by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 13, 2010 | Kitchen Tales

Pauline Brown wasn’t the kind of woman to let segregation bring her down. “I have my share of memories, some of them exciting, some of them scary, but I still love every moment and I will fight for Clarksville until the day I die. This is my area; our home.”

In a somber voice that mobilizes with gripping tales of growing up black in a segregated quarter of Austin, without street lights or indoor plumbing, she reflects on the importance of preserving community. In another interview, the topic turns light-hearted. “I made the richest lemon pie in Clarksville or anyplace else.” Virtually every story she told bewitched with a spirit of unity, and the hope for a brighter future.

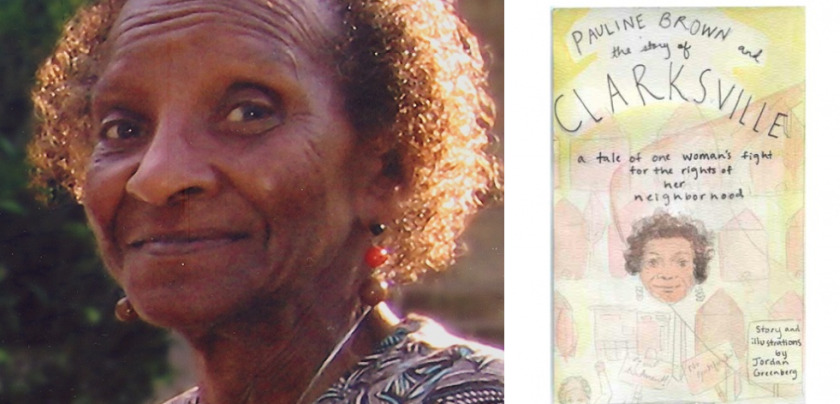

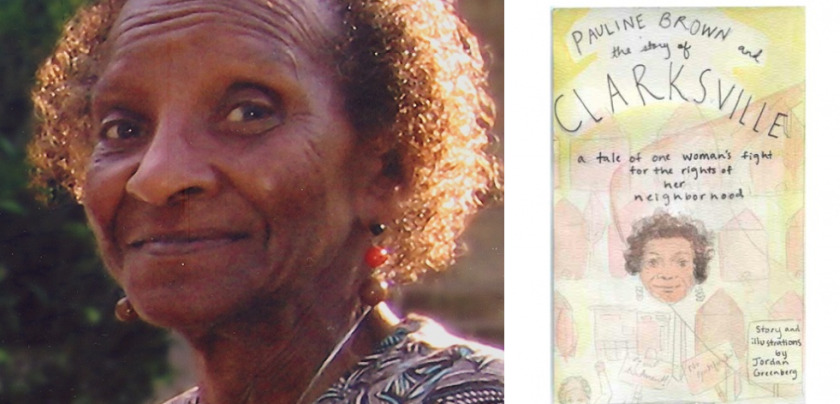

I never met Pauline Brown; I got to know her because of the impression she left on a young high school student named Jordan Greenberg, and on the entire neighborhood of Clarksville, a town founded by the former slaves of Texas Govenor Elisha M. Pease.

Pauline Brown’s story-telling at the Austin Batcave, a nonprofit writing center for kids, captivated Jordan. “I was really struck by her words and felt that the stories and memories she told were beautiful. I thought a lot about her and what she said long after the interview was over, and even more so after I read about her passing (away) just a few weeks later.”

Jordan was so certain that Pauline’s “amazing accomplishments” would connect with children, that she decided to write and illustrate a scholarship-winning book about Pauline’s efforts to save historic Clarksville from urban sprawl. The little book is a tender-hearted reflection on the lives former slaves scraped together. It is also an ode to the wisdom that kept bitterness at bay.

The “ville” of Pauline’s youth is gone. Precious few of its tin-roofed, shot-gun styled homes still dot the wooded and hilly landscape. They have been replaced by a global village and modern, suburban architecture. But, her insights and ambitions linger like the sweet aroma of fresh-baked pie:

“Never forget where you come from.”

“These are great times, please use [them] wisely.”

“Love yourselves.”

“Thank your mother and father, or whoever is taking care of you.”

“Do your part; help wherever you can.”

“Please stay in school.”

“And, remember: this is Clarksville the first freedom town west of the Mississippi, founded in 1871.”

*

Pauline Brown’s memory will be honored this weekend in Austin at the Second Annual Dream Pie Social at Sweet Home Missionary Baptist Church in Clarksville, one of four old-fashioned community gatherings planned to uplift the community in celebration of the Martin Luther King Jr., Holiday. I joined the ServeaDream Organizing Committee, because a pie social encourages citizens of every stripe to come together, and savor food and memories while raising money to preserve the community — even though I admit that being so close to the disregarded family homes and accomplishments has made me a little weary.

Thank goodness for new friends and the precious lore of strong, affirming women like Pauline Brown.

Jordan sums it this way:

“Pauline’s story is proof of the adage that ‘one person can make a difference.’ She was a leader in her community who was truly effective and was also a warm and loving person. Pauline is everything a person can hope for in a role model or heroine; she was brave and determined and also compassionate and kind. She was a strong leader in the community but also a gentle and loving participant… I am very grateful that I have been able to directly give back to the community I was so inspired by.”

Who inspires you?

If you would like to know more about Austin’s Dream Pie Socials, please visit: www.serveadream.org

In Her Kitchen

Lemon Meringue Pie

Ingredients

- 1 1/2 cups water

- 1/3 cup cornstarch

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 cup cold water

- 1 3/4 cups granulated sugar

- 3 eggs, separated

- 2 tablespoons butter

- 1 tablespoon grated lemon zest

- 1/2 cup freshly-squeezed lemon juice

- 1 baked (9-inch) pie shell

- 1/4 teaspoon cream of tartar

- 1/4 teaspoon lemon extract

Instructions

- Bring 1 1/2 cups water to a boil. Dissolve the cornstarch and salt in the cold water. Add to the boiling water, stirring with a wire whisk. Allow to cook until thickened, about 5 minutes. Add 1 1/4 cups of granulated sugar and bring to a boil, then remove from the heat. In a small bowl, beat the egg yolks. Beat a little of the hot liquid into the yolks, then add the yolk mixture to the hot mixture. Stir in the butter. Return to th heat and cook over low heat, stirring constantly, until the filliing boils. Cook 1 to 2 minutes, then remove from the heat. Add the lemon zest and juice and beat with a wire whisk to cool slightly. Set aside 30 minutes. Pour into the pie shell and let cool. Preheat the oven to 400 degrees. Beat the cream of tartar with the egg whites until frothy, then beat until soft peaks form. Gradually beat in the remaining 1/2 cup sugar and the lemon extract, and continue to beat until stiff peaks form, about 2 minutes. Spread the meringue onto the cooled lemon filling, spreading to the edge of the crust to seal. Bake until firm and golden, about 6 to 8 minutes. Allow to cool on a rack to room temperature, then refrigerate at least 3 to 4 hours before serving.

Note: Topping the cooled filling with the meringue will prevent weeping.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 6, 2010 | Plantation Cooks

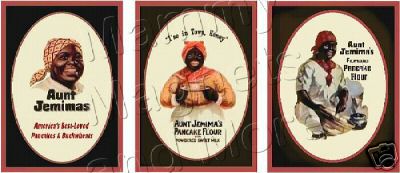

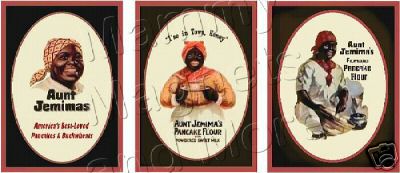

Scholars tell us that Aunt Jemima was the professional persona for household slave women generically identified in literature and history as the plantation Mammy. They say that this obsession with mythical mammies obscured the work of real southern domestic servants, making them little more than a figment of the romantic imaginations of southerners, concocted from a recipe based on “not one truth but a variety of truths and lies told by different people in different circumstances at different times for different reasons.”

In order to break the Jemima Code and find a place for African American women at the long table of American culinary history, I had to forget this kind of academic wrangling about whether mammy ever existed, and instead fill in the mammy outline with clues from multiple sources, including the writings of slaveholding families, because they are the ones who left written documentation of food experiences and practices — even though slaveholding families did not make up the majority in early America.

Interestingly, when these women registered their thoughts, emotions and opinions in their diaries, household journals and letters to family and friends the writings contained few references to meal preparation except as part of the daily routine of plantation living. They state that household slaves were assigned various domestic duties as cooks, laundresses, seamstresses, nurses, and housekeepers. They dressed in the clothes of the family. Ate better food than field slaves. Received medical treatment, and some learned to read and write, despite prohibitive slave codes that prohibited educating them.

When the mistress said, “I planted 60 acres of oats today,” she usually meant she supervised the day’s agricultural chores, not that she actually did the work herself. And, according to her texts, “Chloe,” “Aunt Rachel,” and “Mammy” all cooked. By the time the mistress’s ruminations appeared on the pages of southern ladies literature, Chloe and Rachel’s contributions, their character traits, and identity fuse into one larger-than-life, simplified woman named Mammy. And, in fiction, Mammy did everything.

Mammy affirmed the abolitionists’ stance that slavery was bad while she maintained the segregationists’ view of social hierarchy. Post-Reconstruction Mammy, reflected the new social order, too. She consoled desperate housewives, assured neophyte cooks with creative ingenuity, and at the same time was the source of America’s increasing servant problem. Mammy defended the homestead. Mammy saved the baby. Mammy trained the children, and on occasion, the Misses. Mammy cooked from memory. Mammy made the best pancakes. And, Mammy set a table that invited everyone to come.

She inspired a “Mammy craze,” which swept the nation, between the 1890s and the 1920s, says Cheryl Thurber. In 1923, the United Daughters of the Confederacy demanded that a monument to Mammy be erected in her memory at he nation’s capital. And, in 1924, a New York shop window advertised a fascinating new style for women: an audaciously colored scarf, ‘the Paris version of mammy’s old Southern bandana.”

If we only think about an African American cook’s lowly station of life, the minimal culinary contributions credited to her by historians and cookbook writers, and the exaggerated and distorted pictures used to misrepresent her intelligence, then it is, of course, impossible to believe that she could have been anything more than a simple laborer.

Fortunately, there is an alternative view.

In 1938, Eleanor Ott published a fanciful collection of New Orleans-styled recipes, entitled Plantation Cookery of Old Louisiana, which illustrates the degree of specialization and expertise known among black cooks. In it, Ott details her grandmother’s vast “culinary plant” with its numerous adjunct buildings and “mammies” assigned to each house. At Fair Oaks Plantation, Kitty Mammy managed the vegetables and herb garden and Becky Mammy was the “high priestess of the milk-house,” while “some colored sub-cook was only too pleased to sit for eight hours…to keep an eye on a kettle of simmering pot-au-feu.”

The Culinary Institute of America’s programs catalog might define these “Mammy” tasks in a more professional way, with Kitty, Becky, and the no-named Mammy each as technicians of Vegetarian Cooking: Strategies for Building Flavor; Baking and Pastry; and Soups, Stocks and Sauces.

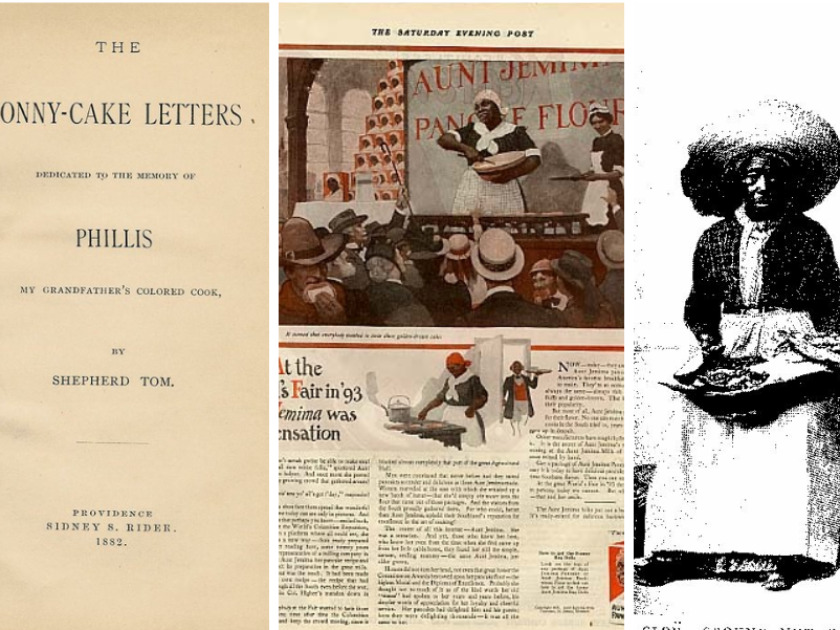

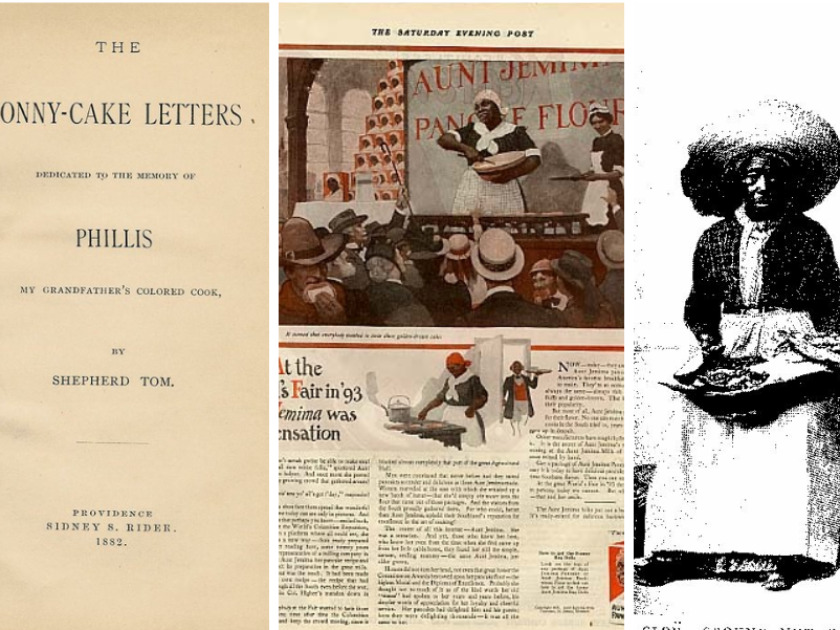

And, then there is, The Jonny-Cake Letters, Dedicated to the Memory of Phillis My Grandfather’s Colored Cook, a journal written in 1882 by Thomas R. Hazard of Rhode Island. Phillis is Hazard’s muse. She is “universally admired.” Is the “remote cause of the French Revolution and the death of Louis 16th and Marie Antoinette.” And, she reportedly bakes the most seductive jonny cake Hazard has ever tasted. Within Hazard’s exaggerated family tales are more than a few observations of Phillis’ culinary proficiency, which are so deeply enmeshed with his food recollections it is difficult to tell which comes first: his love of food or his passion for the skill of Phillis.

And, it really does not matter.

Phillis’ jonny cake “made one’s mouth water to look at it,” her assorted rye breads were “prized above rubies,” and this woman known only as his grandfather’s old kitchen cook from Senegambia or Guinea, was as an “artist” capable of inspiring others while tending the pot.

Like the assorted mammies of Fair Oaks plantation, Phillis’ culinary talents give the black cook’s shadows some substance, and there is evidence associating Mammy characteristics with real black cooks found in black sources, as well.

In slave culture, Mammy was a common name for mothers, and elders were addressed as “Aunty,” “Mauma and “Maum,” or “Mammy” as a mark of respect, not kinship. In the 1880 census the mythical Aunt Jemima is linked to at least one real, living African American woman, a black female servant who lists “cook” as her occupation and Mother Jemima as her name. The name Jemimah implied blessings and a message of hope, not subservience, according to Old Testament Scripture found in Job 42:12-14, and slaves, evidently knew it.

So, I am not at all surprised that legendary cooks and ex-slaves with a worthy name were brought to life in a marketing campaign created by a couple of guys trying to sell more pancake flour.

Are you?

In Her Kitchen

Whole Wheat Pancakes

Ingredients

- 2 cups whole wheat flour

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- 2 eggs

- 2 cups buttermilk

- 6 tablespoons unsalted butter

Instructions

- Whisk together the flour, baking powder, soda, salt and sugar. In a separate bowl, combine the eggs, buttermilk and 4 tablespoons butter. Make a well in the center of the dry ingredients and pour in the liquid ingredients. Stir together until just mixed. Batter will be lumpy. Heat a nonstick griddle over medium-high heat. Brush lightly with remaining 2 tablespoons butter, and using a 1/4 cup measure, ladle batter onto griddle for each pancake. Reduce heat to medium and bake pancakes until the top is bubbly and the edges begin to crisp, about 2 minutes. Using a wide spatula, turn pancakes over and cook on other side 1 minute longer. Do not flatten pancakes. Remove to serving platter and keep warm. Wipe griddle with paper towels, then repeat process with remaining butter and batter.

Number of servings: 4

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Dec 30, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

So we went to a cocktail party last night to celebrate the coming of the New Year and the inevitable question came up.

“What do you do?”

I explain that I have just started blogging about the history of African American cooks, and before I can finish my sentence, a woman who looked like she would know better, glared over her glass of Tempranillo and asked, “Why are you still worrying about what happened 200 years ago? It’s in the past; get over it.”

“Well, I can’t get over it,” I scold her. “Neither should you.”

Here’s why:

In 2002, Texas A&M University’s student newspaper, The Battalion, published a political cartoon, which resembled the kind of degrading Jim Crow-era imagery that appeared routinely on manufacturer’s labels, in advertising, magazines, and Southern daily newspapers. Only worse.

The illustration depicted a large black woman wearing an apron, holding a spatula, and chastising her son at TAKS Test time. The Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills exams (TAKS) are serious business for politicians, school districts, and parents in the Lone Star State, and evidently black boys performed pretty poorly that year. Neither the student, nor his or her editor, nor the journalism advisor questioned the suitability of using a bigoted turn-of-the-century image to portray a modern-day mother’s concern for her son’s poor academic performance. I did.

I’d like to agree with the faculty who defended the student’s actions as “an unfortunate mistake” and the woman at the party, who believe that in these “post-racial times” our society does value diversity, abhors “pulling the race card,” and promotes “no color-line” policies, but how can I? The A&M cartoon says that even with re-doubled efforts, our high-technology children cannot see beyond the narrow Aunt Jemima cliché. How can they?

Everywhere you look, the image of African American mothers is stuck in 1900.

Media credentials legitimize journalistic lapses, such as this. Radio disc jockeys like John “Sly” Sylvester” and Don Imus get a pass. Black men in rank drag acts, including Eddie Murphy as Norbit and Tyler Perry as Madea are modern-day re-creations of bigoted minstrelsy and Negro impersonation. And don’t even get me started about the Pine Sol Lady and Lisa from the “Get Mommed” Kleenex ad. It’s as if there was a sign on the casting call door that reads: “Only big girls need apply.”

Please don’t get it twisted; this is not a slam against plus-sized women. What I’m saying is that in the absence of a written history to defy – or at least counter-balance the stereotype – the picture of every African American woman in our national minds’ eye resembles a rude trademark. That shallow image ignored the powerful love language of mother’s kitchen, and even worse, cataloged her skill and virtues as anything but extraordinary in a file marked “idiot savant.”

To be a patient and loving wife and mother; to be smart, talented, hard-working, physically and emotionally strong, yet compassionate; to multi-task: these are the characteristics that intersect in the black women who fed this nation, but they are lost in lampoon.

Which makes two things clear to me: In the year 2010, we need a new picture to replace the Aunt Jemima asymmetry. And, adults like those at A&M who still think that it is appropriate to classify stereotyped imagery as satire should not be teaching anybody. At all.

In order to wrap up this heated conversation with my dinner companion, we take one more trip to the Internet. I tell her about a recent Google search of the culinary cliche “slaving in the kitchen.” I name some of the assorted modern convenience foods, gadgets, and equipment that popped up — all designed to save time and effort in the kitchen — including a Japanese knife called the “kitchen slave,” which offers “simplicity, utilitarian attitude, and beautiful elegance.” Then I contend that the Jemima Code is a uselful, new tool with a similar twist on the theme.

I say that as we enter the season of new priorities and make resolutions to begin this or quit that, we should use this journal to cut through historical rhetoric and expose the wisdom and of poetry of African American culinary artists, to bring their skill and professional excellence into the light.

At last, she relents; the conversation moves on.

So why did I call it the Jemima Code?

Merriam-Webster defines a code as “a body of laws systematically arranged for easy reference; especially one given statutory force; a system of principles or rules (as in moral code); a system of signals or symbols for communication used to represent assigned and often secret meanings.”

To decode, the dictionary goes on to say, is “to convert a coded message into intelligible form; to recognize and interpret a signal; or to discover the underlying meaning of.”

As Americans, we live with all sorts of standardizing codes – dress codes, moral codes, codes of conduct, codes of law, bar codes. Recipes are codes. So are prescriptions. But when we talk about a “Jemima Code,” we see how arrangement of words and images synchronized to classify the character and life’s work of our nation’s black cooks into an insignificant symbol contrived to communicate a powerful double message, based upon exaggerated principles and secret meaning.

Like most codes, the Jemima Code is a 200-year-old system of prejudices and double standards that originated in the hand-written journals and ledgers of slaveholding women and their letters to family and friends. Their inconsistent, emotional observations bloated the image of female house servants. Opinions about those unrealistic behaviors established character types, and those stereotypes transmitted unwritten messages about black cooks that were open to interpretation.

The result was an image America used as powerful shorthand. Aunt Jemima became the embodiment of our deepest antipathy for and obsession with the women who fed us with grace and skill. In short, a sham.

Ironically, the same observations that created this code can break it; the difference is interpretation.

I don’t believe that gratitude for years of servitude, claiming an absolute, single historical truth about black cooks, or redefining culinary processes with black sensibilities will instantaneously remove the haze of hard labor that obscures the real wisdom of their work — a haze that still lingers over modern kitchens. Truth will.

Historian and scholar Sidney Mintz, speaking several years ago at a dinner in Washington, D.C., impelled the idea for this work when he encouraged the audience to find new ways to exalt America’s unsung heroes of the kitchen – the African American cooks.

He said: “We need to honor those women, not only for their achievements as cooks, but also for the terrible burden they bore, standing as they did at the very crossroads where the idle free and the oppressed unfree were joined – in the kitchen. As we do them honor, we have to imagine the restraint, patience, and intelligence they themselves had to possess in order to go home each night to their own families, their men and their children, having lived through another day in the skilled but un-rewarded service of others in whose power they were.”

To ignore these virtues is like eating fried chicken without the skin: You just know something is missing.

Have some…

In Her Kitchen

Pan-Fried Chicken

Ingredients

- 1 (4-pound) frying chicken, cut up

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- 3/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 teaspoon black pepper

- 1/4 teaspoon garlic powder

- 1/4 teaspoon paprika

- Oil

Instructions

Rinse chicken pieces and pat dry. Place flour, salt, pepper and garlic powder in a small paper bag. Add chicken pieces and shake to coat evenly. Let stand 10 minutes. Heat 3/4- to 1-inch oil in a 9 or 10-inch cast iron skillet to about 375 degrees. Add chicken in batches and cook until chicken is crisp and golden brown, about 10 minutes per side. Do not crowd pan. Drain chicken on paper towels. Serve warm.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Dec 23, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

This was supposed to be the blog that explained the origins of The Jemima Code, but when my 17-year-old son Christian asks you to do something, it’s kind of hard not to agree.

Last night, he and five of his friends took possesion of my kitchen, and prepared a seven-course holiday dinner party straight off the pages of Food and Wine. By the time the evening was over, I had learned a lesson about the spirit of giving and about myself. I had to write about it.

Not because I was at all surprised that Christian’s all-male team of non-cooks was planning to prep and serve a holiday feast to strut for the female half of their little group, or even that he composed a classical menu for the occasion. These kids have spent a long fall semester preparing for graduation — writing essays, applying for college, and maintaining outstanding GPAs. They needed to celebrate.

What took my breath away was that he scheduled the party on a day when I would not be home to help. I teach cooking and have a well-stocked kitchen pantry and cookbook library, and my son figured the gig would be easy and sure to impress whether I supervised or not. But these were high school seniors who’ve been cooped up for months with their heads buried in World Geography textbooks. My thoughts didn’t immediately reflect on all of the lovely culinary experiences Chris and I had shared over the years. Instead, I secretly, okay, vocally, pondered whether I needed to distribute parental liability release forms for kids slicing potatoes and fingers on the mandoline, and envisioned Mushroom Veloute splattered everywhere.

Christian offered some sage advice: “Shhhh. Calm down. There are worse things that could happen three days before Christmas — like the tree catches fire or a burglar steals all the gifts.” He said something wonderful, too.

Christian grew up listening to stories about the unsung heroes of the kitchen who I intend to profile here starting in January, and he congratulated me for becoming one of them. He assured me that the self-confidence and discipline he learned were transferrable skills that he would pass on to the guys as they jabbered about mise en place or the proper technique for folding egg yolks and whites together, just the way I had transmitted them to him all these years.

I knew that Christian always really loved to cook. When he was just 2, he would push a chair up to the sink and demand an assignment.

“Cook, cook,” he cooed.

Later, he began making his own special whole wheat pancakes, which were featured in Edible Austin Magazine’s Summer 2009 issue. Christian has also served as my assistant during summer cooking camps, organizing giddy six-year-olds and regaling 6th graders with his Alton Brown imitation.

With this massive dinner party, he confirmed that the love language of my kitchen had taught him patience and how to follow instructions; he also developed some intangible values, such as discipline and encouragement as we nurtured the most disinterested and intimidated novices into cooking from scratch. My brand of kitchen wisdom, he said, had motivated a bunch of really smart guys to devote an entire afternoon to preparing Kansas City Fritters, Caprese Salad, Herbed Roasted Leg of Lamb, Cheese Souffle, and Tarte Tatin as a gift. I was speechless.

I hope the coming stories of some truly fantastic cooks will inspire you into the kitchen, too. In the meantime, Christian’s Herbed Roasted Leg of Lamb, which he adapted from Food and Wine Magazine, is a delicious place for you to start developing a culinary love language of your own.

In Her Kitchen

Herbed Roasted Leg of Lamb

Ingredients

- One (4.5-pound) trimmed, boneless leg of lamb, butterflied

- Extra-virgin olive oil

- 1/4 cup minced flat leaf parsley, plus 2 sprigs

- 1/8 cup minced fresh rosemary, plus 2 sprigs

- 1/8 cup minced fresh oregano, plus 2 sprigs

- 1 small clove garlic, minced

- Salt, pepper

- 4 small baking potatoes, peeled and quartered

Instructions

Preheat the oven to 375 degrees. Open the leg of lamb on a work surface, fat side down. Drizzle with olive oil and rub in the herbs and garlic. Season with salt and pepper. Roll up the lamb, fat side down, and tie with kitchen twine at 1-inch intervals. Season with salt and pepper. Spray a small roasting pan with nonstick vegetable spray. Place herb sprigs in the bottom of the pan. Top with potatoes. Place roast on top and roast for about 1 hour, or until a thermometer inserted into the meat registers 125 degrees for medium-rare. Transfer to a carving board, tent with foil and let rest for 15 minutes. Strain the juices into a cup and skim off the fat. Discard the strings and thinly slice the roast. Drizzle with the juices and serve with potatoes.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Dec 16, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

I am a Disney girl and everyone knows it. So when the studio announced its intention to release a film with an African American princess, who also happens to be an aspiring chef, I couldn’t have been more excited. I raced to the theater for opening weekend, though I must admit sensing a dark cloud of dread hovering over me as I anticipated the complaints of internet reviewers, and braced for more stereotypes of African American cooks.

After all, this is the same studio that embedded subtle racism in Dumbo and the Jungle Book. And, in the 1950s, Disneyland promoted the Aunt Jemima trademark in its popular restaurant, Aunt Jemima’s Pancake House. Over the years, I was able to overlook those as flaws in a machine that bowed to the social and cultural pressures of its time. But in these “post-racial times, I wondered how they would deal with the New Orleans of 1920 and the limited career options for women of color.

Despite some age-old characterizations about the south and the kitchen in the storyline, critics are gushing, movie-goers pushed the movie to the top of the weekend box-office, and I found the film to be a charming mix of fact and fantasy.

To my surprise, Tiana possesses several of the qualities of the women who will be featured in this journal: she is hard-working with culinary proficiency that is seductive and in high-demand; she has entreprenurial ambitions and skills; she is focused and determined, not waiting around to be rescued by Prince Charming; she is prudent, saving her pennies for a long-term goal (Tiana’s restaurant), she has a very popular cookbook; makes a mean pot of gumbo, and she works selflessly at times to promote the greater good.

Too bad she also is the first Disney princess to spend most of her screen time as an amphibian.

It was also difficult to embrace the image of poverty reflected in Princess Tiana’s Cookbook for children. The book has been sold out for weeks at the Disney store where I live, but her father’s famous recipe for gumbo is posted on Amazon. Unfortunately, the recipe perpetuates the same make-do stereotype of African American cooking that has been promoted for years with its wieners in the mix.

We’ll serve this gumbo over the holidays, instead.

In Her Kitchen

Chicken Gumbo

Ingredients

- 1/2 cup all-purpose flour

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon garlic powder

- 1/4 teaspoon black pepper

- 1/4 teaspoon cayenne red pepper

- 1 (3- to 4-pound) chicken, cut up

- 1 tablespoon each butter and oil

- 1 1/2 cups chopped onions

- 1/4 cup chopped green onions

- 1 cup chopped green bell peppers

- 1 cup chopped celery

- 1 tablespoon minced garlic

- 1 pound smoked sausage, sliced

- 2 quarts chicken broth

- 2 bay leaves

- 2 tablespoons minced fresh parsley

- Hot cooked rice

Instructions

- Place flour in a cast-iron skillet in a 400 degree oven until the flour turns nut-brown, stirring often. Combine seasonings and sprinkle chicken pieces on both sides. Heat butter and oil in a heavy Dutch oven or soup pot. Add a few chicken pieces to the pan cook over medium-high heat until brown. Turn and cook on other side. Do not crowd the pan. Continue cooking and turning chicken until all pieces are done. Remove to a platter and set aside. Add onions, bell peppers, celery and garlic to pan, and cook over medium heat, stirring to loosen browned bits. Add sausage to pan and increase heat to high. Saute 5 minutes longer, until vegetables are slightly browned and carmelized. Meanwhile, place browned flour in a medium-sized bowl. Gradually whisk in 2 cups broth, stirring until flour is completely dissolved and no lumps remain. Add to vegetables along with remaining 6 cups broth and bay leaves. Reduce heat and let gumbo simmer 45 minutes. Do not boil. Use a slotted spoon to remove chicken from pot. Let cool slightly, then remove chicken from the bone and cut into bite-sized chunks. Remove and discard bay leaf. Return chicken to pan, sprinkle with parsely and season to taste with additional salt and pepper. Serve over hot cooked rice.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

Comments