by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 14, 2010 | Uncategorized

I had already imagined the delicacies and grace that would be rendered by Eliza’s Cook Book: Favorite Recipes Compiled by Negro Culinary Art Club of Los Angeles long before I ever bid my way to a rare and highly-coveted copy. I can tell you this sophisticated gem of some 100 pages is a miraculous find and a lovely example of African American flair in the ever-present asymmetry of the Jemima cliché. It shows that there was another side to black female cooks – a side with class.

Eliza was organized by Beatrice Hightower Cates and published at a time when national pursuits – from board games and radio to mystery novels by Agatha Christie – helped Americans escape the rigors of Depression-era living, while field writers for the Federal Writer’s Project, a part of the Works Progress Administration, recorded the life stories and oral histories of former slaves.

Amidst all the resources women had for scientific cooking and healthful meal planning the members of the Culinary Art Club obviously noticed a void. Cooking is indeed a science, but it is also an art – one that requires special attention, whether the cook is occupied with a simple method like brewing coffee or a more elaborate project, such as making a velvety sauce. Cates and the members of her club clearly knew the pleasures of fine cooking and took pride in their extensive catalog of “ladies’ luncheon” and light dinner dishes.

The recipes were decidedly upscale. To acknowledge the cultural tradition of hospitality and enrichment, Eliza was “Dedicated to the mothers of the members of the Culinary Art Club,” women who probably descended from slaves. And yet, I couldn’t help but notice once again how few historically Southern recipes are here. At first glance this practice seems disingenuous, but I don’t think it is as simple as that.

Eliza’s liberated cooks probably had unlimited access to finer cuts of meat and better quality vegetables, enabling them to extend their repertoire beyond biscuits, cornbreads, and croquettes. At least that’s what is reflected in the recipes they selected for their cookbook. Dishes range from assorted canapes, to creamy bisques and soups, saucy fish and lobster concoctions, all manner of meat and game (including steaks, roasts, and casseroles), vegetable sides from A to Z, and dozens of rich breads and sweets.

Neither cabin methodology nor the haze of hard labor that hovered over black kitchens appears to restrict their creativity. They didn’t let the yolk of tough economic times, lack of information, or even minimal cooking skills stifle them. Nor should we.

Times like these call for a return to the kitchen, and these women prove to us that trip doesn’t have to be laborious or difficult. Just get out a simple, but classic recipe and practice, practice, practice. When it’s time to serve your masterpiece, remember two the things the Culinary Art Club teach us: Exceptional cooks aren’t born, they are made; and attitude is everything.

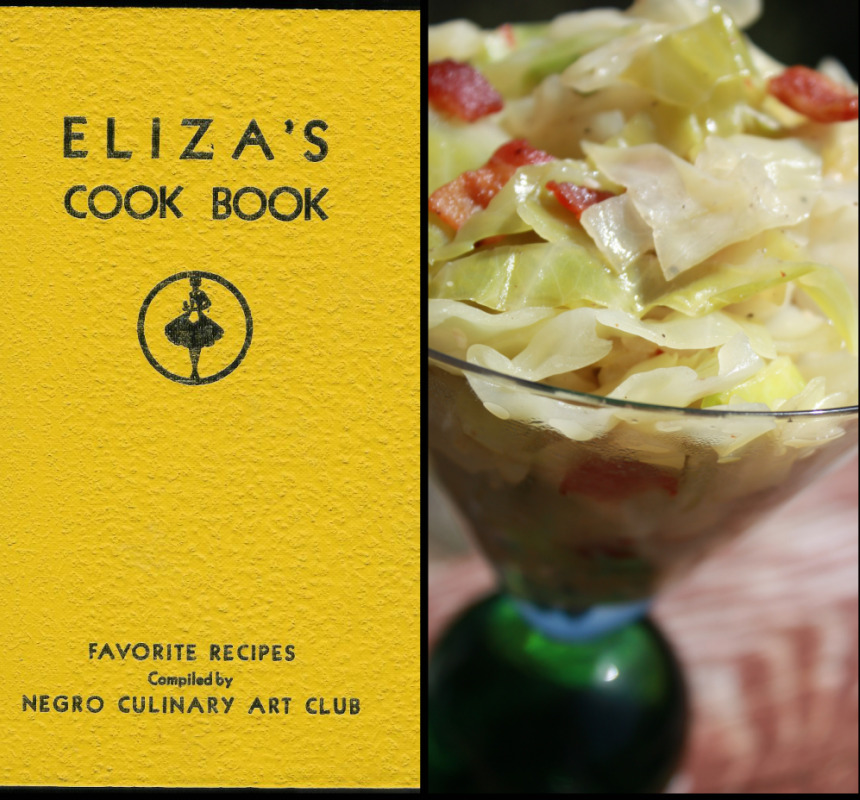

Even a homespun recipe like smothered cabbage can be made extra special, as Cates recommends. She simply layers shredded cabbage in a casserole with tomatoes, bacon, onions and green pepper, then crowns the dish with a dusting of Parmesan cheese before baking.

This basic cabbage saute should help get your imagination started.

In Her Kitchen

Sauteed Cabbage with Bacon

Ingredients

- 6 slices bacon, cut into pieces

- 1 medium onion, diced

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 small head cabbage, thinly-sliced

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon black pepper

Instructions

- Saute bacon in a hot skillet with a tight-fitting lid, until almost done. Add onion and cook until onion is translucent. Stir in garlic and cabbage and cook 3 to 5 minutes, stirring occasionally to prevent sticking. Cover skillet and reduce heat to low. Steam cabbage to desired doneness, 15 minutes for tender-crisp, 30 minutes for completely wilted. Season with salt and pepper before serving.

Number of servings: 6

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Feb 17, 2010 | Plantation Cooks

A month into my study of black women cooking in America’s kitchens and already I can see numerous professional characteristics displayed by slave women. Plantation cooks worked under pressure and still devoted attention to detail. Fashioned a creative style under stone-age conditions from meager ingredients. Possessed exceptional organizational skills.

But, it was their forebearing management style that caught my attention this week, following popular British chef Jaime Oliver’s TED challenge that Americans take back responsibility for educating their children about food. If Oliver’s plans to join the Obamas and others in the fight against obesity and food ignorance seems intrusive, it shouldn’t; we live in an era when many adults become completely depressed by the thought of kids in the kitchen.

Not these women. They supervised a gaggle of helpers, some of them young children, without surrendering their hearts to despair just because of the distraction and hazard of children underfoot.

We all know that slavery’s children were exposed to heavy labor at an early age. From Works Progress Administration interviews, we also learn about the skills and traditions their mothers handed down to them as they worked side by side, which reveals a communal spirit, not weakness.

Imagine Mammy or Aunt Chloe redirecting her feelings, telling herself and her children they were allowed “to “play” in her kitchen or to “help out” with the cooking. At the same time, in an informal way, she taught them basic responsibilities, transferred culinary expertise, and instilled confidence and self-esteem, when she allowed the child to accomplish simple tasks like helping her to put on a pot of rice.

Aunt Mary Graham remembered that Mammy Rose, the cook managed the fireplace and several servants at once, including children on her Washington, Louisiana plantation. Aunt Mary was the “table gal,” who learned from the Missus how to “make it fitten fo’ fine folks ter eat at.”

A small girl, usually the cook’s daughter, carried the food to a small table near the kitchen door, then the table gal would carry the meal into the dining room. Mammy Rose, she said, “Didn ‘low no boys ter wait on tables caise dy rush roun’ so fas’ an’ spill things.”

Mandy Morrow, a former Texas slave who cooked in the Governor’s Mansion, was one also of those early trainees. She recalled carrying food pails to the field, managing the smoke in the smokehouse, making preserves, and “making sorghum molasses every year to sweeten the coffee.”

Aunt Charity Anderson, one of six house servants, explains: “My job was lookin’atter de corner table whar nothin’but de desserts set.”

I have to admit that some nights, these narratives troubled my sleep, but most times, I tried to put on my own mother apron and think about the joy I share with my children at the table. And that brought memories of my son Brandon’s Chocolate Chip Cookies to mind. His recipe is a family favorite that grew out of a challenge when he was in middle school and I was a newspaper food editor. He taunted me into a weekend cookie bake-off, which he proceeded to win with this simple, sweet recipe. I make them with the kids in my cooking classes and we still laugh about it today.

What recipe did your mother use to bring you into the kitchen?

In Her Kitchen

Chocolate Chip Cookies

Ingredients

- ½ cup margarine

- ½ cup shortening

- ¾ cup brown sugar, firmly packed

- ½ cup sugar

- 1 ½ teaspoons vanilla

- 1 egg

- 1 ¾ cup all-purpose flour

- 1 teaspoon baking soda

- ½ teaspoon salt

- 1 cup semi-sweet chocolate chips

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 350 degrees. In a large bowl, stir together margarine and shortening until mixed and light yellow. Add sugars and stir until creamy. Stir in vanilla and egg. Stir in flour, soda and salt. Blend well. Stir in chocolate chips and mix well. Wrap in plastic and shape into a 12-inch log. Refrigerate until firm. Slice cookies about ¼-inch thick or drop dough by rounded teaspoonfuls, 2 inches apart onto a lightly greased cookie sheet (or spray with non-stick vegetable spray). Bake for 8 to 10 minutes or until light golden brown. Immediately remove cookies from cookie sheet to wire racks and cool.

Number of servings: 48

In Her Kitchen

Comments