household are a strong witness to the African American cook’s reputation, and testify to their value as worthy documentary subjects.

No, these women didn’t risk their lives for their country. They just provided the nourishment for those who did.

*

In the introduction to An Antebellum Plantation Household, author Anne Sinkler Whaley LeClercq writes that Emily had various receipts for pea soup, and she especially prized fresh peas. The addition of salt pork and black-eyed peas to Emily’s recipe for Winter Pea Soup shows the slave influence. I adapted her recipe for modern tastes. It is perfect for the end of winter and is dedicated to Chloe, her cook and to Maum Mary, shown above picking peppers. The dish is already rich in fiber, but if you want to make it a power-house, go ahead and stir in cooked black-eyed peas to your liking.

In Her Kitchen

Split Pea Soup

Ingredients

- 2 cups green split peas

- 1 ham bone

- 1 cup chopped onions

- 1 large carrot, diced

- 1 large stalk celery, diced

- 1 large clove garlic, minced

- Salt, pepper

Instructions

- Place peas in a large saucepot and add enough water to cover. Soak overnight and drain. Or, to reduce cooking time, bring the peas and water to boil and boil 2 to 3 minutes, then turn off the heat and cover. Let stand 1 hour. Drain. Add 2 quarts water, ham bone, onions, carrot, celery and garlic to the pot. Bring to boil, then reduce heat and simmer gently about 1 1/2 hours, or until peas are tender. Remove bone from soup and cut off the meat. Dice and return to the soup. Season to taste with salt and pepper.

Number of servings: 6

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Feb 17, 2010 | Plantation Cooks

A month into my study of black women cooking in America’s kitchens and already I can see numerous professional characteristics displayed by slave women. Plantation cooks worked under pressure and still devoted attention to detail. Fashioned a creative style under stone-age conditions from meager ingredients. Possessed exceptional organizational skills.

But, it was their forebearing management style that caught my attention this week, following popular British chef Jaime Oliver’s TED challenge that Americans take back responsibility for educating their children about food. If Oliver’s plans to join the Obamas and others in the fight against obesity and food ignorance seems intrusive, it shouldn’t; we live in an era when many adults become completely depressed by the thought of kids in the kitchen.

Not these women. They supervised a gaggle of helpers, some of them young children, without surrendering their hearts to despair just because of the distraction and hazard of children underfoot.

We all know that slavery’s children were exposed to heavy labor at an early age. From Works Progress Administration interviews, we also learn about the skills and traditions their mothers handed down to them as they worked side by side, which reveals a communal spirit, not weakness.

Imagine Mammy or Aunt Chloe redirecting her feelings, telling herself and her children they were allowed “to “play” in her kitchen or to “help out” with the cooking. At the same time, in an informal way, she taught them basic responsibilities, transferred culinary expertise, and instilled confidence and self-esteem, when she allowed the child to accomplish simple tasks like helping her to put on a pot of rice.

Aunt Mary Graham remembered that Mammy Rose, the cook managed the fireplace and several servants at once, including children on her Washington, Louisiana plantation. Aunt Mary was the “table gal,” who learned from the Missus how to “make it fitten fo’ fine folks ter eat at.”

A small girl, usually the cook’s daughter, carried the food to a small table near the kitchen door, then the table gal would carry the meal into the dining room. Mammy Rose, she said, “Didn ‘low no boys ter wait on tables caise dy rush roun’ so fas’ an’ spill things.”

Mandy Morrow, a former Texas slave who cooked in the Governor’s Mansion, was one also of those early trainees. She recalled carrying food pails to the field, managing the smoke in the smokehouse, making preserves, and “making sorghum molasses every year to sweeten the coffee.”

Aunt Charity Anderson, one of six house servants, explains: “My job was lookin’atter de corner table whar nothin’but de desserts set.”

I have to admit that some nights, these narratives troubled my sleep, but most times, I tried to put on my own mother apron and think about the joy I share with my children at the table. And that brought memories of my son Brandon’s Chocolate Chip Cookies to mind. His recipe is a family favorite that grew out of a challenge when he was in middle school and I was a newspaper food editor. He taunted me into a weekend cookie bake-off, which he proceeded to win with this simple, sweet recipe. I make them with the kids in my cooking classes and we still laugh about it today.

What recipe did your mother use to bring you into the kitchen?

In Her Kitchen

Chocolate Chip Cookies

Ingredients

- ½ cup margarine

- ½ cup shortening

- ¾ cup brown sugar, firmly packed

- ½ cup sugar

- 1 ½ teaspoons vanilla

- 1 egg

- 1 ¾ cup all-purpose flour

- 1 teaspoon baking soda

- ½ teaspoon salt

- 1 cup semi-sweet chocolate chips

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 350 degrees. In a large bowl, stir together margarine and shortening until mixed and light yellow. Add sugars and stir until creamy. Stir in vanilla and egg. Stir in flour, soda and salt. Blend well. Stir in chocolate chips and mix well. Wrap in plastic and shape into a 12-inch log. Refrigerate until firm. Slice cookies about ¼-inch thick or drop dough by rounded teaspoonfuls, 2 inches apart onto a lightly greased cookie sheet (or spray with non-stick vegetable spray). Bake for 8 to 10 minutes or until light golden brown. Immediately remove cookies from cookie sheet to wire racks and cool.

Number of servings: 48

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Feb 10, 2010 | Plantation Cooks

Yesterday, the First Lady announced an ambitious initiative designed to “eliminate childhood obesity in a generation.” Her nationwide campaign, entitled “Let’s Move,” was kicked off with a presidential memorandum that established a plan to evaluate and coordinate public and private services, and to improve health information so that parents can make better decisions about their children’s diets.

In a news conference announcing a multi-agency task force, Michelle Obama explained that our children aren’t responsible for the epidemic that confronts this country — 1 in 3 children is considered obese, while this country spends $150 billion each year treating obesity-related illnesses. Michelle also explained to reporters that the idea for the program came to her as a response to advice from Sasha and Malia’s pediatrician, who suggested that she “…might want to do things a little bit differently.” After all, Michelle Obama reminded viewers, it is parents who are responsible for making healthier food choices available and appealing to youngsters, and who can and should encourage kids to spend less screen time, and more time engaged in physical activity — preferably outdoors.

I wasn’t surprised at all by the First Lady’s commonsense approach to today’s confusing health messages, food labeling chaos and the dearth of wholesome, fresh food in some urban communities — what she called, “food deserts.” Michelle descends from a legacy of women who made survival in difficult times an art form.

We are all busy. Food portions are huge. Chemicals and artificial ingredients are hidden from view. And, yes, sugar is everywhere. But that does not mean we have to live as victims. With inspiration from our foremothers, we can choose dietary balance and moderation without resorting to packaged, artificial foods for convenience.

Just consider the focus, and imagination of slave cooks, unable to read or write, as they performed multiple tasks at one time, and demonstrated remarkable feats of recall, memorizing dozens of English recipes as they prepared meals in Big House and cabin kitchens. In a patriarchal system that didn’t even offer slave women control over their own sexuality, choosing a particular food, and a particular means of preparation, contributed to their sense of self-esteem because it offered them a small element of control. These women managed to maintain vestiges of their African cultural past while preparing meals for the master’s family and their own without the constant eye of the “missus” looking over their shoulders.

We can live with minimal exposure to the world’s apple, too.

The traditional view of a slavewoman’s responsibility for preparing and serving meals in her master’s hot cookshop mirrored her image as a lowly servant charged with the most onerous and arduous tasks of the household. But, the role of food and cooking took on immense cultural and ideological significance when she returned to the privacy of her home in the slave community.

Lizzie Farmer of McAlester, Oklahoma, remembers family cooking with some fondness; it was a time for women “to spend the day together,” trying out new skills and preparing fresh, seasonal foods:

“Young mistress taught me how to knit, spin, weave, crochet, sew and embroider,” Farmer told an interviewer for the Works Progress Administration. “In the cullud quarters, we cooked on a fireplace in big iron pots. Our bread was baked in iron skillets with lids and we would set the skillet on de fire and put coals of fire on de lid. When we want to cook our vegetables we would put a big piece of hog jowl in de pot. We’d put in a lot of snap beans and when dey was about half done we’d put in a mess of cabbage and when it was about half done we’d put in some squash and when it was about half done we’d put in some okra. Then when it was done we would take it out a layer at a time.”

Like French chefs who recalled their “old ways” when dealing with unfamiliar foodstuffs and working with “inferior substitutes” following wartime, slave cooks, applied “African grammar – methods of cooking and spicing from remembered recipes, and ancestral tastes to the grains, fruits, vegetables, meats of the New World,” says historian Charles Joyner. They demonstrated technical knowledge and skill, took their time, and followed directions with discipline and order.

Food rations varied little from plantation to plantation – cornmeal, pork fat, molasses, and sometimes coffee, depending upon the master, making food collecting a necessity slave women turned into a luxury to maintain cultural continuity with Africa. All across the south, black cooks enlivened the family’s monotonous diet, before and after their work day by hunting, fishing, crabbing, oystering, clamming, foraging for wild nuts, fruit and vegetables, and gardening in small plots.

They evaluated the quality of ingredients at their disposal and determined their flavor profiles. They considered how one food might work with another according to taste, aroma, and appearance. They understood the importance of food safety and maintaining freshness, and identified the proper way to store and hold various ingredients. And, they relied upon rudimentary tools such as mortars and pestles to pound out “sarakas” flat rice cakes.

Mom Hester Hunter, of South Carolina, explains that cooks balanced work and home with advance preparation and organization. In her WPA interview, she said: “De peoples sho cook dey dinner for Sunday on Saturday in dat day en time.”

Slave women also applied classic techniques (like those taught in today’s culinary academies) to common ingredients. They supplemented meager stocks and broths with fresh meat scraps. They braised meat bones and aromatic vegetables into stews; roasted wild game; stewed wild leaves and greens; thickened meal into mush; preserved seasonal fruits into jelly, substituted sweet potatoes for rice, cured ham. They coped with the differences between “tenderness and putrefaction;” understood timing, frying, poaching, sautéing, galantines, fermentation, custards, and forcemeats.

Michelle Obama’s new initiative doesn’t tell us exactly how to improve our health and slow the pace toward obesity, but even casual observers can see some clues in our ancestry: Simple, fresh ingredients. Plucked from the garden. Made from scratch. Following standard techniques. Spiced with cultural seasonings. Portion control.

What were some of your mother’s food rules? “Clean your plate; eat your vegetables?” Click Comments below to share them with us.

In Her Kitchen

Collard Greens and Turkey

Ingredients

- 3 ½ quarts water

- 1 smoked turkey leg

- 1 onion, chopped, about 1 cup

- 3 garlic cloves, minced

- 2 pounds (2 bunches) collard greens, chopped

- Salt, pepper

Instructions

- Bring water, turkey, onion and garlic to boil in a large kettle, then reduce the heat and simmer 20 minutes. Meanwhile prepare the greens. Cut off and discard about 4 inches of the stem. Stack 5 or 6 leaves, roll up, and slice greens into 1-inch strips. Roughly chop, chopping stems more than the green tops. Add greens to the turkey broth, cover, and cook over medium heat about 2 hours. Season to taste with salt and pepper.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 27, 2010 | Plantation Cooks

Another week, another feature story about Nubian Queen LoLa. What is it about this woman that keeps the media buzzing? Her humanitarian spirit as a newly-ordained minister of the Gospel? The sound of her voice emanating from the kitchen as she sings along with the blaring rhythms of Gospel Radio 1060 while fixing lunch? The tiny, crowded dining room, (you might as well call it a pulpit), where crisp hot chicken wings and seafood po’ boys come with a side of the Holy Scriptures? The backyard she has turned into a “solitary place” where the homeless find something fresh and warm to eat? Her one-time homeless status?

Curiosity and my desire to share the pies I had leftover following last week’s Dream Pie Social lured me to Nubian Queen LoLa’s Cajun, Soul Food Kitchen in Austin. I went back for the inspiration. And, the wings.

At LoLa’s kitchen table, a friend and I enjoyed a mixed menu of etouffee, collard greens, sweet tea, and life lessons that is seldom seen anymore — not in boisterous eateries, or at take-out counters, or in the rush of dinner served in front of American Idol. But there are two things to know if you decide to partake of LoLa’s: enjoy the wait, and expect to be encouraged toward greatness. LoLa is a one-woman show doing quadruple-duty as the restaurant’s greeter, cook, server, and dishwasher — a flour- and cornmeal-dusted representation of the cliche “labor of love”.

As a child in Lake Charles, Louisiana, LoLa Stephens-Bell “sat on the sacks [rice sacks]” observing her mother craft Louisiana-styled dishes as a cook for Kozy Kitchen, Captain’s Table and the Candelight Inn. Eventually, when she was old enough she says, “I told her to sit on the sacks and I’ll do it.” LoLa promised her mother that one day she would have her own place where appetites and souls are nurtured at the same time. She also planned to hire “a little old lady” like her mom as a way to give back to the community. She was on her way to that dream when a flood turned her life upside down. LoLa became homeless. “I lost everything: my husband, my house, my kids,” she said.

Since then LoLa has been cooking up a storm, drawing media raves as much for her community spirit as for her cooking. LoLa is closed on Sundays. That’s when she feeds the homeless and the poor from her shallow wellspring. Donors provide support offering everything from food, to transportation, and gift card printing. “Now, I’m coming back stronger than I have ever been in my life and I am teaching and preaching my word to the poor,” she boasted. “They are the hidden treasures of God.”

I think I understand what keeps everyone coming back to LoLa’s place. It is her generous spirit. LoLa reminded me of the ancestors who put dinner on the table in the 19th Century despite the harsh physical labor required, and who worked tirelessly for their neighbors, secretly feeding run away slaves to keep them safe for as long as they possibly could.

Back then, routine daily tasks included soap- and candle-making, clothing families, cooking over a hearth, lifting heavy pots, toting water and, of course, tending children. Without refrigeration, cooks spent a great deal of their time fetching milk from the springhouse and keeping crockery storage jars clean. Cooking took place over a raging fire, which required cooks to spend long hours every day sifting ashes, adjusting dampers, lighting fires, and carrying wood. She maneuvered elaborate utensils that were suspended on hooks of various lengths on a backbar. This contraption allowed pots, kettles and footed Dutch ovens, also known as “spiders,” to hang at various distances above the flame. Did I mention that she did this in a long skirt with children running around?

Some larger plantations had two cooks: a plantation cook and just for one for the children. Even so, the task of preparing a midday meal for up to 200 adults and more than 100 children reveals the Herculean strength required of a plantation cook. It is difficult for me today, with so many convenience foods, tools, and equipment, to imagine the physical demands of chopping wood for the kitchen fire, toting tremendous iron kettles weighing as much as 40 pounds, or to envision the enormity of turning spitted meat in a five-or-six-foot tall fireplace – by hand. And, it stretches my imagination to consider the skill it took to build that fire, measure its temperature, and calculate cooking time by the progression of the sun.

But our women did these things, in much the way LoLa does today, with minimal equipment and scarce resources, but with a lot of hard work and devotion that produces food for the belly as well as the soul. So, my friend and I sit back and take it all in. We can’t help but wonder: Where have all the faithful servants gone?

Do you know someone like LoLa who cooked and cared for her community as much as she did for her family? Please share her story by clicking on Comment below.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 6, 2010 | Plantation Cooks

Scholars tell us that Aunt Jemima was the professional persona for household slave women generically identified in literature and history as the plantation Mammy. They say that this obsession with mythical mammies obscured the work of real southern domestic servants, making them little more than a figment of the romantic imaginations of southerners, concocted from a recipe based on “not one truth but a variety of truths and lies told by different people in different circumstances at different times for different reasons.”

In order to break the Jemima Code and find a place for African American women at the long table of American culinary history, I had to forget this kind of academic wrangling about whether mammy ever existed, and instead fill in the mammy outline with clues from multiple sources, including the writings of slaveholding families, because they are the ones who left written documentation of food experiences and practices — even though slaveholding families did not make up the majority in early America.

Interestingly, when these women registered their thoughts, emotions and opinions in their diaries, household journals and letters to family and friends the writings contained few references to meal preparation except as part of the daily routine of plantation living. They state that household slaves were assigned various domestic duties as cooks, laundresses, seamstresses, nurses, and housekeepers. They dressed in the clothes of the family. Ate better food than field slaves. Received medical treatment, and some learned to read and write, despite prohibitive slave codes that prohibited educating them.

When the mistress said, “I planted 60 acres of oats today,” she usually meant she supervised the day’s agricultural chores, not that she actually did the work herself. And, according to her texts, “Chloe,” “Aunt Rachel,” and “Mammy” all cooked. By the time the mistress’s ruminations appeared on the pages of southern ladies literature, Chloe and Rachel’s contributions, their character traits, and identity fuse into one larger-than-life, simplified woman named Mammy. And, in fiction, Mammy did everything.

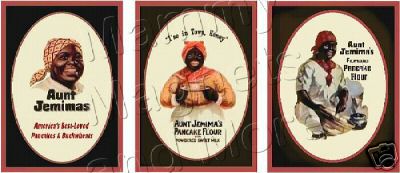

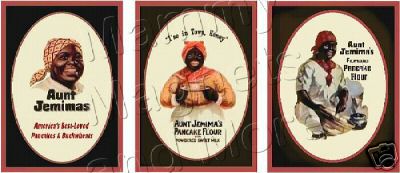

Mammy affirmed the abolitionists’ stance that slavery was bad while she maintained the segregationists’ view of social hierarchy. Post-Reconstruction Mammy, reflected the new social order, too. She consoled desperate housewives, assured neophyte cooks with creative ingenuity, and at the same time was the source of America’s increasing servant problem. Mammy defended the homestead. Mammy saved the baby. Mammy trained the children, and on occasion, the Misses. Mammy cooked from memory. Mammy made the best pancakes. And, Mammy set a table that invited everyone to come.

She inspired a “Mammy craze,” which swept the nation, between the 1890s and the 1920s, says Cheryl Thurber. In 1923, the United Daughters of the Confederacy demanded that a monument to Mammy be erected in her memory at he nation’s capital. And, in 1924, a New York shop window advertised a fascinating new style for women: an audaciously colored scarf, ‘the Paris version of mammy’s old Southern bandana.”

If we only think about an African American cook’s lowly station of life, the minimal culinary contributions credited to her by historians and cookbook writers, and the exaggerated and distorted pictures used to misrepresent her intelligence, then it is, of course, impossible to believe that she could have been anything more than a simple laborer.

Fortunately, there is an alternative view.

In 1938, Eleanor Ott published a fanciful collection of New Orleans-styled recipes, entitled Plantation Cookery of Old Louisiana, which illustrates the degree of specialization and expertise known among black cooks. In it, Ott details her grandmother’s vast “culinary plant” with its numerous adjunct buildings and “mammies” assigned to each house. At Fair Oaks Plantation, Kitty Mammy managed the vegetables and herb garden and Becky Mammy was the “high priestess of the milk-house,” while “some colored sub-cook was only too pleased to sit for eight hours…to keep an eye on a kettle of simmering pot-au-feu.”

The Culinary Institute of America’s programs catalog might define these “Mammy” tasks in a more professional way, with Kitty, Becky, and the no-named Mammy each as technicians of Vegetarian Cooking: Strategies for Building Flavor; Baking and Pastry; and Soups, Stocks and Sauces.

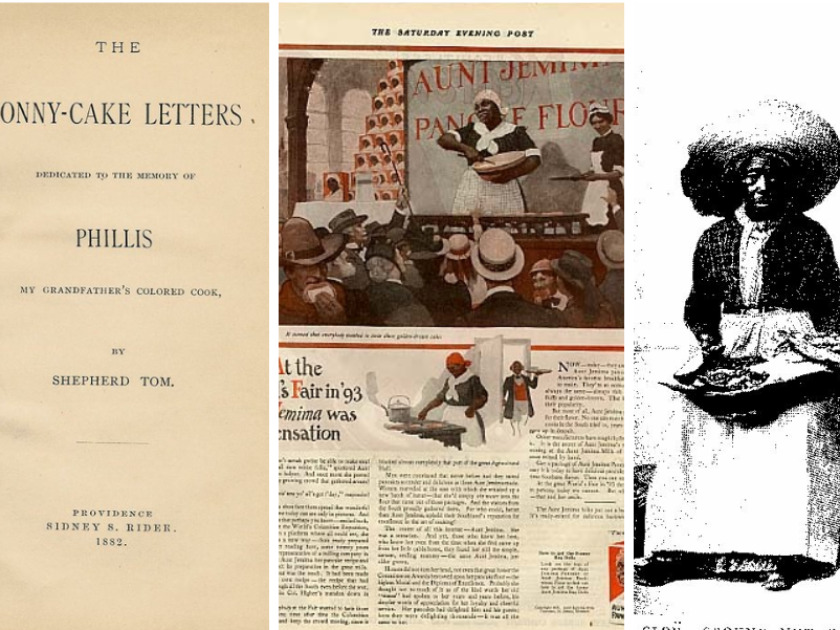

And, then there is, The Jonny-Cake Letters, Dedicated to the Memory of Phillis My Grandfather’s Colored Cook, a journal written in 1882 by Thomas R. Hazard of Rhode Island. Phillis is Hazard’s muse. She is “universally admired.” Is the “remote cause of the French Revolution and the death of Louis 16th and Marie Antoinette.” And, she reportedly bakes the most seductive jonny cake Hazard has ever tasted. Within Hazard’s exaggerated family tales are more than a few observations of Phillis’ culinary proficiency, which are so deeply enmeshed with his food recollections it is difficult to tell which comes first: his love of food or his passion for the skill of Phillis.

And, it really does not matter.

Phillis’ jonny cake “made one’s mouth water to look at it,” her assorted rye breads were “prized above rubies,” and this woman known only as his grandfather’s old kitchen cook from Senegambia or Guinea, was as an “artist” capable of inspiring others while tending the pot.

Like the assorted mammies of Fair Oaks plantation, Phillis’ culinary talents give the black cook’s shadows some substance, and there is evidence associating Mammy characteristics with real black cooks found in black sources, as well.

In slave culture, Mammy was a common name for mothers, and elders were addressed as “Aunty,” “Mauma and “Maum,” or “Mammy” as a mark of respect, not kinship. In the 1880 census the mythical Aunt Jemima is linked to at least one real, living African American woman, a black female servant who lists “cook” as her occupation and Mother Jemima as her name. The name Jemimah implied blessings and a message of hope, not subservience, according to Old Testament Scripture found in Job 42:12-14, and slaves, evidently knew it.

So, I am not at all surprised that legendary cooks and ex-slaves with a worthy name were brought to life in a marketing campaign created by a couple of guys trying to sell more pancake flour.

Are you?

In Her Kitchen

Whole Wheat Pancakes

Ingredients

- 2 cups whole wheat flour

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- 2 eggs

- 2 cups buttermilk

- 6 tablespoons unsalted butter

Instructions

- Whisk together the flour, baking powder, soda, salt and sugar. In a separate bowl, combine the eggs, buttermilk and 4 tablespoons butter. Make a well in the center of the dry ingredients and pour in the liquid ingredients. Stir together until just mixed. Batter will be lumpy. Heat a nonstick griddle over medium-high heat. Brush lightly with remaining 2 tablespoons butter, and using a 1/4 cup measure, ladle batter onto griddle for each pancake. Reduce heat to medium and bake pancakes until the top is bubbly and the edges begin to crisp, about 2 minutes. Using a wide spatula, turn pancakes over and cook on other side 1 minute longer. Do not flatten pancakes. Remove to serving platter and keep warm. Wipe griddle with paper towels, then repeat process with remaining butter and batter.

Number of servings: 4

In Her Kitchen

Comments