by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 13, 2012 | Community Cooks

Yesterday morning, just before we went on the air to invite everyone, everywhere to honor the Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday by serving “Peace Pie,” my friend and partner Luanne Stovall revealed to the staff and guests at KAZI radio in Northeast Austin the warm, golden-brown, homemade apple pie she had tucked inside a shallow Steve Madden shoe box. Mouths were watering. By the end of our time with Dora Robinson on the Soul Vibrations show, eyes were watering, too.

Our movement to establish a food tradition that honors the legacy of Dr. King and his passion to build the “Beloved Community” unifies in greater ways than other holiday food traditions like Thanksgiving turkey, Christmas cookies, Valentine chocolates and Easter ham. And, it has begun catching on in cities across the nation — from Austin, New York, Chicago, Houston, and Cleveland, to Seattle and Utah.

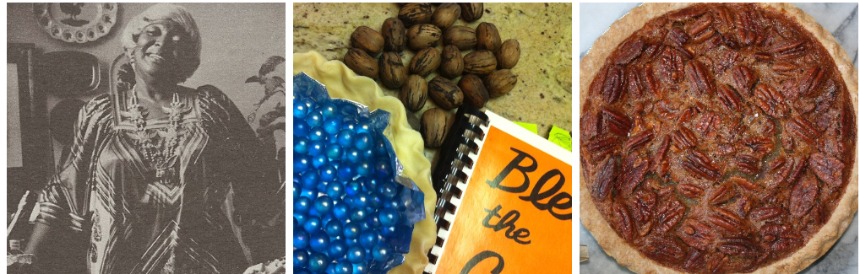

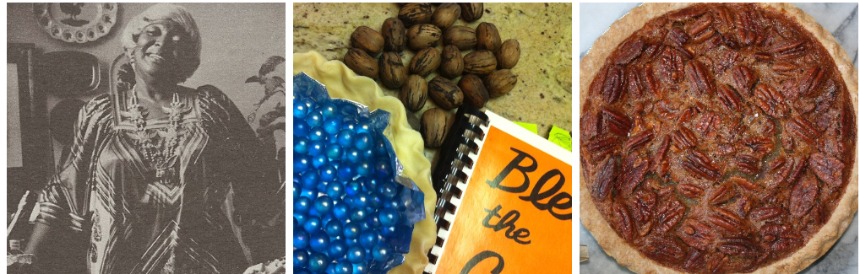

Maybe it is because Peace Through Pie socials are inspired by the Jemima Code women who for generations brought people together at the table to solve problems, salve wounds, and uplift communities. From their pulpits at the kitchen table, African-American women practiced servant leadership. As agents of reconciliation, they quietly and subtly brought people of diverse backgrounds together at the table in southern homes and restaurants to enjoy their good cooking. But unlike the fictional women of the bestselling book and film “The Help,” who served poop-laced pie with the intent to harm, Jemima Code women baked and served pies filled with love. These role models encourage Americans to serve pie with the intention of cultivating peace and harmony at the table by making room for all and respecting every voice.

Cookbook author, caterer and community servant Bessie Munson is one of those remarkable women. Munson was raised on her grandparents’ farm near Bartlett, Texas, where the food was always plentiful and sumptuous, she says in her 1978 cookbook, Bless the Cook. She taught cooking classes in Arlington and wrote fondly of the memory of festive and wonderful gatherings around the family table… and of all the “bountiful and beautiful meals that became the reflection of a happy outgoing lifestyle in which anything can be achieved when you share and reach out to others.” In her book, she illustrates the proper way to crimp pie crust to make the edges beautiful, along with several pie recipes, including one for perfect crust.

Why reach out with pie? For three reasons: You don’t have to be a great cook or spend all day in the kitchen preparing an entire meal; Pie is universal, symbolizing inclusiveness with its round shape and diverse ingredients — whether sweet or savory, sugar-free, or gluten-free. It comes in many shapes and sizes from around the world — Latin empanadas, Indian samosas, Italian calzones and pizza pies, Jamaican and Ethiopian meat pies, British and Aussie pies, Greek spinach pie, even Asian dumplings. Finally, “Peace Pie” provides nourishment for heart and soul, creating Beloved Community and enacting Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s message of hope, equality and social justice with a food he reportedly really enjoyed (simple recipes are everywhere on the web and on the back of the bottle of Karo Syrup).

On Jan. 18, 1986, when President Ronald Reagan signed Proclamation 5431 establishing the first MLK Day, he encouraged “…all Americans of every race and creed and color to work together to build in this blessed land a shining city of brotherhood, justice, and harmony. This is the monument Dr. King would have wanted most of all.”

As I left the station, I reflected on the conversation about Peace Through Pie and the multiple ways that sharing a piece of fresh-baked Peace Pie with a family member, friend or neighbor is an enduring recipe for an edible monument. It reminds us year after year to follow Munson’s lead by reaching out to others. This weekend, as you put down social and political weapons and break down generational, race and gender differences to honor Dr. King, why not gather the ingredients for your own edible monument, craft them with your heart and hands, and share with a friend.

To learn more about hosting a Peace Through Pie social or to see a listing of Peace Through Pie Socials in your community, visit www.peacethroughpie.org.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 28, 2010 | Community Cooks

What do you do to become a better cook? Consult an expert, of course. That is exactly what readers did in 1930’s Maryland when The Baltimore Sun published Aunt Priscilla’s Recipes, a regular recipe column of conversational culinary advice.

The writings followed a common style for the time. Every day, Aunt Priscilla answered reader requests. Every day a recipe followed a brief statement of culinary wisdom with dishes that were sweet and savory, simple and complex. Some days, she offered ideas for variations; other days she shared make-ahead secrets. But always she spoke in pernicious slave dialect. A Jemima-like illustration accompanied her words.

“I’se bery glad to gib you de crab recipes Miss Katie, speshully as serbil mo’ ladies done ast fo’ de same. Try yo’ crab cakes dis way.”

Odd communication for a black woman so intelligent that a major metropolitan newspaper featured her recipes, right? It becomes even more so as the truth about Aunt Priscilla unfolds.

Discovering Aunt Priscilla several years ago was the highlight of my search for evidence of real black cooks in the archives of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive at the William L. Clements Library on the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor. It was there that I encountered her perky little cookbook, Aunt Priscilla in the Kitchen, A collection of winter-time recipes, seasonable menus and suggestions for afternoon teas and special holiday parties, authored “By Aunt Priscilla, herself.” The tidy collection represented a stunning departure from the publishing traditions of previous generations, ushering in a new way to cloak black women’s kitchen skill. (Some time later I added a couple dozen Aunt Priscilla newspaper clippings to my collection.)

The years following the publication of the influential The Boston Cooking School Cookbook, by Fannie Merritt Farmer, were chaotic for cooks. In the North, the domestic scientists classified and codified cooking, while their contemporaries in the South elevated their culinary proficiency by lifting up local specialties, and the pleasures of regional soil — the taste of terroir as we know it today. The Southern belles also published collections comprised of recipes accumulated from “our famed cooks.”

This struggle to define and defend southern regional cooking paradoxically turned the spotlight on black culinary prowess, as prolific Southern authors got caught up in the Antebellum nostalgia sweeping the South. In the introduction to her comprehensive 1927 compilation, Mammy’s Cook Book, Katherin Bell, provides a snapshot of the formula.

“With the dying out of the black mammies of the South, much of the good and beautiful has gone out of life, and in this little volume I have sought to preserve the memory and the culinary lore of my Mammy, Sallie Miller, who in her day was a famous cook…”

Over on the Atlantic Coast, Harriet Ross Colquitt affirmed the black cook’s talent when she published the Savannah Cook Book in 1933.

“We have had so many requests for receipts for rice dishes, and for shrimp and crab concoctions which are particular to our locality, that I have concentrated on those indigenous to our soil…begging them from housekeepers, and trying to tack our elusive cooks down to some definite idea of what goes into the making of the good dishes they turn out.”

Eleanor Purcell, the white secretary of one of The Sun’s most distinguished writers Frank Kent also was among the compilers extracting the coveted specialities of “colored cooks,” but she took a different tack. It was she who posed as the spurious Aunt Priscilla, and the one who answered reader requests for everything from divinity to chili con carni, according to Alice Furlaud. (Furlaud explains how she came to own a copy of Aunt Priscilla’s Cookbook, and how she plied the true identity of Aunt Priscilla from Baltimore friends in a 2008 NPR story.)

But what does it matter? A lot, I think.

In their complete exasperation from trying to prove the value of their cuisine, Southern housewives documented black culinary skill that has been virtually ignored in modern history.

“Most of these recipes were Mammy’s,” Katharin Bell explains. That means that Sallie Miller was competent in more than 300 recipes, many of which are still Southern standards today. The women of Colquitt’s Savannah community demonstrated excellence as entrepreneurs. “The majority of Savannah housekeepers prefer to buy their sea foods from the negro hucksters who…peddle their wares from door to door,” Colquitt writes. And, mythical Aunt Priscilla was the voice and the face of the first African American newspaper food columnist.

Duncan Hines summarized it this way:

“Many Southern ladies had Negro cooks to help them; and just how much we owe to their skill I have no way of knowing except that almost all of the finest Southern dishes are of their creating or at least bear their special touch and everyone who loves good cookery should thank them from the bottom of their heart.”

*

The following recipe was taken from one of Aunt Priscilla’s many newspaper columns.

Aunt Priscilla’s Crab Cakes

To 1 poun’ ob crab meat take 1/2 a small lofe ob bread, 2/3 ob a cup ob milk (6 tablespoons), 2 eggs, 3/4 ob a teaspoon ob musta’d (dry), 1 tablespoon ob Wooster saus, salt an’ pepper to sute yo’ tas’e an’ a dash ob kyan. Crumble de bread an’ poe ober it de milk, lettin’ it set while you fixes de res’ ob de ‘gred’ents. Beat de eggs lite wid de sesinin’, stir in de crab meat an’ mix all togeder wid de bread. Hab yo’ skillet well greased an’ hot. Make out de cakes an’lay on’y as many as you kin han’le e’sy in yo’ pan at a time. Brown fus on one side, deon on de oder, bein’ keerful not to let ‘em burn.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 20, 2010 | Community Cooks

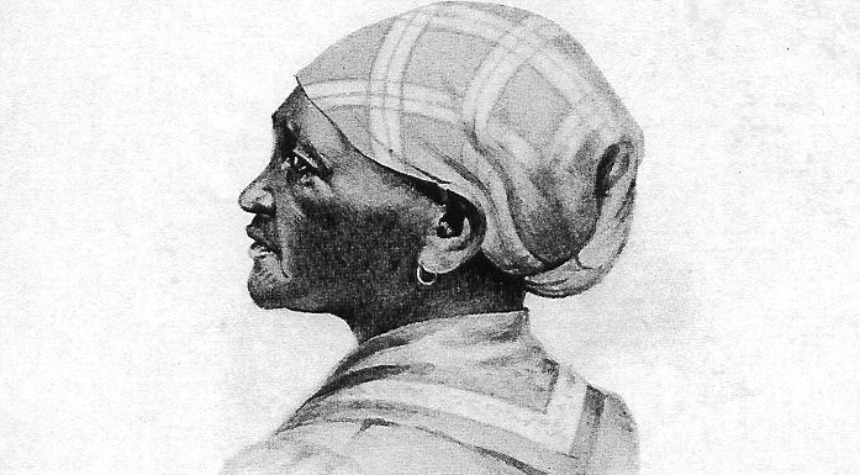

Who is Mrs. W.T. Hayes and why does she matter? The question has baffled me since my friend and Southern sage John Egerton generously gave me her mysterious little recipe book back in the late 1980’s. Now, finally, an answer.

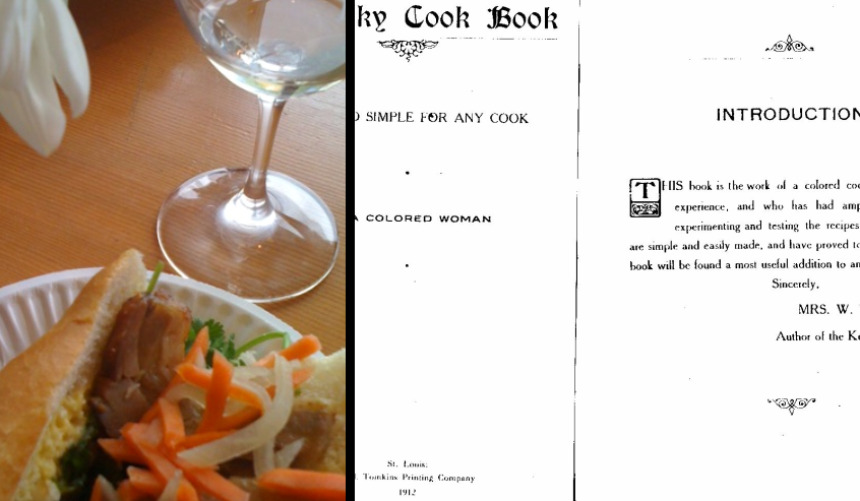

I was beginning my journey as a curious student of African American culinary history; John was the first luncheon speaker I ever heard publicly credit African American cooks for their contributions to the world of cuisine. At the conclusion of a lavish meal featuring southern grilled quail served over his animated and compelling remarks, I leapt from my seat in the posh ballroom of the Ritz-Carlton Buckhead, and bombarded him with questions. In response to my enthusiasm, John rummaged through his brief case and generously gifted me with Mrs. Hayes’ work: The Kentucky Cook book: Easy and Simple for Any Cook, printed in 1912, authored “By A Colored Woman.”

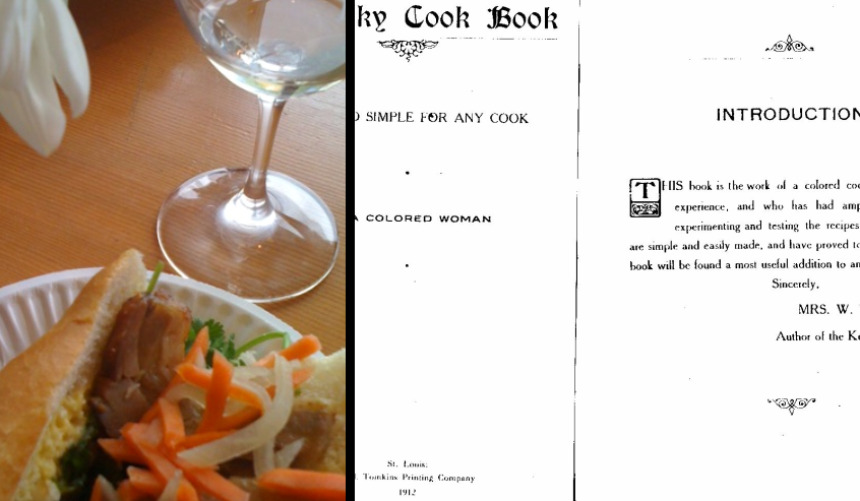

Today I got a huge thrill thinking about Mrs. Hayes again. I’m attending the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP) conference in Portland, Oregon where, for most of the day, I’ve been on a decadent drinking and eating binge in the Willamette Valley. Three wineries poured incredible pinots from their reserve collections, pairing each one perfectly with pork. But the real treat, the part that made Mrs. Hayes come to mind, was lunch at Nick’s Italian Cafe. The menu celebrated pork and Pinot with elegant and light-styled charcuterie, and amazing wines from Eyrie Vineyards. (I could go on and on just about the 2005 Eyrie Pinot Noir pressed from the original, 40-plus-year-old vines brought to the region by David Lett [aka Papa Pinot], but that is another story.)

The chef fascination with pork belly is not news, but the thing I couldn’t help notice was that pork offal was all over the place, on menus, I mean. From a fabulous spicy Vietnamese Bahn Mi sandwich to a decadent Italian pork trippa (tripe) with soft cooked egg and salsa verde, creative expressions of unwanted pig parts ruled the day. Mrs. Hayes had been one of those imaginative and industrious cooks in her day, too, turning sows ears, tails, hoofs, intestines, and private parts into sustaining and delicious dishes. And fortunately her recipes were collected and recorded not as poverty or cabin food, but as signposts of excellence.

I had to know more about this courageous woman who brazenly flaunted her race before the book-buying public, so I took a research trip — coincidentally funded by a grant from the IACP — to the Historical Society in Frankfort, Ky., to look for clues. What I discovered about Mrs. Hayes was better than the discovery of the book itself.

The Kentucky Cook Book was published in St. Louis by the J.H. Tomkins Printing Company, a job printer, which occupied a small room on one floor of a commercial building in Missouri. It contained 45 pages of short recipes composed in the narrative style, and for the most part followed the paragraph form of Mrs. Reese Lillard’s Tennessee Cookbook, which came to print the same year. Strangely, only a fraction of Kentucky’s 250 dishes were characteristically Kentuckian. Just two hint at African American tradition – macaroni croquettes and okra salad (unless you count fried chicken, but I have covered that in earlier posts).

The Library of Congress says the registered author of the Kentucky Cook Bookwas Mrs. Emma (Allen) Hayes, not the Mrs. W.T. Hayes identified in the Introduction. A search of the Kentucky Death Index turned up five women named Emma Hayes, and one man, a W.T. Hayes. Of the women who were the appropriate age, one Emma was married to W.T. Hayes. W.T. must have been a nickname for Allen, I thought; mystery solved. Well, that is until further investigation revealed that this Mr. And Mrs. Hayes were not colored. They were white.

And I’m not sure it matters. Here’s why.

In a class of American cooks struggling for identity, Emma Hayes laid a foundation for future black cookbook authors, proving that great cooks can and did have vast repertoires that included but were not limited to foods from the fifth quarter. And, even if she was the white mistress who simply helped bring a black woman’s talent to the page, she joins the tiny band of supporters who boldly fought against the plantation cook stereotype by recording recipes and giving them credit for their mastery.

Together these women crossed a dangerous social bridge when they rescued African American cooks from prejudiced interpretations of their character. And that truth leads to an appreciation for the rich culinary legacy created when – not one, but two – cultures came together over bubbling kettles of greens and skillets of pone to evolve an historically important and still beloved cuisine.

Salut!

*

Here is a recipe from the Kentucky Cook Book that hints at the tripe and egg nestled in a satiny tomato sauce we enjoyed today on wine tour. I wonder what wine Mrs. Hayes would recommend?

STEWED KIDNEY WITH TOMATO

After soaking a beef kidney in salt water over night, stew until tender and until little water is left in the kettle. Cut the kidney into small pieces and thicken with flour the water in which it was cooked. Add a tablespoon of butter and the kidney. Serve with boiled tomato and mushroom sauce on toast.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 31, 2010 | Community Cooks

I returned home from Austin’s newest farmer’s market on Saturday feeling a lot like my ancestors in slavery, but without the mad kitchen skills. The day began as a predictable, seasonal treasure hunt for fresh and local produce, cage-free eggs, maybe some grass-fed lamb, and a bar of my favorite lavender-scented handmade soap. The trip quickly turned into a lesson in industriousness and creativity when I encountered the folks selling domesticated Texas Yak.

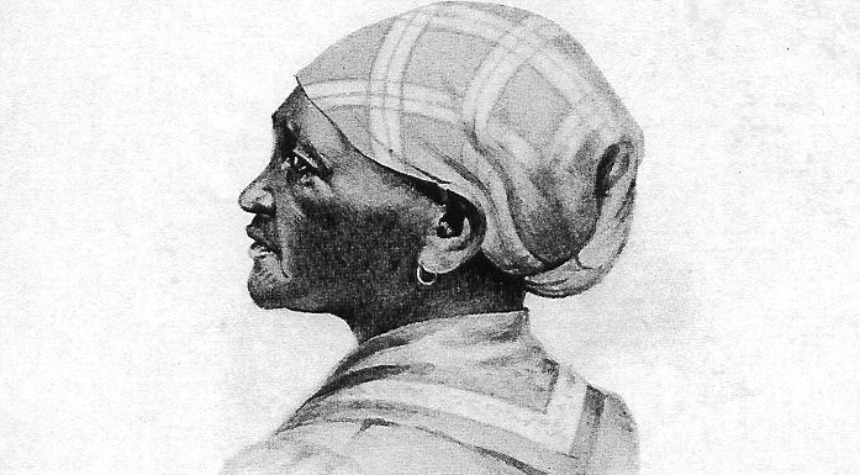

I immediately started channeling my great, great, great grandmother and women like Mary, whose images graced the covers of recipe pamphlets and brochures at the turn of the twentieth century. While domestic scientists in the north, and plantation mistresses in the south were publishing cooking textbooks, like Mrs. Parloa’s New Cook Book, and “entirely original” journals, such as The Virginia Housewife, food manufacturers were printing recipe booklets to teach young cooks how to prepare their latest food inventions. Black cooks were right there in the mix, their images plastered on cookbooks and product labels as statements of culinary authenticity and authority.

The Farmer Jones Cook Book, printed in 1913, clearly reflected this. The collection included recipes for using sorghum syrup in bakery goodies, candies, ice creams, a few meats and vegetables, and a household remedy or two, to “reduce the high cost of living.” Sorghum molasses or syrup is a postassium-rich sweetener produced when sorghum cane is crushed and its juice is cooked down into a thick, dark syrup.

A statement inside the 26-page collection tells us the only thing we know about the cook selected by Farmer Jones to endorse the company’s brand of kitchen wisdom:

“The picture on the front cover is reproduced from life. ‘Mary’ is employed in the family of the Manager of the Fort Scott Sorghum Syrup Co., at Fort Scott, Kansas.”

I wondered what on earth women like Mary thought when they were told to cook unfamiliar foods and the stuff master didn’t want. (Not that the grass-fed, free-range Texas Yak I purchased was cheap like chittlin’s or something fisherman threw away, like catfish. It’s just that consuming Yak meat outside of Tibet is, well, rare; like eating camel.)

After a few rounds of inquiries on Facebook (thanks Leni) and a careful review of game cookery from some early American cookbooks, I did what I figured my ancestors would. I opted for a familiar treatment with trusted results: chicken-fried yak.

I know what you’re thinking. This approach seemed counter-intuitive to me, too. At first.

Yak is after all being promoted as a lean, sweet, delicately-flavored meat that is lower in fat, cholesterol and calories than beef, bison, elk, or even skinless chicken breast. It is so lean, it must be cooked at low temperature, according to Alicia Landin of Texas Yaks.

But I came home with cutlets (think: cube steaks), not filet. This is where industrious creativity kicked in. My family takes most of its meat off the grill. Roasting or pan-frying meats then smothering in a creamy gravy or serving fricassee might have been classic during Mary’s time, but the style is not so familiar in my household.

Surprisingly, the dish turned out to be a perfect choice for an old-fashioned Sunday supper. It came together quickly and easily, and only needed brown rice and a cool crisp salad to be complete. Preparation was quick — just 30 minutes from start to finish. That left enough time for me to whip up Mary’s gingerbread for dessert, accented with sorghum from the Texas Hill Country.

My original locavore ambition was accomplished. Maybe I have some skills after all.

In Her Kitchen

Mary’s Sorghum Gingerbread

Ingredients

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1 1/2 teaspoons ground ginger

- 1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

- 1/2 cup butter, softened

- 1/4 cup brown sugar, packed

- 1 egg

- 1 cup sorghum syrup

- 1 cup lowfat buttermilk

Instructions

- In a bowl, combine flour, baking powder, soda, salt, ginger, and cinnamon. Set aside. Cream together butter and sugar in the bowl of an electric mixer on medium speed, beating until light and fluffy. Add the egg and beat until thoroughly mixed. With mixer running, pour in the sorghum and mix well, scraping down the sides of the bowl occasionally. Add the dry ingredients, alternating with the buttermilk, beginning and ending with the flour mixture. Do not overmix. Pour into a nonstick 8×5-inch loaf pan, sprayed with nonstick vegetable spray. Bake in a preheated 350 degree oven 45 to 50 minutes, or until a wood pick inserted in the center comes out clean. Let rest in pan 10 minutes. Invert onto a wire rack to cool completely before slicing. Serve with sweetened whipped cream.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 24, 2010 | Community Cooks

I was admiring the passionate portraits and poetry of Howard Weeden when the James Beard Foundation announced that two icons of African American culinary arts and foodways studies would be saluted at the Foundation’s prestigious annual Foundation Awards ceremony in May.

The James Beard Foundation Awards were established in 1990 to recognize culinary professionals for excellence and achievement in their fields, and for continued emphasis on the Foundation’s mission: to celebrate, preserve, and nurture this country’s culinary heritage and diversity. This year, Leah Chase, chef/owner of Dooky Chase Restaurant in New Orleans, and Jessica B. Harris, author and historian are among the 2010 Who’s Who of Food & Beverage in America inductees.

What a delicious coincidence.

Both women have worked tirelessly and unapologetically to ensure that African American culinary traditions are kept alive, through published recipes, art and lore even when it was against the industry tide for them to do so, and both inspired my journey to break the Jemima code.

I can remember the delight of my first encounter with Mrs. Chase’s confident culinary wisdom like it was just yesterday. It was during a food and nutrition conference in New Orleans, and a naive journalist marched proudly to the microphone to ask her to explain the difference between “soul” and “southern” food. Mrs. Chase gave an answer that was short and not-too-sweet: “Ours just tastes better.” I smiled a wry smile and never forgot her strong sense of cultural culinary identity.

That brand of assurance seems to have informed Weeden’s work, as well.

Though Weeden was not African American, she captured the art and skill of African American women in the kitchen in a 1898 book of portraits featuring her neighbors’ servants, entitled, Shadows on the Wall. The collection became famous for its passionate portrayals even though it contained the degrading Negro dialect popular at the time.

Aunt Frances, is the subject of one of Weeden’s most recognized poems, Beaten Biscuit. Weeden said that she developed her likeness by “peering at her through the fence,” while the words Weeden wrote about her were by-products of the activities of the domestic science movement.

At that time, domestic duties were moving away from the dark, dim realm of arduous – and frequently demeaning – household chores into the light of art. Ambitious teachers, cooks, writers, and housekeepers excited by the growing link between science and housework were more or less obsessed with transforming American households to make them look as if they were running by themselves.

Domestic scientists established cooking schools, kitchen laboratories, magazines, organizations, and clubs based on the new idea promoted by their leaders, to “develop respect for the kitchen and bring haphazard cooking methods in line with the operations of a well-regulated office or factory,” and to give housewives a new mantle of dignity.

Meanwhile, Howard Weeden was crafting gorgeous alternative images for women cooking amazing food without rules and regulations. Weeden’s artistry speaks unmistakeable truth about the culinary expertise and authority of black cooks, and it is just as compelling as a savory sampling of Creole cuisine at Dooky Chase or an historical anecdote from Jessica’s culinary anthropology.

See for yourself.

BEATEN BISCUIT

by Howard Weeden

Of course I’ll gladly give de rule

I meks beat-discuit by,

Dough I ain’t sure dat you will mek

Dat bread de same as I.

‘Case cooking’s like religion is —

Some’s ‘lected, an’ some ain’t,

An’ rules don’t no more mek a cook,

Den sermons mek a Saint.

Well, ‘bout de ‘grediances required,

I needn’t mention dem,

Of course you knows of flour an’ things,

How much to put, an’ when’

But soon as you is got dat dough

Mixed up all smoove an’ neat,

Den’s when your genius gwine to show,

To get them biscuit beat!

Two hundred licks is what I gives

For home-folks, never fewer,

An’ if I’m spectin’ company in,

I gives five hundred sure!

Author’s Note: The image of Aunt Frances is reprinted from Weeden collection of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

Comments