by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 31, 2010 | Community Cooks

I returned home from Austin’s newest farmer’s market on Saturday feeling a lot like my ancestors in slavery, but without the mad kitchen skills. The day began as a predictable, seasonal treasure hunt for fresh and local produce, cage-free eggs, maybe some grass-fed lamb, and a bar of my favorite lavender-scented handmade soap. The trip quickly turned into a lesson in industriousness and creativity when I encountered the folks selling domesticated Texas Yak.

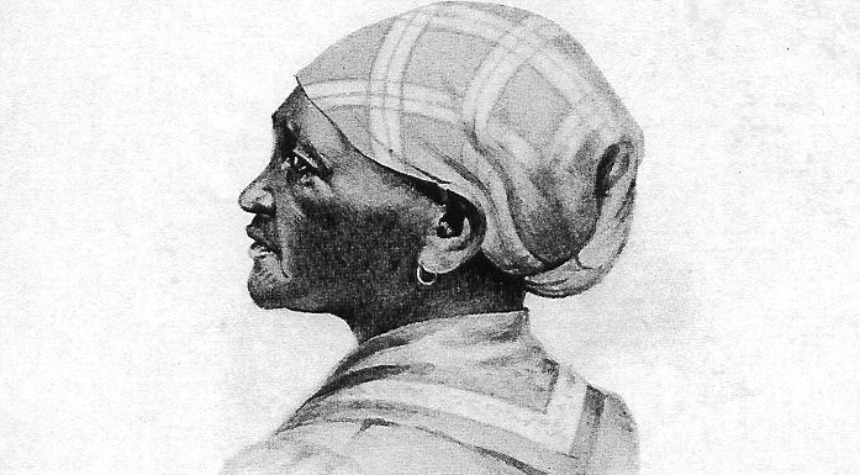

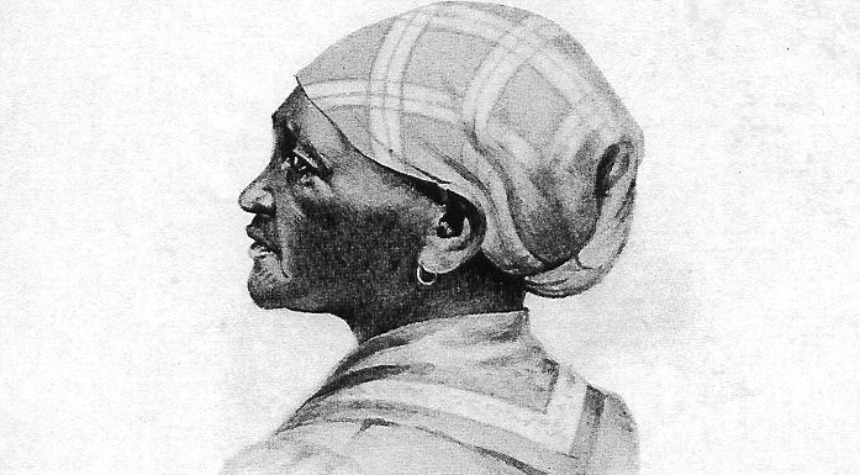

I immediately started channeling my great, great, great grandmother and women like Mary, whose images graced the covers of recipe pamphlets and brochures at the turn of the twentieth century. While domestic scientists in the north, and plantation mistresses in the south were publishing cooking textbooks, like Mrs. Parloa’s New Cook Book, and “entirely original” journals, such as The Virginia Housewife, food manufacturers were printing recipe booklets to teach young cooks how to prepare their latest food inventions. Black cooks were right there in the mix, their images plastered on cookbooks and product labels as statements of culinary authenticity and authority.

The Farmer Jones Cook Book, printed in 1913, clearly reflected this. The collection included recipes for using sorghum syrup in bakery goodies, candies, ice creams, a few meats and vegetables, and a household remedy or two, to “reduce the high cost of living.” Sorghum molasses or syrup is a postassium-rich sweetener produced when sorghum cane is crushed and its juice is cooked down into a thick, dark syrup.

A statement inside the 26-page collection tells us the only thing we know about the cook selected by Farmer Jones to endorse the company’s brand of kitchen wisdom:

“The picture on the front cover is reproduced from life. ‘Mary’ is employed in the family of the Manager of the Fort Scott Sorghum Syrup Co., at Fort Scott, Kansas.”

I wondered what on earth women like Mary thought when they were told to cook unfamiliar foods and the stuff master didn’t want. (Not that the grass-fed, free-range Texas Yak I purchased was cheap like chittlin’s or something fisherman threw away, like catfish. It’s just that consuming Yak meat outside of Tibet is, well, rare; like eating camel.)

After a few rounds of inquiries on Facebook (thanks Leni) and a careful review of game cookery from some early American cookbooks, I did what I figured my ancestors would. I opted for a familiar treatment with trusted results: chicken-fried yak.

I know what you’re thinking. This approach seemed counter-intuitive to me, too. At first.

Yak is after all being promoted as a lean, sweet, delicately-flavored meat that is lower in fat, cholesterol and calories than beef, bison, elk, or even skinless chicken breast. It is so lean, it must be cooked at low temperature, according to Alicia Landin of Texas Yaks.

But I came home with cutlets (think: cube steaks), not filet. This is where industrious creativity kicked in. My family takes most of its meat off the grill. Roasting or pan-frying meats then smothering in a creamy gravy or serving fricassee might have been classic during Mary’s time, but the style is not so familiar in my household.

Surprisingly, the dish turned out to be a perfect choice for an old-fashioned Sunday supper. It came together quickly and easily, and only needed brown rice and a cool crisp salad to be complete. Preparation was quick — just 30 minutes from start to finish. That left enough time for me to whip up Mary’s gingerbread for dessert, accented with sorghum from the Texas Hill Country.

My original locavore ambition was accomplished. Maybe I have some skills after all.

In Her Kitchen

Mary’s Sorghum Gingerbread

Ingredients

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1 1/2 teaspoons ground ginger

- 1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

- 1/2 cup butter, softened

- 1/4 cup brown sugar, packed

- 1 egg

- 1 cup sorghum syrup

- 1 cup lowfat buttermilk

Instructions

- In a bowl, combine flour, baking powder, soda, salt, ginger, and cinnamon. Set aside. Cream together butter and sugar in the bowl of an electric mixer on medium speed, beating until light and fluffy. Add the egg and beat until thoroughly mixed. With mixer running, pour in the sorghum and mix well, scraping down the sides of the bowl occasionally. Add the dry ingredients, alternating with the buttermilk, beginning and ending with the flour mixture. Do not overmix. Pour into a nonstick 8×5-inch loaf pan, sprayed with nonstick vegetable spray. Bake in a preheated 350 degree oven 45 to 50 minutes, or until a wood pick inserted in the center comes out clean. Let rest in pan 10 minutes. Invert onto a wire rack to cool completely before slicing. Serve with sweetened whipped cream.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 24, 2010 | Community Cooks

I was admiring the passionate portraits and poetry of Howard Weeden when the James Beard Foundation announced that two icons of African American culinary arts and foodways studies would be saluted at the Foundation’s prestigious annual Foundation Awards ceremony in May.

The James Beard Foundation Awards were established in 1990 to recognize culinary professionals for excellence and achievement in their fields, and for continued emphasis on the Foundation’s mission: to celebrate, preserve, and nurture this country’s culinary heritage and diversity. This year, Leah Chase, chef/owner of Dooky Chase Restaurant in New Orleans, and Jessica B. Harris, author and historian are among the 2010 Who’s Who of Food & Beverage in America inductees.

What a delicious coincidence.

Both women have worked tirelessly and unapologetically to ensure that African American culinary traditions are kept alive, through published recipes, art and lore even when it was against the industry tide for them to do so, and both inspired my journey to break the Jemima code.

I can remember the delight of my first encounter with Mrs. Chase’s confident culinary wisdom like it was just yesterday. It was during a food and nutrition conference in New Orleans, and a naive journalist marched proudly to the microphone to ask her to explain the difference between “soul” and “southern” food. Mrs. Chase gave an answer that was short and not-too-sweet: “Ours just tastes better.” I smiled a wry smile and never forgot her strong sense of cultural culinary identity.

That brand of assurance seems to have informed Weeden’s work, as well.

Though Weeden was not African American, she captured the art and skill of African American women in the kitchen in a 1898 book of portraits featuring her neighbors’ servants, entitled, Shadows on the Wall. The collection became famous for its passionate portrayals even though it contained the degrading Negro dialect popular at the time.

Aunt Frances, is the subject of one of Weeden’s most recognized poems, Beaten Biscuit. Weeden said that she developed her likeness by “peering at her through the fence,” while the words Weeden wrote about her were by-products of the activities of the domestic science movement.

At that time, domestic duties were moving away from the dark, dim realm of arduous – and frequently demeaning – household chores into the light of art. Ambitious teachers, cooks, writers, and housekeepers excited by the growing link between science and housework were more or less obsessed with transforming American households to make them look as if they were running by themselves.

Domestic scientists established cooking schools, kitchen laboratories, magazines, organizations, and clubs based on the new idea promoted by their leaders, to “develop respect for the kitchen and bring haphazard cooking methods in line with the operations of a well-regulated office or factory,” and to give housewives a new mantle of dignity.

Meanwhile, Howard Weeden was crafting gorgeous alternative images for women cooking amazing food without rules and regulations. Weeden’s artistry speaks unmistakeable truth about the culinary expertise and authority of black cooks, and it is just as compelling as a savory sampling of Creole cuisine at Dooky Chase or an historical anecdote from Jessica’s culinary anthropology.

See for yourself.

BEATEN BISCUIT

by Howard Weeden

Of course I’ll gladly give de rule

I meks beat-discuit by,

Dough I ain’t sure dat you will mek

Dat bread de same as I.

‘Case cooking’s like religion is —

Some’s ‘lected, an’ some ain’t,

An’ rules don’t no more mek a cook,

Den sermons mek a Saint.

Well, ‘bout de ‘grediances required,

I needn’t mention dem,

Of course you knows of flour an’ things,

How much to put, an’ when’

But soon as you is got dat dough

Mixed up all smoove an’ neat,

Den’s when your genius gwine to show,

To get them biscuit beat!

Two hundred licks is what I gives

For home-folks, never fewer,

An’ if I’m spectin’ company in,

I gives five hundred sure!

Author’s Note: The image of Aunt Frances is reprinted from Weeden collection of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 17, 2010 | Entrepreneurs

As a journalist at a bloggers workshop, I was feeling a little bothered while attending South by Southwest Interactive (SXSW) this week, like a wolf in sheep’s clothing, until I realized that the women who inspire me also lived as if there were four of them.

They published cookbooks. Operated retail food businesses. Invented culinary gadgets. Hawked food products. Taught home economics. Catered lavish events. Sometimes, all at once.

As an author, I loved getting to know Abby Fisher and Malinda Russell, and imagining the kind of intelligent and creative recipes that my ancestors might have published if given the opportunity.

This week, I find muse in Kentucky, looking for the perfect mint julep to serve at a catered event next month, where I will be speaking about and teaching southern food traditions, and maybe making a dish or two.

Who me? Multi-task?

The first artifact is The Blue Grass Cook Book, by Minnie C. Fox.

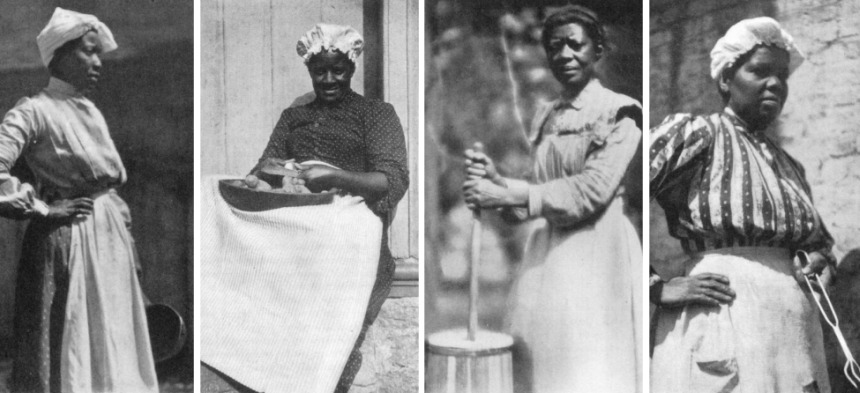

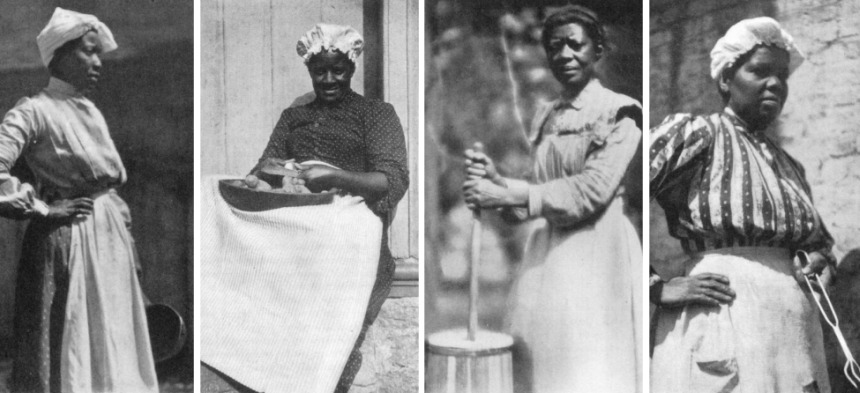

Although it was not written by a black cook, the University Press of Kentucky and I published the historic reprint of Blue Grass in 2005 because it is the first-known cookbook to offer an honest and revealing picture of the state of culinary affairs in the South at the start of the twentieth century. It features more than 300 recipes and a dozen stunning camera portraits – not caricatures – of African American cooks at work. They are pictured above.

More directly than anyone before them – or after, until mid-century – Minnie, and her novelist brother John, publicly acknowledged the black contribution to Southern foodways, Southern culture, and Southern hospitality in 1904. In what amounts to direct and explicit homage, Minnie applauds the “turbaned mistress of the kitchen” for her dignity, wisdom, and talent.

This picture casts a bold shadow of hope and grace on the Aunt Jemima make-believe.

John Fox’s introduction and the photographs of Alvin Langdon Coburn do for these great cooks what historians, cookbook authors, novelists, advertisers, and manufacturers simply did not: They single out for full recognition and credit the black cook as the near-invisible but indispensable figure who made Southern cuisine famous.

Meanwhile, as housewives produced textbooks that emphasized the technical basics of cooking at the turn of the twentieth century, Effie Waller Smith wrote poetry that made powerful statements about the competencies of her African American sisters in the kitchen.

The authority and observations in her collected works, which were discovered and republished by the Schomburg Library in 1991, include interpretation, so I’ve simply included my favorite poem here for you to enjoy, and hopefully to share.

Maybe next time, I’ll attend a meeting of anthropologists.

APPLE SAUCE AND CHICKEN FRIED

By Effie Waller Smith, 1904

You may talk about the knowledge

Which our farmers’ girls have gained

From cooking-schools and cook-books

(where all modern cooks are trained);

But I would rather know just how,

(Though vainly I have tried)

To prepare, as mother used to,

Apple sauce and chicken fried.

Our modern cooks know how to fix

Their dainty dishes rare.

But, friend, just let me tell you what!–

None of them compare

With what my mother used to fix,

And for which I’ve often cried,

When I was but a little tot,–

Apple sauce and chicken fried.

Chicken a la Francaise,

Also fricassee,

Served with some new fangled sauce

Is plenty good for me,

Till I get to thinking of the home

Where I used to ‘bide

And where I used to eat, — um, my!

Apple sauce and chicken fried.

We always had it once a week,

Sometimes we had it twice;

And I have even known the time

When we have had it thrice.

Our good, yet jolly pastor,

During his circuit’s ride

With us once each week gave grateful thanks

For apple sauce and chicken fried.

Why, it seems like I can smell it,

And even taste it, too,

And see it with my natural eyes,

Though of course it can’t be true;

And it seems like I’m a child again,

Standing by mother’s side

Pulling at her dress and asking

For apple sauce and chicken fried.

Author’s Note: Use caution if you purchase The Blue Grass Cook Book from Amazon. Applewood Books is offering a reprinted copy that does not include my historical background on the Fox family. If you would like to purchase an autographed copy of The Blue Grass Cook Book, please email me.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 15, 2010 | Entrepreneurs

Kick me for not straight out calling the women in my last post top chef-styled celebrities, and for not telling you that you can and should own copies of their work — the first black cookbooks published in this country.

It’s just that I lost my webmaster and I was going a little crazy at post time. I don’t make a dime off of sales of these books. I just think they are valuable additions to anyone’s cookbook collection. And, if you aren’t collecting books yet these are a great place to start. Indulge me, as I fuss over them a little while longer.

At the end of the 20th century, cookbooks were called household manuals. They emphasized domestic economy and food science, and included “tested” receipts, the old-school word for recipes.

The most popular texts encouraged young housewives to “get rid of the false sentiment that grades different ranks of work as more or less respectable,” and reminded them that “cooking “possesses the dignity of an art, of science, and of philosophy.”

At the same time, most authors of these books claimed that black cooks were too ignorant to be able to translate the recipes from their heads to the written page. If the cook was credited, her recipe was written in illiterate language meant to demean.

But Malinda Russell and Abby Fisher dispute this image. Their little books reveal cooks who truly understood technique, whether they shared that information with the mistress or not. They might not have understood the hydrogen ION concentration and pH of some common foods, but both women were counted among those sensible and experienced cooks of their communities. Each one shared the love of good food and cooking with friends.

*

The limited-edition facsimile reprint of Malinda Russell’s A Domestic Cook Book: Containing Useful Receipts for the Kitchen, (printed in 1866), is available from the University of Michigan. The booklet was edited by Jan Longone and costs $25.

What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, published in 1881 by Abby Fisher, may be purchased through Amazon.

Malinda Russell’s Elizabeth Lemon Cake is a lovely springtime pound cake, which I make even more special for family and friends by drizzling with a a sweet-tart glaze of Meyer lemon juice and powdered sugar.

In Her Kitchen

Elizabeth’s Lemon Cake

Ingredients

- 1 cup unsalted butter, at room temperature

- 2 1/2 cups granulated sugar

- 5 large eggs

- 1/4 cup grated lemon zest

- 3 cups all-purpose flour

- 1/2 teaspoon baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 cup buttermilk

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- 1/2 cup freshly-squeezed lemon juice

- Tangy Lemon Glaze

Instructions

- Have all ingredients at room temperature. Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Grease and flour a 12-cup fluted tube pan or 2 (8×4-inch) loaf pans. Cream together the butter and 2 cups of the sugar in the bowl of an electric mixer until light and fluffy, about 5-7 minutes. Gradually beat in the eggs, one at a time, beating well after each addition. Beat in the lemon zest. Sift together the flour, baking powder, soda, and salt in a bowl. Combine buttermilk and vanilla. With the mixer on low speed, alternately beat in the dry and liquid ingredients, beginning and ending with the dry ingredients. Pour the batter into the prepared pan and bake for 50-60 minutes or until a wood tester inserted in the center comes out clean. Combine remaining 1/2 cup sugar with lemon juice in a small saucepan and cook over low heat until sugar dissolves. When cake is done, use a skewer to poke holes over the entire top. Carefully spoon the lemon syrup over the cake, allowing syrup to soak in before adding more. Cool in the pan for 30 minutes, then invert onto a wire rack to cool completely. Drizzle with Tangy Lemon Glaze.

- Tangy Lemon Glaze Combine 2 cups sifted powdered sugar and 3-4 tablespoons freshly-squeezed lemon juice. Stir until sugar is dissolved. Spoon over cooled cake.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 10, 2010 | Entrepreneurs

I was hanging out in East Austin as Black History Month drew to a close when I happened upon a series of banners hanging around historic venues. The proud displays featured the names and pictures of local African Americans who had accomplished great things in various careers — from engineering and medicine to education and the arts. As you might have already guessed, women in the food industry were not included.

That is what makes antebellum African American cookbooks such an important and fascinating discovery for me. During Reconstruction, ex-slaves like Lucille Bishop Smith, Flossie Morris, and Mary Bernon were adding entrepreneurial skills to their culinary proficiency, but their work was unknown beyond the tiny communities in which they lived.

A former slave named Abby Fisher also established a reputation for excellence in cookery and business along the shores of the Pacific, but she did something extraordinary for the time: She published a cookbook to prove it. So did Malinda Russell, a free woman of color.

Although unschooled, Fisher operated a pickles and preserves manufacturing business with her husband, Alexander in San Francisco. She won awards and medals at various fairs in California. And in 1881 she released What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, a collection of more than 150 recipes – “a book of my knowledge, based on an experience of upwards of 35 years in the art of cooking.”

Fisher’s trailblazing cookbook bears witness to a legacy of excellence among black cooks, and to her hidden heritage of African-inspired dishes, including several for okra and black-eyed peas, gumbo, and jambalaya – noteworthy on any day, but exceptionally so during the prickly era of national reform in which she lived.

The Historical Notes in the Afterword to What Mrs. Fisher Knows, historian Karen Hess tells us why, in these tough economic times, we need to remember Abby Fisher: “She was clearly a remarkably resourceful woman, one of those strong matriarchal types who kept their families together under the most adverse circumstances.”

Malinda Russell’s A Domestic Cook Book: Containing Useful Receipts for the Kitchen, was a fragile, 40-page collection, printed in 1866 in Paw Paw, Michigan, before the Longone Center for American Culinary Research at the University of Michigan reproduced it. I was blessed to be part of the process, introducing Malinda to her first audience, and reminding them that this collection also teaches us how to use cooking to manage scarce resources.

In her brief autobiography, this free woman of color tells us a great deal about herself – a stark contrast to Fisher’s contrite spirit, and surprising considering the post-Civil War tensions of the time. She was a hard-working, single mother, a business owner, and the ladies of the community esteemed her.

Including their words of endorsement in her preface made good business sense, but we also can see the gesture as a measure of her integrity. Russell acknowledged everyone responsible for her talent and her project – an unusual action in light of the out-and-out plagiarism that was common practice among her publishing contemporaries. She said she apprenticed under the tutelage of Fanny Steward, a colored cook of Virginia, that she followed “the plan of The Virginia House-Wife,” and attribution accompanied several of her prescriptions.

Together, this free woman, Fisher, and to some extent the male authors of house servants’ guides, corroborate the notion of culinary literacy among black cooks. The modest collections of these masterful authors did for the art of African American cooking what Amelia Simmons’s little book did to distinguish the American cooking style from English cookery in 1796: They are like a culinary Emancipation Proclamation for black cooks.

*

Abby Fisher’s recipe for “Jumberlie — a Creole dish,” is a masterpiece of simplicity. It relies on farm-fresh chicken, smoked ham, and what she calls “high seasoning.” I’ve adapted her dish for modern kitchens, adding shrimp and sausage to the mix for a hearty one-pot meal. Serve it with crusty French bread and a cool crisp salad, and then wonder, as I do with every bite what delicacies the other women of the time might have left us if they had the means, time and resources to do so.

In Her Kitchen

Jambalaya

Ingredients

- 5 slices bacon, diced

- 1 onion, diced

- 1 green pepper, diced

- 1 stalk celery, diced

- 1 tablespoon minced garlic

- 3/4 teaspoon dried thyme

- 1 1/2 cups uncooked rice

- 1 cup diced tomatoes

- 3 cups chicken broth

- 1 bay leaf

- 1/2 pound smoked ham or sausage

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 teaspoon cayenne pepper

- 1/2 pound shrimp, peeled and deveined

- Hot pepper sauce

Instructions

- Fry bacon pieces in a deep skillet or Dutch oven until crisp. Remove to paper towels to drain and set aside. Add onion, green pepper, celery, garlic and thyme to the pan and saute until the vegetables are tender but still crisp. Add rice and continue to cook until the mixture is light brown. Stir in tomatoes, broth, bay leaf, ham, salt and pepper. Bring to boil, then reduce heat to simmer and cook, covered 15 minutes. Add shrimp to pan and cook 5 minutes longer or until shrimp turn pink. Adjust seasoning and serve with hot pepper sauce.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

Comments