I was admiring the passionate portraits and poetry of Howard Weeden when the James Beard Foundation announced that two icons of African American culinary arts and foodways studies would be saluted at the Foundation’s prestigious annual Foundation Awards ceremony in May.

The James Beard Foundation Awards were established in 1990 to recognize culinary professionals for excellence and achievement in their fields, and for continued emphasis on the Foundation’s mission: to celebrate, preserve, and nurture this country’s culinary heritage and diversity. This year, Leah Chase, chef/owner of Dooky Chase Restaurant in New Orleans, and Jessica B. Harris, author and historian are among the 2010 Who’s Who of Food & Beverage in America inductees.

What a delicious coincidence.

Both women have worked tirelessly and unapologetically to ensure that African American culinary traditions are kept alive, through published recipes, art and lore even when it was against the industry tide for them to do so, and both inspired my journey to break the Jemima code.

I can remember the delight of my first encounter with Mrs. Chase’s confident culinary wisdom like it was just yesterday. It was during a food and nutrition conference in New Orleans, and a naive journalist marched proudly to the microphone to ask her to explain the difference between “soul” and “southern” food. Mrs. Chase gave an answer that was short and not-too-sweet: “Ours just tastes better.” I smiled a wry smile and never forgot her strong sense of cultural culinary identity.

That brand of assurance seems to have informed Weeden’s work, as well.

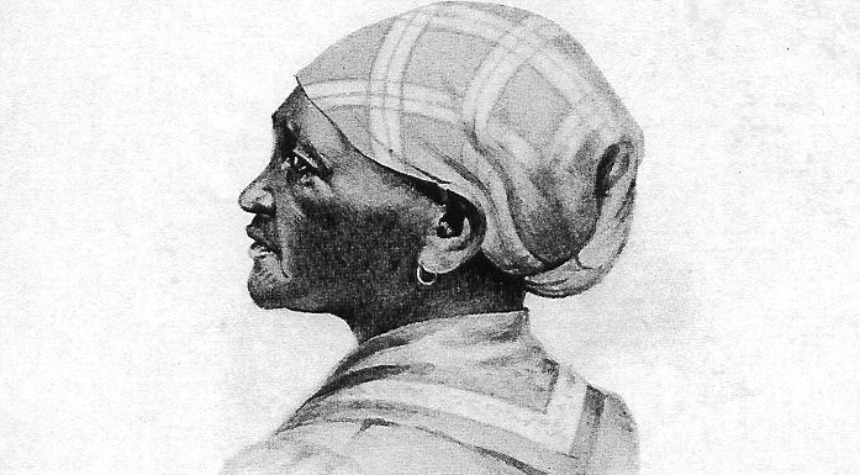

Though Weeden was not African American, she captured the art and skill of African American women in the kitchen in a 1898 book of portraits featuring her neighbors’ servants, entitled, Shadows on the Wall. The collection became famous for its passionate portrayals even though it contained the degrading Negro dialect popular at the time.

Aunt Frances, is the subject of one of Weeden’s most recognized poems, Beaten Biscuit. Weeden said that she developed her likeness by “peering at her through the fence,” while the words Weeden wrote about her were by-products of the activities of the domestic science movement.

At that time, domestic duties were moving away from the dark, dim realm of arduous – and frequently demeaning – household chores into the light of art. Ambitious teachers, cooks, writers, and housekeepers excited by the growing link between science and housework were more or less obsessed with transforming American households to make them look as if they were running by themselves.

Domestic scientists established cooking schools, kitchen laboratories, magazines, organizations, and clubs based on the new idea promoted by their leaders, to “develop respect for the kitchen and bring haphazard cooking methods in line with the operations of a well-regulated office or factory,” and to give housewives a new mantle of dignity.

Meanwhile, Howard Weeden was crafting gorgeous alternative images for women cooking amazing food without rules and regulations. Weeden’s artistry speaks unmistakeable truth about the culinary expertise and authority of black cooks, and it is just as compelling as a savory sampling of Creole cuisine at Dooky Chase or an historical anecdote from Jessica’s culinary anthropology.

See for yourself.

BEATEN BISCUIT

by Howard Weeden

Of course I’ll gladly give de rule

I meks beat-discuit by,

Dough I ain’t sure dat you will mek

Dat bread de same as I.

‘Case cooking’s like religion is —

Some’s ‘lected, an’ some ain’t,

An’ rules don’t no more mek a cook,

Den sermons mek a Saint.

Well, ‘bout de ‘grediances required,

I needn’t mention dem,

Of course you knows of flour an’ things,

How much to put, an’ when’

But soon as you is got dat dough

Mixed up all smoove an’ neat,

Den’s when your genius gwine to show,

To get them biscuit beat!

Two hundred licks is what I gives

For home-folks, never fewer,

An’ if I’m spectin’ company in,

I gives five hundred sure!

Author’s Note: The image of Aunt Frances is reprinted from Weeden collection of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

wow. and not a moment too soon. or as they sa in my native country: better late than never!

Maybe you’ll be next!

Thanks to our Facebook fans we have this lovely interview with Ms. Chase. Enjoy! http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OpESAMEP7rk

A vacuum is the top of cleansing tools; it can be the more costly.

You can find several different sorts of vacuum with various attributes.

So before purchasing a premier hoover make sure you know which kind of vacuum cleaner is most appropriate for

your demands.

Choosing the best hoover can be vexing. To simply help make points

better you should know what the different types of hoover are, what the principal qualities it’s possible

to find on a vacuum cleaner, and need you variety of flooring you will be

employing a hoover on.