by Toni Tipton-Martin | Nov 8, 2011 | Domestics

It is Day 3 of a quick get-away to New Orleans and I am hopping over heaving sidewalks and the mammoth roots of heritage oaks as I jog toward the urban oasis known as Audubon Park in Uptown when up ahead, of all things, I encounter The Help.

Now, instead of the calming anticipation of an escape from the Texas heat and draught, I’m a little grumpy thinking instead about the movie the New York Times described as a “big, ole slab of honey-glazed hokum.”

Again.

The problem is this: Though slightly distorted by the mist of a steamy humid morning, I can see a narrow black woman in uniform as she emerges from a dilapidated Chevy. She waves goodbye to the elder lady behind the steering wheel, makes her way up the cobblestone walk and knocks on the door of an opulent southern mansion. As I jog by, I extend morning greetings to them both and realize that while I have been straining to hear the voices of accomplished Louisiana cooks over the loud and unrelenting gaggle surrounding the record-breaking book and film, real women of color are still reporting to work in the homes of wealthy families in these “post racial” times.

That reality is one of the truths about the complex relationship between American domestic workers and their employers flooding my recent thoughts with the unrestrained fervor of floodwaters from Lake Pontchartrain. And I am not the only one thinking this stuff.

An internet title search of Kathryn Stockett’s exploration of domestic race relations revealed a diverse range of opinions, several fascinating character studies, an open letter to fans posted by the Association of Black Women Historians and a thoughtful review by Audrey Petty in the Southern Foodways Alliance newsletter that compares The Help to a historically accurate text published at the same time, by Rebecca Sharpless entitled, Cooking in Other Women’s Kitchens, Domestic Workers in the South, 1865-1960.

But, it was the broad sweep of reactions I observed at a University of Texas roundtable comprised of Austin students, community members and scholars who gathered to answer the question “What Are We Going to Do About the Help?” that galvanized my resolve to stop fretting about this tiresome fiction and do something productive: Focus on giving life to the unnamed women who really did do America’s cooking in The Jemima Code – The book.

While African American historians and critics are rightly troubled on numerous levels, white audience members seem surprised and even offended by their furor. Whichever side of the debate you are on, one reality is easy to defend: Aibiliene and Minny have stirred a race and food dialogue that gives Jemima Code cooks the opportunity to tell their own sweet, long-suffering truth not just in academia, but with empassioned Americans, too. Finally. Too bad their book won’t be on shelves in time for the holiday DVD release of the film, which is sure to prolong the negative discourse.

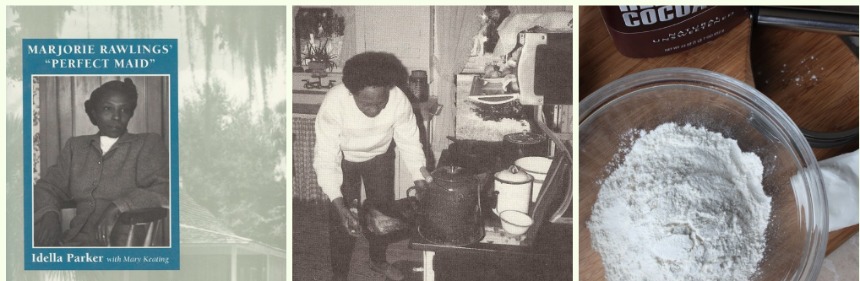

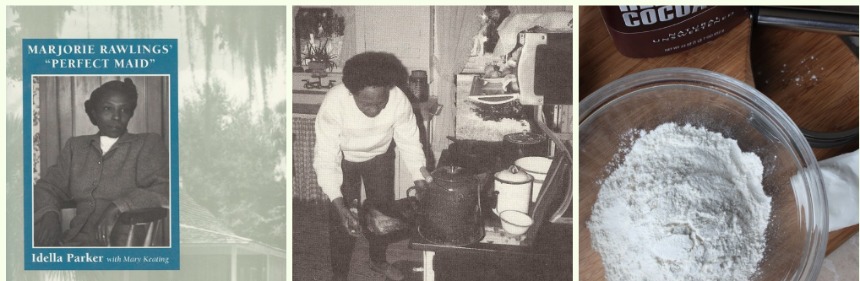

Thankfully, while we await the book, we can learn from Idella Parker.

Although her autobiography does not contain recipes in the traditional sense, Idella’s story accomplishes something unique and wonderful that continues to elude focus groups and institutional reconciliation efforts, scholarly works, well-intentioned cookbooks, and fiction like The Help with its fanciful domestic vibe. Parker draws everyone into the kitchen, inviting them to cook for each other and to persevere through awkward conversations about race when she describes what it was really like to be Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings “Perfect Maid” — a notion the Delany Sisters called, “Having Our Say.”

In 1992, at about the time that I began shopping the idea of The Jemima Code to academic and trade publishers to give voice to the unheard, this former domestic, teacher, and cook was going to press with an ambition similar to mine: telling her own account of life in the household of a popular American novelist.

“Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings called me “the perfect maid” in her book Cross Creek,” Parker wrote in the Preface to Idella, Marjorie Rawlings’ Perfect Maid. “I am not perfect and neither was Mrs. Rawlings, and this book will make that clear to anyone who reads it.”

Parker crafts an insightful look into the complex chemistry that existed between a black cook and her mistress in the late 1930s from memories that are believable, poised, and fair. As the story of their life together unfolds, we hear how it felt to be underpaid and overworked, and of Idella’s courage in the face of blatant racism.

And she is frustrated by this, also: after months together in the kitchen testing recipes for the cookbook, including many that were hers such as the chocolate pie, Idella is given credit for just three of them, including the biscuits.

Nearly 20 years later, fans still rave about Rawlings and her Cross Creek Cookery in reviews, while black cooks stare down jocular characterizations that portray them in aseptic stereotypes that trace back 100 years. In the final words of her autobiography, Idella describes the paradoxical situation like this:

“Our relationship was an unusually close one for the times we lived in. Yet no matter what the ties were that bound us together, we were still a black woman and a white woman, and the barrier of race was always there.

“In private, we were often like sisters, laughing and chatting and enjoying one another’s company. We shared many years together, helped one another through bad times, and rejoiced for each other’s happiness. Between the two of us there was deep friendship and respect, and no thought of the social differences between us.

“But whenever other people were around, the barrier of color went up automatically. Without acknowledging that we were doing so, we became more distant to one another. She became the rich, white lady author, and I became quiet, reserved, and slipped back into her shadow, ‘the perfect maid.’”

Funny thing is, with truth such as this, Parker just doesn’t come off like the kind of woman who would retaliate for bad times by putting shit in the mistress’ chocolate pie.

Would she?

In Her Kitchen

Cross Creek Chocolate Pie

Ingredients

- 1 cup milk

- 1/2 cup granulated sugar

- 1/4 cup all-purpose flour

- 5 tablespoons cocoa powder

- 1/8 teaspoon salt

- 2 eggs, separated

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- 1 (8-inch) baked pie crust

- 1/4 cup powdered sugar

Instructions

Scald the milk in the top of a double boiler. Combine the granulated sugar, flour, cocoa, and salt and whisk into the milk. Beat egg yolks lightly. Stir in the yolks and cook, stirring constantly, until the mixture is well thickened. Remove from heat and cool slightly. Stir in 1/2 teaspoon vanilla. Pour into the baked pie crust. Beat egg whites to soft peaks. Gradually beat in powdered sugar and remaining 1/2 teaspoon vanilla. Beat until stiff peaks form. Spoon meringue onto chocolate filling and bake at 325 degrees 20 minutes, or until lightly browned

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jun 19, 2011 | Uncategorized

Today is Juneteenth, the day Texas slaves learned of their freedom. It is also the last day of the exhibit I co-curated at Project Row Houses in Houston as part of a fundraising effort I lead. The schedule of events is not a coincidence; it is one more example of the renewed spiritual presence of the women of the Jemima Code who are beginning to change lives one person at a time.

Last week, friend and colleague MM Pack visited 2515 Holman for a story she is writing for Gastronomica about the installation, Round 34: Matter of Food. We agreed not to talk about the project before she went, leaving the door open for her to have her own personal experience with the women and the space. Shortly after MM’s visit, I received this text: “I sure felt a strong spirit of your ladies in that house…”

Before MM, there was another text from journalist Bob Jensen. Bob is a radical writer, who turns scrutinizing observations into provocative articles that mix questions about women’s rights, public policy with admonitions for social accountability. He had been working on a piece about my advocacy and proudly reported the title he planned to pitch to internet publishers: “The Haunting of Toni Tipton-Martin.” He admitted that during our hours together, he had been “touched” too. (Bob shared his revelation shortly after we wrapped up installation of the screenprints of the women, when, as I wrote several blogs back, my image mysteriously appeared superimposed in the enlarged photograph of the exhibit’s main character, The Turbanned Mistress.)

Between texts, there were other spooky bursts including a report from a sharp graphic designer who noticed that my initials match the abbreviation we routinely use for The Turbanned Mistress — TTM.

All things considered, I suppose I am not surprised.

Twenty years ago, when I left a prestigious job at the Los Angeles Times to begin researching the women who cooked in America’s kitchens, my then editor and friend Ruth Reichl challenged me to stand unflinchingly on the work — however unpopular or controversial. Her advice made me feel like a rabble-rouser from the 1960s — the kind of person neo-soul crooner Jill Scott calls “the queen with the nappy hair raising a fist.”

In truth, steadfast activism was essential to liberty for American slaves and each of us practice it every time we resist the black cook stereotype with our embrace of uncomfortable feelings that tear down barriers.

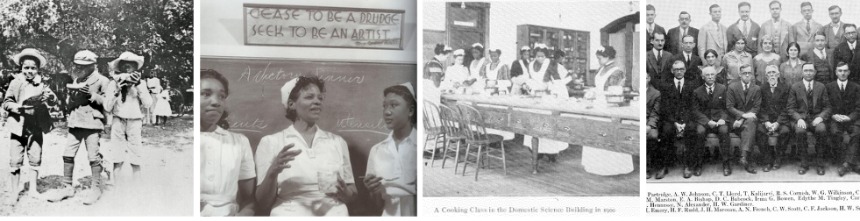

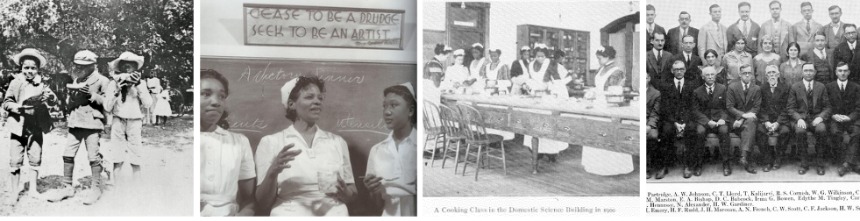

The subject came up again last week when I introduced a Mid-Atlantic audience in Philadelphia to home economics instructors, like Carrie Alberta Lyford. As director of the Home Economics School at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, and a former specialist in Home Economics for the U.S. Bureau Of Education, Lyford instilled confidence and self-determination in her students in the early 20th century and she left behind several cookbooks and leaflets to prove it.

She inspired and influenced young women while advancing the University’s mission: “…to train selected Negro youth who should go out and teach and lead their people first by example…to teach respect for labor, to replace stupid drudgery with skilled hands, and in this way to build up an industrial system for the sake not only of self-support and intelligent labor, but also for the sake of character.” But, Lyford did more than just contribute to racial uplift.

When she created curriculum and textbooks for Hampton’s Home Economics students, she left a signature on the domestic science movement that was sweeping the nation at the time. Her work reveals exactly what she valued as important lessons for students, simple advice that emphasized freshness, seasonality and quality.

To my delight, Lyford worked hard as a health and nutrition activist, with complex health insights that told former slaves that steaming vegetables is preferred to boiling to retain nutritive value, that beans provide a good meat substitute, and that raw tomatoes are most attractively served washed and skinned, without scalding. She suggested economizing with attractive cream soups made from leftover vegetables. Devoted several sections to preparing, seasoning, and garnishing meats as well as the best way to make leftovers appetizing. She recommended adding onions and spices to parboiling water to improve flavor. And, her scientific directions for properly mixing batters and doughs were thorough and easy to understand.

You could say that Lyford epitomizes what happens when community-building, and fostering self-esteem are priorities provoked in individuals first.

I love that.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | May 28, 2011 | Domestics

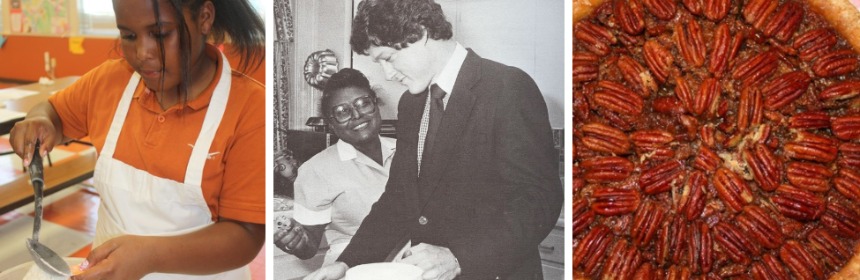

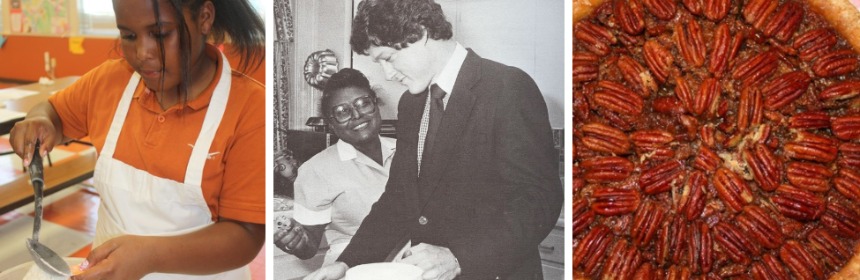

Ask the children in my Garden to Table cooking and nutrition class why we gather together daily after school, while elsewhere in the city other kids are at home watching T.V. and hanging out with friends, and these ebullient third through fifth graders will shout with confident pride: “To get healthy, not skinny!”

For about a year, as part of the WellNest at the University of Texas Elementary School, 20 students have grown and maintained organic vegetable gardens, played games that were as much fun as MarioKart, learned about the MyPyramid groups and figured out how to read food labels. They also took away a few intangible values that should help them lead healthy, productive lives defined by good character and common sense — all while cooking their own snacks from whole grains, fruits and veggies. They just didn’t know it.

So when children’s cooking instructor and cookbook author Michelle Stern and I met at the White House last summer (we were among the chefs invited to join the First Lady’s launch of Chefs Move to Schools), and she invited Garden to Table to be part of a workshop she was planning, I jumped at the chance for these kids to show off their culinary smarts and mastery of some very basic life skills. Months later, when Bill Yosses, the White House Executive Pastry Chef agreed to join the event, my meeting Michelle seemed more than serendipitous — it was Heaven sent.

Garden to Table teaches this eager bunch that there are no good or bad foods and that balance and moderation are lifetime goals they should strive to achieve. I confess to them that I too was a fat kid with an insatiable sweet tooth. I didn’t exercise very much at all. And, yet today, I live a mostly healthy life, jogging or swimming daily, passing up foods that don’t really matter that much to me, and saving my calories for goodies that I really love — like Champagne and chocolate. We also learn to respect one another while practicing table etiquette.

The prospect of introducing them to the man whose baking talents make the President of the United States just as nervous about diet as they are was, well, delicious.

Last Spring, David Axelrod, Obama’s senior advisor, told Jay Leno that the President was forced to “separate” from the White House pastry chef to break his bad eating habits. The President’s “pie problem” story was reported in the Huffington Post.

“One of the things that happened when he came to the White House is they have a very great pastry chef. It became a big problem,” Axelrod confided on “The Tonight Show.”

President Obama isn’t the first president to be taunted by the cook’s pie. During his years in the Arkansas Governor’s mansion, President Clinton felt just the same — allured by chess pie. It was made by a woman whose image hangs in the Jemima Code’s gallery of great cooks, Liza Ashley, author of Thirty Years at the Mansion.

Growing up, Ashley developed a passion for cooking while she followed her grandmother around at work on Oldham Plantation where she was born. As she matured, habits of self-control, courtesy, confidence and time management blossomed. She even led a food service team that at one point relied on inmates to get the kitchen work done.

“Ashley is an historic figure,” wrote Bill, Hilary and Chelsea Clinton, in the Introduction to the Clinton White House edition of this Classic Cookbook of Recipes, Recollections, and Photographs from the Arkansas Governor’s Mansion. “For three decades she has caused governors and their families to fight and lose battles of the bulge. Her years of service…have left their mark on history.”

Anyone who accepts the First Lady’s challenge knows that teaching kids cooking and nutrition can be rewarding and fun. It can also be a lot of work. There are bureaucracies to navigate. School budgets are limited. And, sometimes, the kids would just rather go home and play.

If Ashley could be with us on June 1 at the Kids in the Kitchen workshop, at a gathering of chefs (including Chef Bill) at the Texas State Capital, and at a fundraising Pie Social hosted by SANDE on June 4 that will honor women like Ashley, she would do more than esteem our dedication to improved lives; she would model it.

*

For information about Chefs Move to Schools at the Texas State Capitol, or the Kids in the Kitchen cooking workshop at the University of Texas Elementary School and Whole Foods Market, check out the Conference highlights at iacp.com.

To learn about The SANDE Youth Project’s preservation project and Peace through Pie, our fundraising social and Juneteenth celebration, see the events listing at: thesandeyouthproject.org.

In Her Kitchen

Bill Clinton’s Favorite Lemon Chess Pie

Ingredients

1/2 cup butter or margarine

2 cups sugar

5 eggs

1 cup milk

1 tablespoon flour

1 tablespoon cornmeal

1/4 cup freshly-squeezed lemon juice

Grated zest of 3 lemons

1 (9-inch) unbaked pie shell

Instructions

In the bowl of an electric mixer, cream together butter and sugar. Beat in eggs and milk. Beat well. With mixer running, add flour and cornmeal, alternating with lemon juice. Beat in lemon zest. Pour filling into pie shell and bake at 350 degrees for 35-40 minutes, or until center is set.

Number of servings: 8

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 28, 2011 | Kitchen Tales

A warm, gentle breeze blew across the front porch at 2515 Holman causing the screenprint of the Turbanned Mistress to sway forward and back the way your grandmother might rock her chair to and fro after worship service on Sunday afternoon. It was as if she was there, watching and listening to our every word, waiting for the just-right moment to interject a remark. Which, of course, she never did.

Although her presence was felt as the inspiration for the intergenerational, gathering of women of varying cultures and backgrounds who came together on Easter weekend to share pie and kitchen memories at Hearth House, she did just what generations of black cooks always did: She simply faded into the background.

If you’ve been reading this blog, or have ever received my business card, then you know that the Turbanned Mistress is no longer living, but I keep her image alive through words, exhibits and whatever means necessary so that women like her who worked in America’s kitchens are not forgotten. She is one of five images of African-American cooks, who will be on exhibit at Project Row Houses in Houston’s historic Third Ward for PRH’s Round 34: Matter of Food from now through June 19, Emancipation Day.

I couldn’t help but notice the irony.

There we were. On Resurrection weekend. A group of strangers, getting acquainted through the simple and common act of sharing food and remembrance. Some of those present were passionate cooks. Others were just developing their culinary courage. At least one, admitted she was not a cook at all, but she did really love to eat. Whatever the motivation, we all had at least one thing in common — our hope that this, the first in a series of Apron Strings Community Conversations, would restore cooking to its rightful place as the center of family and home, while taking down barriers and building up community one person at a time. And, simultaneously, black cooks would be re-born.

Renatta is an artist and a self-proclaimed “preserver of tradition” determined to keep memories of gardening, crabbing and cooking with family alive. She took a seat at our long table of sisterhood alongside Tahila, Luanne, Razz, Linda, and three generations of women from Lily Grove Missionary Baptist Church, who not only came to join the conversation, but agreed to be part of our oral history project with the University of Houston and Foodways Texas, which will collect stories and recipes of Texas women.

Crystal Granger, the center of the generations and an architect, described how she learned to appreciate the precision and science of cooking from her grandmother who practiced a particular kind of mise en place. The artsy side of her culinary skill, she explained, comes from her mother, Shirley. Shirley, a former teacher, now spends her days motivating seniors toward active living, employing some of the same strategies that once helped her inspire youngsters to learn. As she regaled us with her special way of coaxing reluctant seniors out of the withdrawl that can come with aging, her mastery of culinary art as an educational tool that can nurture became evident. With Crystal, Shirley, and Aunt Marva Smith as role models, it’s no wonder grand-daughter Chimere has such incredible passion for baking and a joy for living.

This coming weekend, the Granger family will be interviewed by students from the University of Houston’s Department of History. They will talk about their tea cake chronicles and the important life-skills they developed while cooking and baking together. The goal of the project is to break the Jemima Code by creating a permanent record that documents and preserves African-American culinary truth for future generations of individuals and researchers, too.

Paradoxically, if someone had bothered to interview the Turbanned Mistress and capture her testimony she would certainly have communicated a few simple anecdotes about life during slavery, but like parables, her experiential yarns would likely have revealed her secrets of emotional and physical survival under barbaric circumstances, too. And that translates into useful lessons about perseverance and discipline, tolerance and self-worth.

Linda Shearer, director of PRH put the whole process in perspective — comparing our Easter gift with the narrative artistry of John Biggers and the way he used cultural heritage and everyday experiences to change the perception of African Americans.

“Your life can be your art,” Shearer said, as the afternoon drew to a close and we all basked in the glow of new relationships defined by a shared intimacy. “We all have a creative side, but it can take a wide variety of shapes and form. What goes on here is you learn from each other.”

* * *

If you would like to join our conversation and give new life to the subject of African-American foodways, the next Apron Strings kitchen table conversation will take place at Hearth House, at Project Row Houses (projectrowhouses.org) in Houston on May 21.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 12, 2011 | Plantation Cooks

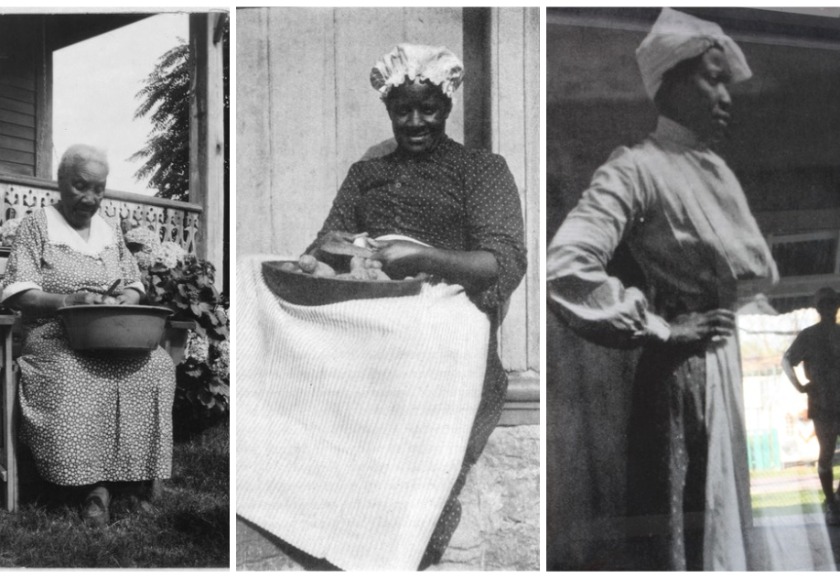

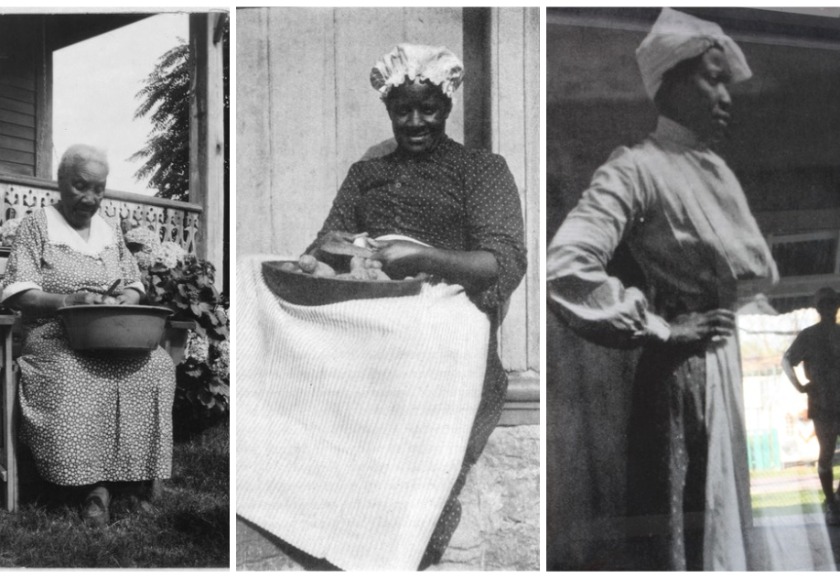

Betty Simmons sits leisurely on the back porch at 2515 Holman, in Houston’s historic Third Ward with a big, round metal pot in her lap and a curtain of voluptuous hydrangeas as her backdrop. She has a small knife in one hand, peeling what appears to be potatoes. Her white hair is brushed back away from her face, revealing a surprisingly supple and healthy look for a woman of nearly 100. The chain link of a porch swing is barely visible beyond the ornate railing.

Betty is one of five Jemima Code women who are on exhibition through June 19, at Project Row Houses, Round 34 Matter of Food. My artist friend and Peace Through Pie partner Luanne Stovall and I are co-curators of Hearth House, a traveling installation where Betty and the cooks of the Blue Grass Cook Book (the Turbaned Mistress, Aunt Frances, Aunt Maria and Aunt Dinah) are capturing the hearts of visitors just about as much as they enchant us.

Some years ago, as I fretted on a Southern Foodways Alliance excursion over the loss of these women, my friend and mentor John Egerton asked me whether they were haunting me. I shared his silly question with some artsy friends who were having their own unique, spiritual responses to the women. Before we knew it, the idea for the Project Row Houses exhibit materialized.

That phenomenal creative team (Ellen Hunt, Meeta Morrison, Luanne and I) digitized and enlarged the women’s images onto seven-foot-tall, transparent screen-like fabric that is suspended from the ceiling in one of seven shotgun-style houses at PRH.

Of course, we all knew that in order to break the code, the space had to be beautiful, so the walls were painted in warm colors that bring thoughts of sweet potatoes, sorghum and sunflowers to mind. The text is minimal — drawn from the inspirational words of Mary McLeod Bethune and from the women themselves. And, a fourth wall, painted in chalkboard paint, provides a space for the community to share kitchen memories and pie stories (which we erase periodically to symbolize the way the women were erased from history). A rough-hewn long table invites guests to linger and to leave their kitchen tales on recipe cards that will become part of our permanent archive.

When the banners were first unrolled, I actually lost my footing and crumbled onto the floor. And cried. I’d spent so many years waiting for these women to finally be honored. To top it off, on our final day of installation, my mother noticed that as I stood on the back porch of the house just beyond the screen of my favorite, the Turbaned Mistress, my silhouette was eerily superimposed into the screen like the shadow of a child, ready for tutelage at her side. Thank goodness she had the sense to photograph the moment. Obviously, the mystery of the women is very personal. And, it is palpable.

Since Opening Day, people visiting the exhibit have written to confess their experiences, too. They tell me how Aunt Frances looks over them in different ways depending upon the sunlight, or when the hot, humid breeze blows through the house at different times of day.

Is there something special to know about Betty?

Betty was one of those extraordinary slave girls, who grew up in the kitchen in the shadow of a phenomenal Texas cook who had absolutely no idea she was saving a child’s life as she passed on culinary skills casually, one meal at a time. But, she did.

Betty was born a slave to Leftwidge Carter in Macedonia, Alabama, then she was stolen as a child and sold to slave traders, who later sold her in slavery here in Texas, where her cooking skills protected her from a harsh life of field labor in slave times, and helped her manage scarce resources in freedom.

She was interviewed at a time when national pursuits – from board games and radio to mystery novels by Agatha Christie – helped Americans escape the rigors of Depression-era living, and field writers for the Federal Writer’s Project recorded the life stories and oral histories of former slaves.

Sadly, the government didn’t think to ask many questions about food and cooking, but I’m not mad at them. Fortunately for all of us, the conversational style of Betty’s narrative gives an intricately detailed look at the precarious life of a slave cook working at a Texas boarding house. I learned a little about humility, charity and self-respect from Betty. And, after months of putting the wrong things first in my life, I’m hoping she will help me get my priorities straight from today forward.

What do her words encourage you to do?

Here is a bit of her story:

When massa Langford was ruint and dey goin’ take de store ‘way from him, day was trouble, plenty of dat. One day massa send me down to brudder’s place. I was dere two days and den de missy tell me to go to the fence. Dere was two white men in a buggy and one of ‘em say I thought she was bigger dan dat,’ Den he asks me, ‘Betty, kin you cook? I tells him I been the cook helper two, three month, [Betty’s aunt Adeline was the Langford’s cook] and he say, ‘You git dressed and come on down three mile to de other side de post office.’ So I gits my little bundle and when I gits dere he say, “gal, you want to go ‘bout 26 mile and help cook at de boardin’ house?

Betty’s narrative ends with a sad revelation that her massa eventually did lose everything he owned to creditors — including his slaves. She and the remaining servants were sent to various traders — some benevolent, some harsh — in Memphis and New Orleans. Eventually, Betty the child winds up in Liberty, Texas, where she conveys a message that still resonates for for everyone trying to make it through difficult times — including me:

We work de plot of ground for ourselves and maybe have a pig or a cuple chickens ourselves…We gits on alright after freedom, but it hard at furst ‘cause us didn’t know how to do for ourselves. But we has to larn.

Comments