by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jun 20, 2014 | Featured, Kitchen Tales

What do you do when you discover something unknown to most people? You make a documentary, of course. At least that’s what my friend Adrian Miller has decided to do, and I hope you will support his very special project.

In my February 28th post, I introduced you to Adrian and urged you to read his book Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time. Since then, Soul Food won the 2014 James Beard Foundation Award for Reference and Scholarship, and just this week, Addie Broyles interviewed us for an Austin-American Statesman feature story about Juneteenth foods, including red soda water. In September, Adrian and I will share the stage at the Eat. Drink. Write. Memphis., in Tennessee, and we’re hoping to tell the story of America’s invisible black cooks next spring in Washington, D.C.

But today, I want to tell you about Adrian’s next important work: a television documentary about African American presidential chefs.

While writing Soul Food, he discovered that every U.S. president has had an African American working in their kitchen, and he’s got their stories and recipes. Adrian will profile several women (pictured above) who cooked for Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison (Dolly Johnson, circa 1887, left), Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt (Elizabeth “Lizzie” McDuffie, maid and part-time cook), and Lyndon Johnson (Zephyr Wright). (You can read more about these cooks in an essay Adrian wrote for our friend Ramin Ganeshram’s America I Am Pass It Down Cookbook.)

It’s no surprise to me that the Jemima Code runs through the White House basement!

Adrian has an active Kickstarter campaign for this documentary, tentatively titled, The President’s Kitchen Cabinet. His idea is to film a trailer that can be used to pitch the show to television network executives. He’s already raised more than 75% of the $10,000 goal, and now the campaign is in its final days (ends at midnight on June 26th).

Ordinarily, it is enough for me to share the stories of amazing women (and a few men) and their gifts to American cuisine on this blog. And, I might even give you a cute little red sticker, emblazoned with the declaration “Bringing Back the Bandana” as your badge of ambassadorship when you attend a Jemima Code talk and are moved by its hopeful message of racial reconciliation at table.

But this week, as we celebrate Juneteenth and its promise of a better tomorrow, I’m asking that you please take a moment to check out Adrian’s Kickstarter campaign, make a donation (no matter how small), and share it with others.

Together, we can help get this important work on the air in time for President’s Day 2016!

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 28, 2011 | Kitchen Tales

A warm, gentle breeze blew across the front porch at 2515 Holman causing the screenprint of the Turbanned Mistress to sway forward and back the way your grandmother might rock her chair to and fro after worship service on Sunday afternoon. It was as if she was there, watching and listening to our every word, waiting for the just-right moment to interject a remark. Which, of course, she never did.

Although her presence was felt as the inspiration for the intergenerational, gathering of women of varying cultures and backgrounds who came together on Easter weekend to share pie and kitchen memories at Hearth House, she did just what generations of black cooks always did: She simply faded into the background.

If you’ve been reading this blog, or have ever received my business card, then you know that the Turbanned Mistress is no longer living, but I keep her image alive through words, exhibits and whatever means necessary so that women like her who worked in America’s kitchens are not forgotten. She is one of five images of African-American cooks, who will be on exhibit at Project Row Houses in Houston’s historic Third Ward for PRH’s Round 34: Matter of Food from now through June 19, Emancipation Day.

I couldn’t help but notice the irony.

There we were. On Resurrection weekend. A group of strangers, getting acquainted through the simple and common act of sharing food and remembrance. Some of those present were passionate cooks. Others were just developing their culinary courage. At least one, admitted she was not a cook at all, but she did really love to eat. Whatever the motivation, we all had at least one thing in common — our hope that this, the first in a series of Apron Strings Community Conversations, would restore cooking to its rightful place as the center of family and home, while taking down barriers and building up community one person at a time. And, simultaneously, black cooks would be re-born.

Renatta is an artist and a self-proclaimed “preserver of tradition” determined to keep memories of gardening, crabbing and cooking with family alive. She took a seat at our long table of sisterhood alongside Tahila, Luanne, Razz, Linda, and three generations of women from Lily Grove Missionary Baptist Church, who not only came to join the conversation, but agreed to be part of our oral history project with the University of Houston and Foodways Texas, which will collect stories and recipes of Texas women.

Crystal Granger, the center of the generations and an architect, described how she learned to appreciate the precision and science of cooking from her grandmother who practiced a particular kind of mise en place. The artsy side of her culinary skill, she explained, comes from her mother, Shirley. Shirley, a former teacher, now spends her days motivating seniors toward active living, employing some of the same strategies that once helped her inspire youngsters to learn. As she regaled us with her special way of coaxing reluctant seniors out of the withdrawl that can come with aging, her mastery of culinary art as an educational tool that can nurture became evident. With Crystal, Shirley, and Aunt Marva Smith as role models, it’s no wonder grand-daughter Chimere has such incredible passion for baking and a joy for living.

This coming weekend, the Granger family will be interviewed by students from the University of Houston’s Department of History. They will talk about their tea cake chronicles and the important life-skills they developed while cooking and baking together. The goal of the project is to break the Jemima Code by creating a permanent record that documents and preserves African-American culinary truth for future generations of individuals and researchers, too.

Paradoxically, if someone had bothered to interview the Turbanned Mistress and capture her testimony she would certainly have communicated a few simple anecdotes about life during slavery, but like parables, her experiential yarns would likely have revealed her secrets of emotional and physical survival under barbaric circumstances, too. And that translates into useful lessons about perseverance and discipline, tolerance and self-worth.

Linda Shearer, director of PRH put the whole process in perspective — comparing our Easter gift with the narrative artistry of John Biggers and the way he used cultural heritage and everyday experiences to change the perception of African Americans.

“Your life can be your art,” Shearer said, as the afternoon drew to a close and we all basked in the glow of new relationships defined by a shared intimacy. “We all have a creative side, but it can take a wide variety of shapes and form. What goes on here is you learn from each other.”

* * *

If you would like to join our conversation and give new life to the subject of African-American foodways, the next Apron Strings kitchen table conversation will take place at Hearth House, at Project Row Houses (projectrowhouses.org) in Houston on May 21.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | May 5, 2010 | Kitchen Tales

Spending the week preparing for my talk on Southern culinary traditions at the Austin Museum of Art this week led me to a comparison of iconic dishes in cookbooks written by black and white authors. The difference? Not much. Not that I was surprised. For years Southern food expert and cooking teacher Nathalie Dupree and I pondered the art and soul of Southern cooking. Our judicious conversations involved unresolved exchanges over thorny topics like boundaries and ownership — a classic study in “my dog’s bigger than your dog.”

If we were having that conversation today it would be muddied by African American authors coming to print with topics that don’t conform to the putative soul food paradigm. Add to that the sheer number of books written about the Southern food “experience” and its no wonder the gap between black and white culinary experiences has narrowed. Finally.

Things weren’t always this way. Southern food is perhaps America’s earliest example of “fusion” cooking, influenced by the rainbow of French, Spanish, West Indian, Dutch, German, Chinese and African traditions that seasoned its pots. It is comprised of iconic dishes such as crisp fried chicken, delicate biscuits, crusty cornbread, barbecue, Hoppin’ John, greens and grits. And, it was born in poverty. The cultural quagmire ensued when cooks, both white and black, tried to shed this humble image.

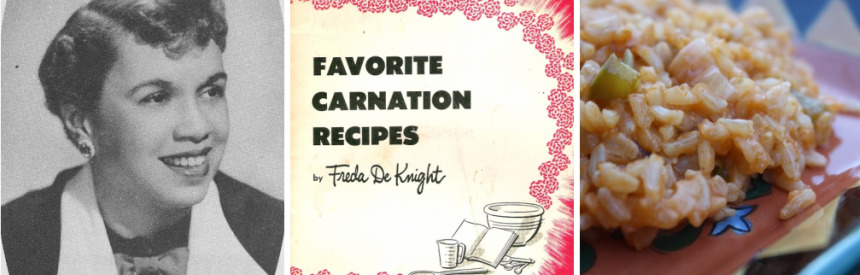

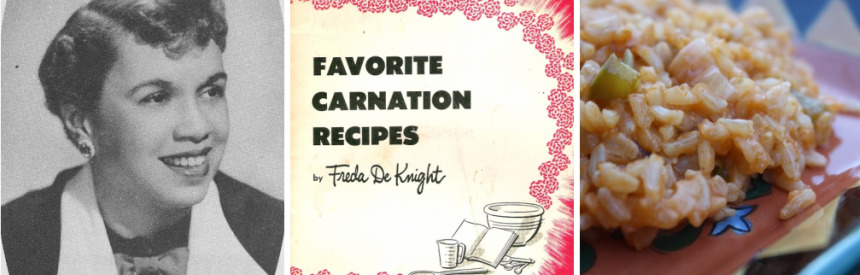

One of the first women to advocate for African American culinary dignity and ownership was Freda De Knight. She is my hero.

As a recipe developer for food manufacturers, and food editor for Ebony Magazine, De Knight understood the work of the kitchen, and she was familiar with the publishing scene when she undertook the first retelling of black cooks’ lives from a culinary point of view in her 1948 recipe book, A Date with a Dish. (Date was revised and reprinted as The Ebony Cookbook, in 1962. Several years later, the Carnation Company tapped De Knight to pen a booklet of “Favorite Carnation Recipes” using evaporated milk.)

With the help of a device she called the Little Brown Chef, De Knight asserted great confidence in her ancestors’ creative accomplishments, their “natural ingenuity” and love of good food. She elevated the tricks of “old school cookery” in a way no one before had tried – beyond the limits of poverty food. She wrote:

It is a fallacy, long disproved, that Negro cooks, chefs, caterers and homemakers can adapt themselves only to the standard Southern dishes, such as fried chicken, greens, corn pone and hot breads. Like other Americans living in various sections of the country they have naturally shown a desire to become versatile in the preparation of any dish, whether it is Spanish, Italian, French, Balinese or East Indian in origin.

De Knight obviously recognized that a well-organized compilation of explicit recipes would have staying power and attract a wide audience. In more than 400 pages, she offered something new– entirely new at least as far as black cookery was concerned – to the cookbook buying public: The secrets of proficient African American cooks, in a “non-regional cook book that contained recipes, menus, and cooking hints from and by Negroes all over America.”

De Knight built a strong case for the versatility and adeptness of African American cooks by expanding classic cookbook sections on household hints and cooking tips. She suggested colorful vegetable plate combinations for holidays and spring menus. Gave clear and concise directions for humane preparation of live lobsters. Recommended methods of preparing and serving new food varieties. And, she infused her technical instructions with entertaining vignettes, which she collected while traveling from South Carolina to Michigan to conduct interviews and gather recipes from black chefs, renowned caterers, celebrities, and everyday home cooks. It is a cruel irony that the delightful tales in her “Collectors’ Corner” galvanize the mission to honor invisible African American expertise, but they were omitted from later editions. If you can get your hands on the 1948 edition, snap it up. Meanwhile, enjoy this little sample:

My father died when I was two and because my mother was a traveling nurse, I was sent to live with the Paul Scotts in Mitchell, South Dakota. The Scotts were famous at that time as being the finest caterers in the middle west and among the finest in the country. They had their own farm and raised most of their own products. They raised chickens, made their dairy products, did most of their canning and had the traditional country smokehouse for their own meats. the made the first Potato Chips for retail sale in that part of the country.

“The Scotts were the inspiration for my early cooking aspirations which gave me every opportunity to absorb all of their fine recipes and rudiments of cooking, preparing food, and catering. Although Mama Scott’s education was limited, she could measure and estimate to perfection without any modern aids, and her sense of taste, her ability to create was phenomenal…

Because of De Knight we can see how an old school cook might have been unable to tell you whether three pinches of salt was equivalent to a half-teaspoon, but she knew whether it was enough to season your cornbread. As a result, she imparted more tips, more insight, and more wisdom at a time when modern kitchen conveniences and TV dinners minimized a housewife’s encounters with food, and threatened to turn mealtime into a brief, impersonal experience. De Knight’s self-assured truisms uplifted cooks:

Cooking is not a problem,” she said. “It’s just knowing how and mastering the little tricks of the profession with ‘thought’.

Who is your kitchen hero?

In Her Kitchen

Freda’s Spanish Rice

Ingredients

- 3 tablespoons butter, bacon drippings or oil

- 1/2 cup chopped onion

- 1/3 cup chopped green pepper

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 tablespoon chopped celery

- 1 cup whole grain brown rice

- 3 cups boiling water

- 1/3 cup tomato sauce or 3 tablespoons tomato paste

- 1 teaspoon salt

Instructions

- Heat oil in a heavy skillet. Saute onion, pepper, garlic and celery until tender. Do not brown. Stir in rice, stirring until well mixed and rice is lightly browned. Add water, tomato sauce and salt. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat and cook over very low heat, covered, until rice is light and fluffy. Stir lightly with a fork before serving. Grains should be whole and firm.

Number of servings: 6

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 20, 2010 | Kitchen Tales

Our pie-baking excursion had barely begun, and already I was getting a little teary-eyed subconsciously drifting between wondering what life would be like for these kids when they returned to their homes, and teaching them a few basic cooking skills.

“Wash your hands and your produce. Gather your ingredients and read your recipe from beginning to end.”

…Is there someone there to whisper words of comfort in their ears when they are sad or terrified? Do they have anyone to tell their dreams to?

“First you grip the apple with your index finger and your thumb”

…Have they ever been given advice over a steamy hot cup of cocoa with marshmallows on top?

“Take hold of the knife in your other hand and apply gentle pressure to separate the skin from the flesh.”

…Where do they go for advice?

“Yes, we could use a vegetable peeler, but then you don’t learn the proper way to handle a knife. If you don’t hold the apple correctly, the task takes longer and is much more difficult.”

…Why are they so hurt and angry?

“Be patient; the pie will be out of the oven soon.”

…What can I do to help preserve their dignity?”

I try to settle my thoughts down and accept the reality that this little group of troubled high schoolers and I have come together at The Kitchen Space to celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King’s message of opportunity and equality, and to bake an apple pie — not bring about world peace. On second thought, maybe we could…

Tears well up in my eyes as we talk about slavery and civil rights, and the role education plays in the pursuit of freedom. They tell me about the role models in their community and I get them thinking about the ways food careers are linked with independence, notoriety, and prosperity. They giggle and chat incessantly as they eagerly wait for their pies to emerge from the oven — expressing a new-found confidence and pride in their work and showing respect for the commercial kitchen by cleaning their tools and their workspace, all while patiently anticipating the pleasure of the first bite of a simple, sweet treat that they made themselves.

They wrap their warm pies in foil. Head toward the Travis County van that gives them a second chance. Then one of the boys breaks through the tough-guy persona he had projected just 90 minutes earlier by expressing his appreciation for our time together.

And he gives me a hug.

This risky, tender-hearted gesture captures the very essence of the SANDE Youth Project, the nonprofit mentoring and training program I founded to inspire and empower underserved youngsters toward healthy, productive futures. It also personifies the vision of last week’s MLK Day Dream Pie Social for fellowship and unity:

“A pie is a warm hug wrapped in a crust.”

What’s your pie story? To share your favorite pie memory, click below on COMMENT.

If you would like to learn more about The SANDE Youth Project visit my website at:

www.tonitiptonmartin.com or

Edible Austin

To learn more about the MLK Day Dream Pie Social, visit:

www.serveadream.org or

The Austin Chronicle or

www.kvue.com or

The Austin American Statesman

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 13, 2010 | Kitchen Tales

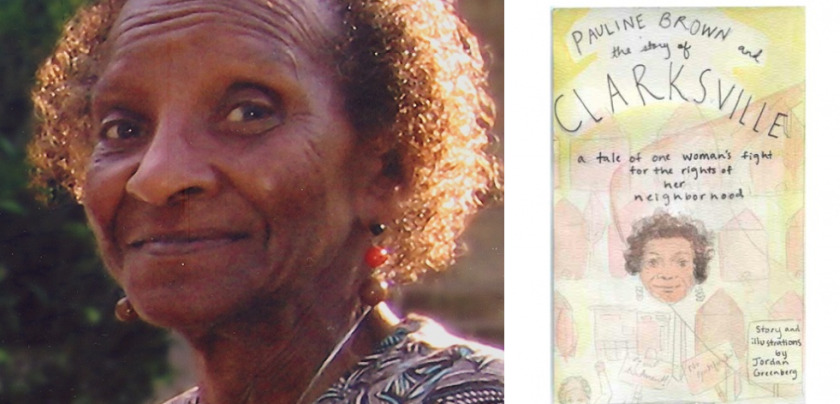

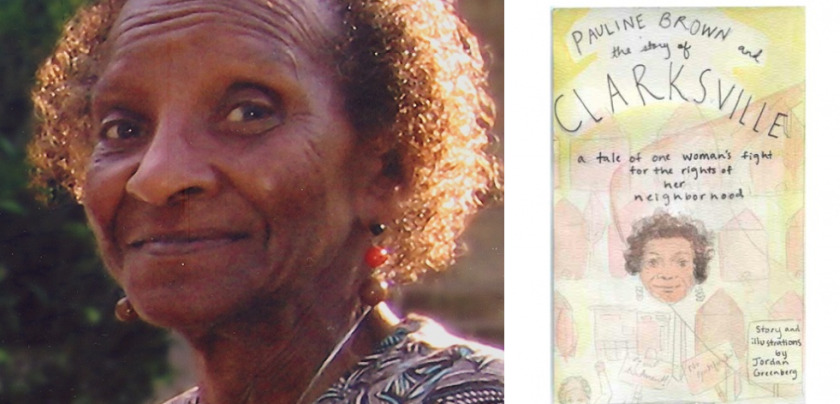

Pauline Brown wasn’t the kind of woman to let segregation bring her down. “I have my share of memories, some of them exciting, some of them scary, but I still love every moment and I will fight for Clarksville until the day I die. This is my area; our home.”

In a somber voice that mobilizes with gripping tales of growing up black in a segregated quarter of Austin, without street lights or indoor plumbing, she reflects on the importance of preserving community. In another interview, the topic turns light-hearted. “I made the richest lemon pie in Clarksville or anyplace else.” Virtually every story she told bewitched with a spirit of unity, and the hope for a brighter future.

I never met Pauline Brown; I got to know her because of the impression she left on a young high school student named Jordan Greenberg, and on the entire neighborhood of Clarksville, a town founded by the former slaves of Texas Govenor Elisha M. Pease.

Pauline Brown’s story-telling at the Austin Batcave, a nonprofit writing center for kids, captivated Jordan. “I was really struck by her words and felt that the stories and memories she told were beautiful. I thought a lot about her and what she said long after the interview was over, and even more so after I read about her passing (away) just a few weeks later.”

Jordan was so certain that Pauline’s “amazing accomplishments” would connect with children, that she decided to write and illustrate a scholarship-winning book about Pauline’s efforts to save historic Clarksville from urban sprawl. The little book is a tender-hearted reflection on the lives former slaves scraped together. It is also an ode to the wisdom that kept bitterness at bay.

The “ville” of Pauline’s youth is gone. Precious few of its tin-roofed, shot-gun styled homes still dot the wooded and hilly landscape. They have been replaced by a global village and modern, suburban architecture. But, her insights and ambitions linger like the sweet aroma of fresh-baked pie:

“Never forget where you come from.”

“These are great times, please use [them] wisely.”

“Love yourselves.”

“Thank your mother and father, or whoever is taking care of you.”

“Do your part; help wherever you can.”

“Please stay in school.”

“And, remember: this is Clarksville the first freedom town west of the Mississippi, founded in 1871.”

*

Pauline Brown’s memory will be honored this weekend in Austin at the Second Annual Dream Pie Social at Sweet Home Missionary Baptist Church in Clarksville, one of four old-fashioned community gatherings planned to uplift the community in celebration of the Martin Luther King Jr., Holiday. I joined the ServeaDream Organizing Committee, because a pie social encourages citizens of every stripe to come together, and savor food and memories while raising money to preserve the community — even though I admit that being so close to the disregarded family homes and accomplishments has made me a little weary.

Thank goodness for new friends and the precious lore of strong, affirming women like Pauline Brown.

Jordan sums it this way:

“Pauline’s story is proof of the adage that ‘one person can make a difference.’ She was a leader in her community who was truly effective and was also a warm and loving person. Pauline is everything a person can hope for in a role model or heroine; she was brave and determined and also compassionate and kind. She was a strong leader in the community but also a gentle and loving participant… I am very grateful that I have been able to directly give back to the community I was so inspired by.”

Who inspires you?

If you would like to know more about Austin’s Dream Pie Socials, please visit: www.serveadream.org

In Her Kitchen

Lemon Meringue Pie

Ingredients

- 1 1/2 cups water

- 1/3 cup cornstarch

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 cup cold water

- 1 3/4 cups granulated sugar

- 3 eggs, separated

- 2 tablespoons butter

- 1 tablespoon grated lemon zest

- 1/2 cup freshly-squeezed lemon juice

- 1 baked (9-inch) pie shell

- 1/4 teaspoon cream of tartar

- 1/4 teaspoon lemon extract

Instructions

- Bring 1 1/2 cups water to a boil. Dissolve the cornstarch and salt in the cold water. Add to the boiling water, stirring with a wire whisk. Allow to cook until thickened, about 5 minutes. Add 1 1/4 cups of granulated sugar and bring to a boil, then remove from the heat. In a small bowl, beat the egg yolks. Beat a little of the hot liquid into the yolks, then add the yolk mixture to the hot mixture. Stir in the butter. Return to th heat and cook over low heat, stirring constantly, until the filliing boils. Cook 1 to 2 minutes, then remove from the heat. Add the lemon zest and juice and beat with a wire whisk to cool slightly. Set aside 30 minutes. Pour into the pie shell and let cool. Preheat the oven to 400 degrees. Beat the cream of tartar with the egg whites until frothy, then beat until soft peaks form. Gradually beat in the remaining 1/2 cup sugar and the lemon extract, and continue to beat until stiff peaks form, about 2 minutes. Spread the meringue onto the cooled lemon filling, spreading to the edge of the crust to seal. Bake until firm and golden, about 6 to 8 minutes. Allow to cool on a rack to room temperature, then refrigerate at least 3 to 4 hours before serving.

Note: Topping the cooled filling with the meringue will prevent weeping.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Dec 30, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

So we went to a cocktail party last night to celebrate the coming of the New Year and the inevitable question came up.

“What do you do?”

I explain that I have just started blogging about the history of African American cooks, and before I can finish my sentence, a woman who looked like she would know better, glared over her glass of Tempranillo and asked, “Why are you still worrying about what happened 200 years ago? It’s in the past; get over it.”

“Well, I can’t get over it,” I scold her. “Neither should you.”

Here’s why:

In 2002, Texas A&M University’s student newspaper, The Battalion, published a political cartoon, which resembled the kind of degrading Jim Crow-era imagery that appeared routinely on manufacturer’s labels, in advertising, magazines, and Southern daily newspapers. Only worse.

The illustration depicted a large black woman wearing an apron, holding a spatula, and chastising her son at TAKS Test time. The Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills exams (TAKS) are serious business for politicians, school districts, and parents in the Lone Star State, and evidently black boys performed pretty poorly that year. Neither the student, nor his or her editor, nor the journalism advisor questioned the suitability of using a bigoted turn-of-the-century image to portray a modern-day mother’s concern for her son’s poor academic performance. I did.

I’d like to agree with the faculty who defended the student’s actions as “an unfortunate mistake” and the woman at the party, who believe that in these “post-racial times” our society does value diversity, abhors “pulling the race card,” and promotes “no color-line” policies, but how can I? The A&M cartoon says that even with re-doubled efforts, our high-technology children cannot see beyond the narrow Aunt Jemima cliché. How can they?

Everywhere you look, the image of African American mothers is stuck in 1900.

Media credentials legitimize journalistic lapses, such as this. Radio disc jockeys like John “Sly” Sylvester” and Don Imus get a pass. Black men in rank drag acts, including Eddie Murphy as Norbit and Tyler Perry as Madea are modern-day re-creations of bigoted minstrelsy and Negro impersonation. And don’t even get me started about the Pine Sol Lady and Lisa from the “Get Mommed” Kleenex ad. It’s as if there was a sign on the casting call door that reads: “Only big girls need apply.”

Please don’t get it twisted; this is not a slam against plus-sized women. What I’m saying is that in the absence of a written history to defy – or at least counter-balance the stereotype – the picture of every African American woman in our national minds’ eye resembles a rude trademark. That shallow image ignored the powerful love language of mother’s kitchen, and even worse, cataloged her skill and virtues as anything but extraordinary in a file marked “idiot savant.”

To be a patient and loving wife and mother; to be smart, talented, hard-working, physically and emotionally strong, yet compassionate; to multi-task: these are the characteristics that intersect in the black women who fed this nation, but they are lost in lampoon.

Which makes two things clear to me: In the year 2010, we need a new picture to replace the Aunt Jemima asymmetry. And, adults like those at A&M who still think that it is appropriate to classify stereotyped imagery as satire should not be teaching anybody. At all.

In order to wrap up this heated conversation with my dinner companion, we take one more trip to the Internet. I tell her about a recent Google search of the culinary cliche “slaving in the kitchen.” I name some of the assorted modern convenience foods, gadgets, and equipment that popped up — all designed to save time and effort in the kitchen — including a Japanese knife called the “kitchen slave,” which offers “simplicity, utilitarian attitude, and beautiful elegance.” Then I contend that the Jemima Code is a uselful, new tool with a similar twist on the theme.

I say that as we enter the season of new priorities and make resolutions to begin this or quit that, we should use this journal to cut through historical rhetoric and expose the wisdom and of poetry of African American culinary artists, to bring their skill and professional excellence into the light.

At last, she relents; the conversation moves on.

So why did I call it the Jemima Code?

Merriam-Webster defines a code as “a body of laws systematically arranged for easy reference; especially one given statutory force; a system of principles or rules (as in moral code); a system of signals or symbols for communication used to represent assigned and often secret meanings.”

To decode, the dictionary goes on to say, is “to convert a coded message into intelligible form; to recognize and interpret a signal; or to discover the underlying meaning of.”

As Americans, we live with all sorts of standardizing codes – dress codes, moral codes, codes of conduct, codes of law, bar codes. Recipes are codes. So are prescriptions. But when we talk about a “Jemima Code,” we see how arrangement of words and images synchronized to classify the character and life’s work of our nation’s black cooks into an insignificant symbol contrived to communicate a powerful double message, based upon exaggerated principles and secret meaning.

Like most codes, the Jemima Code is a 200-year-old system of prejudices and double standards that originated in the hand-written journals and ledgers of slaveholding women and their letters to family and friends. Their inconsistent, emotional observations bloated the image of female house servants. Opinions about those unrealistic behaviors established character types, and those stereotypes transmitted unwritten messages about black cooks that were open to interpretation.

The result was an image America used as powerful shorthand. Aunt Jemima became the embodiment of our deepest antipathy for and obsession with the women who fed us with grace and skill. In short, a sham.

Ironically, the same observations that created this code can break it; the difference is interpretation.

I don’t believe that gratitude for years of servitude, claiming an absolute, single historical truth about black cooks, or redefining culinary processes with black sensibilities will instantaneously remove the haze of hard labor that obscures the real wisdom of their work — a haze that still lingers over modern kitchens. Truth will.

Historian and scholar Sidney Mintz, speaking several years ago at a dinner in Washington, D.C., impelled the idea for this work when he encouraged the audience to find new ways to exalt America’s unsung heroes of the kitchen – the African American cooks.

He said: “We need to honor those women, not only for their achievements as cooks, but also for the terrible burden they bore, standing as they did at the very crossroads where the idle free and the oppressed unfree were joined – in the kitchen. As we do them honor, we have to imagine the restraint, patience, and intelligence they themselves had to possess in order to go home each night to their own families, their men and their children, having lived through another day in the skilled but un-rewarded service of others in whose power they were.”

To ignore these virtues is like eating fried chicken without the skin: You just know something is missing.

Have some…

In Her Kitchen

Pan-Fried Chicken

Ingredients

- 1 (4-pound) frying chicken, cut up

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- 3/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 teaspoon black pepper

- 1/4 teaspoon garlic powder

- 1/4 teaspoon paprika

- Oil

Instructions

Rinse chicken pieces and pat dry. Place flour, salt, pepper and garlic powder in a small paper bag. Add chicken pieces and shake to coat evenly. Let stand 10 minutes. Heat 3/4- to 1-inch oil in a 9 or 10-inch cast iron skillet to about 375 degrees. Add chicken in batches and cook until chicken is crisp and golden brown, about 10 minutes per side. Do not crowd pan. Drain chicken on paper towels. Serve warm.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

Comments