by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 30, 2014 | Entrepreneurs

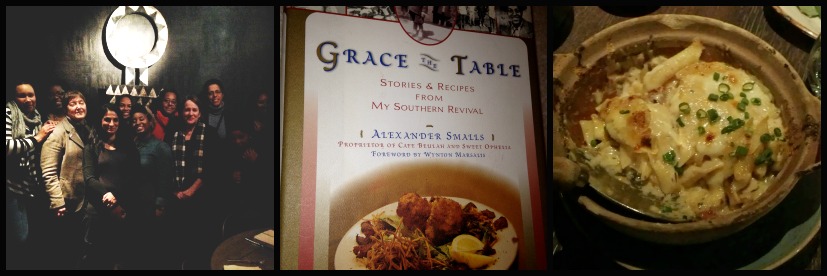

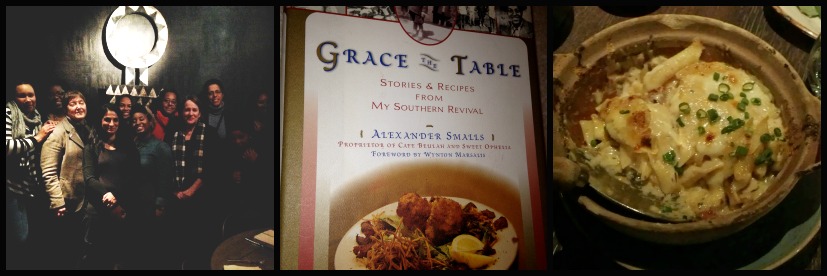

Last week on a frigid Thursday evening, I found myself in Harlem surrounded by snow drifts, a dozen Facebook food friends, and inspired Afro-Asian cuisine at Alexander Small’s sexy new restaurant, The Cecil. An ensemble of attentive waiters played their parts with aplomb in the dimly-lit dining room, recommending southern-styled cocktails and dishes that layer classic and global flavors, as we pondered what has changed for blacks in the food industry, what hasn’t and what we can do about it.

I was in New York for a meeting of the James Beard Broadcast Media Awards committee, noticeably agitated by the dearth of African American entries, and fresh off a panel in Austin on the subject of new media, women and food. My thoughts were still swirling around issues of access, increased opportunities, and competition created by the Internet, but I was absolutely delighted by this chance for kinship with talented, up and coming food industry folks who share my fascination with the African American food legacy, and the authors of The Jemima Code.

One of those enthusiasts, culinary historian Michael Twitty, was unable to join us, but he and I will continue the conversation this Saturday when we co-present History Around the Table: African American Cooks and Our Culinary History at the French Legation Museum in Austin. Twitty soared to the forefront of the foodie conscience after writing an impassioned letter to beleaguered Paula Deen and appearing on the PBS special, African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Having spent more than 30 years learning, thinking and writing about food in traditional media, I have been thrilled to celebrate its accolades for Twitty, and now for The Cecil’s Chef de Cuisine Joseph “JJ” Johnson and its opera singer-owner Alexander Smalls. That night, not even the disappointing showing among the award nominees could overshadow the essence of my optimism for the future: professional excellence, coalition building and “fusion cuisine.”

Fusion cooking is the same cultural blending practiced by our ancestors who melded European and African techniques with the indigenous ingredients of the Americas into a hallowed (southern) cuisine. Scholars have used various titles to summarize it — “African grammar,” “wok presence,” “Creolization” — but it took 1990s chefs to apply arts and music terminology to the rich exchange, and to make it stick.

Back then for example, accomplished restaurant and catering chef Jeanette Holley wore her African American fusion sensibilities like a culinary badge of honor. Born to a Japanese mother and a black father, she built her reputation on the best of what each culture had to offer. Ginger and rum spiced sweet potato pie. Asian flavors, such as star anise, coriander, and Szechwan peppercorns dusted barbecued pork spareribs. It was a glorified style that “borrowed parts from each other to develop a new language of their own,” she said in a news article for the Los Angeles Times Syndicate.

Long before there was The Cecil, the fusion way also made it possible for Smalls to blend his penchant for storytelling and his love of southern food with international flair into acclaimed restaurants and a 1997 cookbook, Grace the Table: Stories & Recipes From My Southern Revival, where Sweet Potato Waffles and Peach Cobbler hold their own alongside Sea Bass Wrapped in Lettuce Leaves and Pork Masala with Mixed Greens.

As trailblazers, all three gentlemen are obviously imaginative and talented and able to show the world what happens when we look back at historic foods and classic cooking methods with reverence, but employ them as stylish flourishes rather than remnants of poverty and survivalist cooking. And, they are living, breathing evidence of the old saying: “Attitude is everything,” whether we are talking about Twitty’s blending of Jewish and African American culinary histories, or Johnson’s Afro/Asian/American Oxtail Dumplings, Collard Green Salad, and Macaroni Cheese Casserole (accented with rosemary, caramelized shallots, and pepper ham), This is certainly good news and a sign of changing times for other aspiring men in food.

So what about women like Holley? Isn’t it time for strong young ladies to enjoy the accolades and benefits associated with artistic blending in the kitchen?

You may already know about the firestorm created by a recent Time Magazine cover story that ignored female chefs in general, but for me it renewed dialogue about the barriers to entry for black women chefs, too.

Disregarding the accomplishments of black women is not new. From the very beginning, traditional media has paid more attention to black men, publishing their recipe books in the trade, maintaining records of their careers in catering, building cooking shows around them, and crowning them with title of “chef” whether they cooked on the Pullman Railroad, on college campuses, in hotel dining rooms, or in the White House.

With new media, however, culinary honor may finally be possible for young female food professionals of color — like my dinner companions — who are standing out, and up for themselves, while promoting and supporting one another. (With encouragement from established industry veterans; thanks Nancie, June, Debbie, Michelle, Ramin and Scott.)

Therese Nelson is a graduate of Johnson and Wales who founded the website Black Culinary History to document industry diversity and provide a space for networking; Elle Simone is a freelance chef and Food Network food stylist who studied at the Culinary Academy of New York and created SheChef, a mentoring program that fosters self-confidence and excellence in culinarily-focused young women from urban settings; Nicole Taylor, a self-described “artisan candy maker, activist, social media maven,” hosts Hot Grease, a progressive food culture radio program on Heritage Radio Network; Sanura Weathers blogs about her food studies and passion for cooking at home; multi-talented, singing chef Jackie Gordon set a tasting of New York artisan chocolate makers to music in her newest show, Chocabaret; chef Nadine Nelson, a culinary educator, community activist and event planner, celebrates world cuisines on two sites, Global Local Gourmet and Epicurean Salon; and Sarah Khan, a journalist at zesterdaily.com hopes to inspire social change around local, national, regional, and global foodways as director of the Tasting Cultures Foundation.

As our evening at The Cecil drew to a raucous close, several of these active “next generation” women leaned in with deep emotion and described her own sense of ambition and dedication sparked by Jemima Code authors — women (mostly) and some men — who lived, worked, and achieved success in the media’s culinary shadows.

My heart filled with hope that someday soon more women of color will be counted among culinary royalty and perhaps win awards for what we accomplish in new and traditional media — or bricks and mortar.

In His Kitchen

Shrimp Paste with Hot Pepper

Ingredients

- 1/2 pound large shrimp, peeled, deveined, and poached

- 1/2 cup black-eyed peas, cooked

- 1/2 cup chickpeas, cooked

- 3 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 jalapeño pepper, minced

- 1/2 teaspoon cayenne pepper

- Juice of 4 lemons

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 cup mayonnaise

- 1/4 cup cilantro, chopped

- 3/4 cup olive oil

Instructions

Place all ingredients except olive oil in a large bowl of a food processor. Pulse until smooth. With machine running, pour in olive oil and pulse until thickened. Check seasoning. Serve in a medium-sized bowl, accompanied by a breadbasket.

Makes 8 Servings

From Grace the Table: Stories & Recipes From My Southern Revival, by Alexander Smalls

In His Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 15, 2014 | The Modern Kitchen

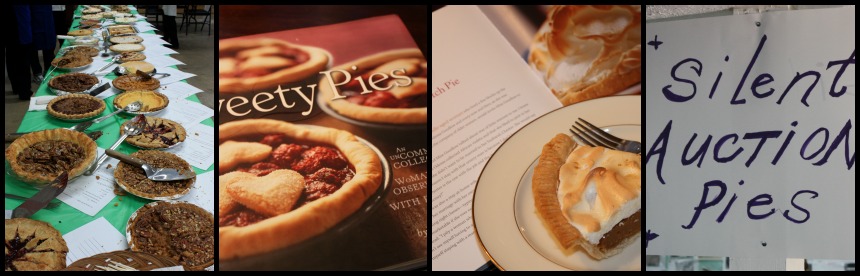

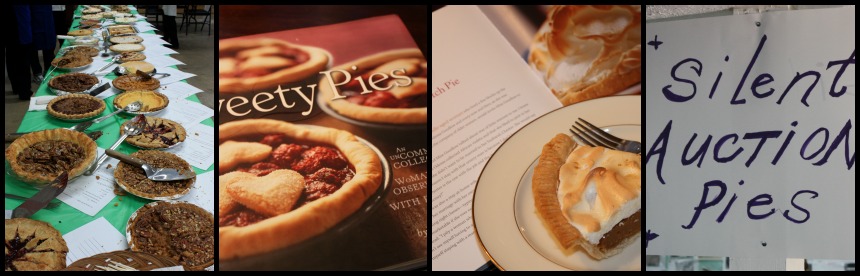

This Saturday, after four years of sharing the message that pie is a perfect food tradition for Martin Luther King Jr. holiday in other people’s churches, I get to celebrate with a Peace Through Pie social and my home congregation. I am thrilled that Round Rock has joined more than two dozen local organizations and schools in Central Texas, and a growing list of PTP hosts nationwide, but it is going to be a very full day.

It all starts with the Women and Food Symposium at the University of Texas – Austin’s Food Lab, where I am on program with several noted women, including award-winning writer and author Laura Shapiro and New York Times writer Kim Severson. Then, I will introduce Peace Through Pie, which is re-kindling the pie social to spark social change, to marchers in the 27th Annual MLK walk and program in Round Rock, Texas. (The march begins at 1:30 at C D Fulkes Middle School and ends at the Allen R. Baca Senior Center.)

The celebration at Faith4Life Church wraps up my evening with music, a pie baking contest, and a recitation to honor the 50th anniversary of Dr. King’s “I Have A Dream” speech. Pastor Evan Black and his wife Minister Priscilla invited the congregation and neighbors to come together to share sweet and savory world pies to honor Dr. King’s message of unity and “beloved community,” because Pastor Black says, “Community and diversity are my passions.”

Pastor Black was immediately drawn to the idea of mixing food, fellowship and fence-mending. The husband and father of two bi-racial sons grew up in Atlanta in a family dedicated to equality, diversity, and racial reconciliation. Although his grandfather once refused to allow his mother to attend integrated schools, she stood up for her beliefs, joined the Direct Action campaign, and marched with Dr. King, making diversity “important to me,” Pastor Black explains.

“I really want this to be an event that is open to the community. We are a church, but we want to work with, embrace, and help the community. We want to be part in any way we can. Heaven is not going to be all white or all African American or all Hispanic. It’s going to be a mixed; that’s the way the congregation should be.”

With all of this — plus tastebuds that are still sticky from the sweetness of traditional holiday pies like pumpkin, sweet potato and pecan — I needed a simple pie recipe that would go together fast, but taste deliciously different. I turned to “the ladies” of The Jemima Code, of course, and settled on a book that seemed particularly appropriate for the occasion: Colorful Louisiana Cooking in Black and White.

In a hilarious take the authors, Ethel Dixon and Bibby Tate, attempt to resolve for modern audiences the persistent confusion between southern and soul food by putting the letter “W” next to the recipe title for dishes cooked the way white folks do it and a “B” to show how we roll. Interestingly, some clear distinctions were noticeable, such as the addition of water in the “white” version of a recipe and milk on the “black” ingredients list. This book was a joy to read, but I like my friend and cookbook author Nancie McDermott’s solution better.

She ignored it.

Each little narrative in her cookbook, Southern Pies, shares folklore or teaches pie-making techniques. Nancie also attributes the recipes to their source, many of whom are Jemima Code authors, including Minnie C. Fox and her Blue Grass Cook Book, which I brought back to life in 2005. Nancie’s work does not depend upon labels. She offers no categories or stereotypes. The habit of marginalizing the contributions of African Americans simply does not exist here. This is a great collection of diverse recipes that span the southern pie pantheon giving credit where credit is due — without racial borders.

Butterscotch Pie, for example can be traced to the earliest cookbooks by both African American and white cookbook writers, sometimes called Caramel Pie or Brown Sugar Pie. In her 1948 cookbook, A Date With A Dish, Freda DeKnight cooks brown sugar, butter, and eggs with milk and a bit of flour before baking for a light and moderately sweet dessert with a hint of butterscotch flavor. Patty Pinner updates the formula in Sweetie Pies: An Uncommon Collection of Womanish Observations, with Pie, offering two versions. One follows DeKnight’s lead, making butterscotch from scratch. The other one cuts preparation time and effort by eliminating the milk, stirring the ingredients together, then finishing the pie in the oven, taking its carmel notes from butterscotch chips.

With so many choices, I’m still uncertain which one I will share this weekend to honor the birthday of Dr. King. What kind of pie will you bake?

Faith4Life church is located at 1000 McNeil Rd. Round Rock, Texas, 78681. For a complete listing of Peace Through Pie socials visit: peacethroughpie.org

In Her Kitchen

Patty Walker’s Easy Nut and Chips Pie

Ingredients

- 1/2 cup (1 stick) unsalted butter, softened

- 1 cup sugar

- 1/2 cup all-purpose flour

- 2 large eggs

- 1 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 1 cup coarsely chopped pecans

- 1 cup semisweet chocolate chips

- 1/2 cup butterscotch chips

- One (9-inch) unbaked pie crust

Instructions

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. Combine the butter, sugar, flour, eggs, and vanilla in a large bowl and beat until blended well with an electric mixer. Stir in the pecans, chocolate chips, and butterscotch chips. Pour the filling into the pie crust. Place in the oven and bake until the crust turns golden, about 40 minutes. Let cool completely on a wire rack before serving. You can dress up each slice with a spoonful of vanilla ice cream or fresh whipped cream.

Recipe from Patty Pinner’s Sweetie Pies: An Uncommon Collection of Womanish Observations, with Pie.

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 6, 2014 | Uncategorized

I am so excited.

After two years of writing, The Jemima Code – The Book is finally in production at the University of Texas Press. We are hoping for a fall 2015 release, with pop-up exhibits of photographs from the book planned as part of my book tour. In the meantime, I am working on a second book for The Jemima Code series and have re-dedicated this space to sharing my experiences as I cook with and learn from the African American cookbook authors of my rare collection and more.

My son and I are still tinkering with the layout for this journal, but my hope is that this space becomes a place where we exchange ideas about food and cooking — sharing tips, solutions, tools, gadgets, and resources — as we re-imagine the modern African American kitchen together.

Can’t hardly wait!

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 11, 2012 | Entrepreneurs, Featured

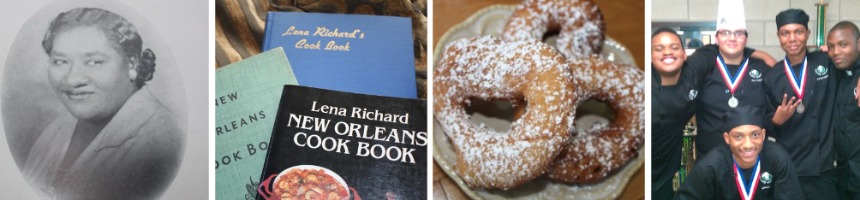

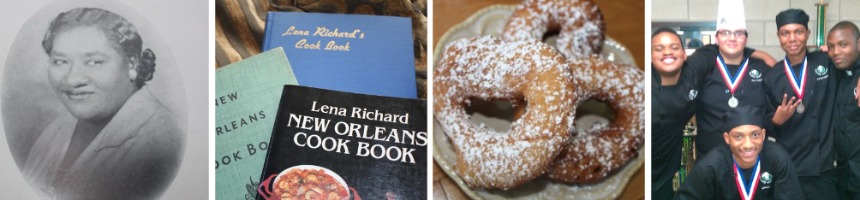

I went to the safe to retrieve a New York-area author from the Jemima Code cookbook collection to be among the black cooks featured in my pop-up art exhibit at the Greenhouse Gallery at James Beard House in Manhattan. I came out with New Orleans chef Lena Richard. More than 70 years ago, the “father of American cuisine” had been Richard’s advocate. Now, she would return to his home to uplift and encourage a whole new generation.

Until recently I had only briefly studied Richard’s life. I read in a resume of her accomplishments in the exhibition guide at Newcomb College Center for Research on Women at Tulane University, that she was a formally trained culinary student, completing her education at the Fannie Farmer Cooking School in Boston. She ran her own catering company for ten years, operated several restaurants in New Orleans, including a lunch house for laundry workers, cooked at an elite white women’s organization, the Orleans Club, opened a cooking school, and taught night classes while compiling her cookbook.

In 1939, she self-published more than 350 recipes for simple as well as elegant dishes in Lena Richard’s Cook Book. Her smiling face radiates from the kind of ladylike portrait one might expect to find cradled inside a gold locket worn close to the heart. A year later, at the urging of Beard and food editor Clementine Paddleford, Houghton Mifflin published a revised edition of her work. This book, however, contained a new title and preface, and that precious cameo-style photograph was gone.

Through the end of April, visitors to Beard House were welcomed into the sanctuaries of unsung culinary heroes like Richard. Screen-printed images of black women at work in and around the kitchen hearth in slave and sharecropper’s cabins, gardens, and in shotgun houses throughout the south hung on the walls of the Greenhouse. The images in this engaging visual history were taken from my historic reprint of a 1904 classic cookbook, The Blue Grass Cook Book — photographs that document culinary contributions to American cuisine and establish an enduring legacy for the women as modern role models who encourage everyone to cook and share real food.

In these times of Top Chef-styled plates where food is stacked, foamed and streaked, it can seem impossible to be impressed by the simplicity of three-course menus comprised of dishes like avocado cocktail, buttered saltines, broiled steak, petit pois, and watermelon ice cream — but we should try.

So, in celebration of the hard-working, nimble chef who taught culinary students how to make homemade vol-au-vent and calas toud chaud while tutoring her daughter in the entrepreneurial skills of business 101, and as part of my outreach to vulnerable children in Austin, and in partnership with the James Beard Foundation, the University of Texas, the Texas Restaurant Association, and Kikkoman, four high school culinary students cooked for a reception featuring chef Scott Barton, April 1 at the Beard House.

For the past three years, students from Pflugerville’s John B. Connally High and Austin’s Travis High have demonstrated professionalism, self-awareness, and pride in the presence of these art works, the kind of outcomes we can expect when we provide culturally-appropriate experiences that engage and inspire kids toward careers in the food industry — whether those jobs are in food archaeology, anthropology, food service, or public health.

Ryan Johnson, a senior at Connally described the meaning of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity this way: “Most people my age have never heard of the James Beard Foundation, or the IACP, but as soon as Chef mentioned those names, I couldn’t believe my ears. I thought. “No way!

“Every night this week, I could hardly sleep because of the anticipation, and thoughts of the different people I’ll meet, and foods I’ll see. My mom always wanted me to be as passionate about food as she is; her wish has come true. I am truly grateful for the wonderful opportunities my passion and hard work have brought me, and I can’t help but think, “I’m actually going to be a chef…”

For information about The Jemima Code exhibit at the James Beard House Greenhouse Gallery, visit:

http://www.jamesbeard.org/index.php?q=greenhouse_gallery

In Her Kitchen

Lena’s Doughnuts

Ingredients

- 2 cups sifted flour

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon each ground nutmeg and cinnamon

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1 egg, well beaten

- 1 tablespoon melted butter

- 1/2 cup milk

Instructions

Sift flour once, measure, add baking powder, salt, nutmeg and cinnamon. Sift together, three times. Combine sugar and egg; add butter. Add flour, alternately with milk, a small amount at a time. Beat after each addition until smooth. Knead lightly 2 minutes on lightly-floured board. Roll 1/3-inch thick. Cut with doughnut cutter. Let rise for several minutes. Fry in deep, hot fat until golden brown. Drain on unglazed paper. Sprinkle with powdered sugar, if desired.

Number of Servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 13, 2012 | Community Cooks

Yesterday morning, just before we went on the air to invite everyone, everywhere to honor the Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday by serving “Peace Pie,” my friend and partner Luanne Stovall revealed to the staff and guests at KAZI radio in Northeast Austin the warm, golden-brown, homemade apple pie she had tucked inside a shallow Steve Madden shoe box. Mouths were watering. By the end of our time with Dora Robinson on the Soul Vibrations show, eyes were watering, too.

Our movement to establish a food tradition that honors the legacy of Dr. King and his passion to build the “Beloved Community” unifies in greater ways than other holiday food traditions like Thanksgiving turkey, Christmas cookies, Valentine chocolates and Easter ham. And, it has begun catching on in cities across the nation — from Austin, New York, Chicago, Houston, and Cleveland, to Seattle and Utah.

Maybe it is because Peace Through Pie socials are inspired by the Jemima Code women who for generations brought people together at the table to solve problems, salve wounds, and uplift communities. From their pulpits at the kitchen table, African-American women practiced servant leadership. As agents of reconciliation, they quietly and subtly brought people of diverse backgrounds together at the table in southern homes and restaurants to enjoy their good cooking. But unlike the fictional women of the bestselling book and film “The Help,” who served poop-laced pie with the intent to harm, Jemima Code women baked and served pies filled with love. These role models encourage Americans to serve pie with the intention of cultivating peace and harmony at the table by making room for all and respecting every voice.

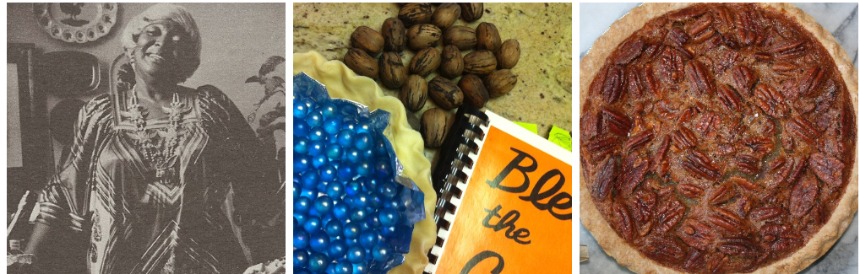

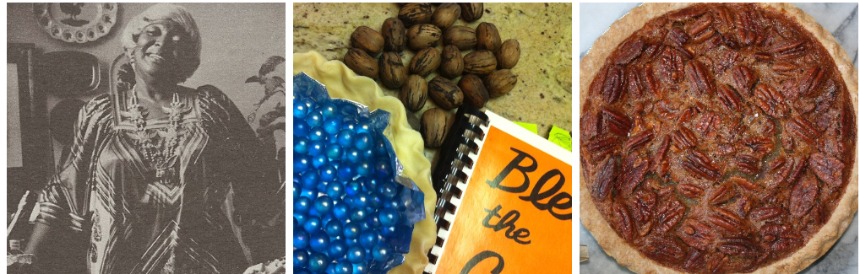

Cookbook author, caterer and community servant Bessie Munson is one of those remarkable women. Munson was raised on her grandparents’ farm near Bartlett, Texas, where the food was always plentiful and sumptuous, she says in her 1978 cookbook, Bless the Cook. She taught cooking classes in Arlington and wrote fondly of the memory of festive and wonderful gatherings around the family table… and of all the “bountiful and beautiful meals that became the reflection of a happy outgoing lifestyle in which anything can be achieved when you share and reach out to others.” In her book, she illustrates the proper way to crimp pie crust to make the edges beautiful, along with several pie recipes, including one for perfect crust.

Why reach out with pie? For three reasons: You don’t have to be a great cook or spend all day in the kitchen preparing an entire meal; Pie is universal, symbolizing inclusiveness with its round shape and diverse ingredients — whether sweet or savory, sugar-free, or gluten-free. It comes in many shapes and sizes from around the world — Latin empanadas, Indian samosas, Italian calzones and pizza pies, Jamaican and Ethiopian meat pies, British and Aussie pies, Greek spinach pie, even Asian dumplings. Finally, “Peace Pie” provides nourishment for heart and soul, creating Beloved Community and enacting Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s message of hope, equality and social justice with a food he reportedly really enjoyed (simple recipes are everywhere on the web and on the back of the bottle of Karo Syrup).

On Jan. 18, 1986, when President Ronald Reagan signed Proclamation 5431 establishing the first MLK Day, he encouraged “…all Americans of every race and creed and color to work together to build in this blessed land a shining city of brotherhood, justice, and harmony. This is the monument Dr. King would have wanted most of all.”

As I left the station, I reflected on the conversation about Peace Through Pie and the multiple ways that sharing a piece of fresh-baked Peace Pie with a family member, friend or neighbor is an enduring recipe for an edible monument. It reminds us year after year to follow Munson’s lead by reaching out to others. This weekend, as you put down social and political weapons and break down generational, race and gender differences to honor Dr. King, why not gather the ingredients for your own edible monument, craft them with your heart and hands, and share with a friend.

To learn more about hosting a Peace Through Pie social or to see a listing of Peace Through Pie Socials in your community, visit www.peacethroughpie.org.

Comments