by Toni Tipton-Martin | Nov 8, 2011 | Domestics

It is Day 3 of a quick get-away to New Orleans and I am hopping over heaving sidewalks and the mammoth roots of heritage oaks as I jog toward the urban oasis known as Audubon Park in Uptown when up ahead, of all things, I encounter The Help.

Now, instead of the calming anticipation of an escape from the Texas heat and draught, I’m a little grumpy thinking instead about the movie the New York Times described as a “big, ole slab of honey-glazed hokum.”

Again.

The problem is this: Though slightly distorted by the mist of a steamy humid morning, I can see a narrow black woman in uniform as she emerges from a dilapidated Chevy. She waves goodbye to the elder lady behind the steering wheel, makes her way up the cobblestone walk and knocks on the door of an opulent southern mansion. As I jog by, I extend morning greetings to them both and realize that while I have been straining to hear the voices of accomplished Louisiana cooks over the loud and unrelenting gaggle surrounding the record-breaking book and film, real women of color are still reporting to work in the homes of wealthy families in these “post racial” times.

That reality is one of the truths about the complex relationship between American domestic workers and their employers flooding my recent thoughts with the unrestrained fervor of floodwaters from Lake Pontchartrain. And I am not the only one thinking this stuff.

An internet title search of Kathryn Stockett’s exploration of domestic race relations revealed a diverse range of opinions, several fascinating character studies, an open letter to fans posted by the Association of Black Women Historians and a thoughtful review by Audrey Petty in the Southern Foodways Alliance newsletter that compares The Help to a historically accurate text published at the same time, by Rebecca Sharpless entitled, Cooking in Other Women’s Kitchens, Domestic Workers in the South, 1865-1960.

But, it was the broad sweep of reactions I observed at a University of Texas roundtable comprised of Austin students, community members and scholars who gathered to answer the question “What Are We Going to Do About the Help?” that galvanized my resolve to stop fretting about this tiresome fiction and do something productive: Focus on giving life to the unnamed women who really did do America’s cooking in The Jemima Code – The book.

While African American historians and critics are rightly troubled on numerous levels, white audience members seem surprised and even offended by their furor. Whichever side of the debate you are on, one reality is easy to defend: Aibiliene and Minny have stirred a race and food dialogue that gives Jemima Code cooks the opportunity to tell their own sweet, long-suffering truth not just in academia, but with empassioned Americans, too. Finally. Too bad their book won’t be on shelves in time for the holiday DVD release of the film, which is sure to prolong the negative discourse.

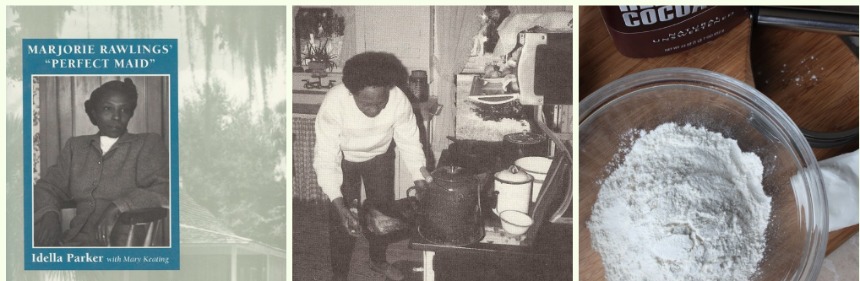

Thankfully, while we await the book, we can learn from Idella Parker.

Although her autobiography does not contain recipes in the traditional sense, Idella’s story accomplishes something unique and wonderful that continues to elude focus groups and institutional reconciliation efforts, scholarly works, well-intentioned cookbooks, and fiction like The Help with its fanciful domestic vibe. Parker draws everyone into the kitchen, inviting them to cook for each other and to persevere through awkward conversations about race when she describes what it was really like to be Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings “Perfect Maid” — a notion the Delany Sisters called, “Having Our Say.”

In 1992, at about the time that I began shopping the idea of The Jemima Code to academic and trade publishers to give voice to the unheard, this former domestic, teacher, and cook was going to press with an ambition similar to mine: telling her own account of life in the household of a popular American novelist.

“Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings called me “the perfect maid” in her book Cross Creek,” Parker wrote in the Preface to Idella, Marjorie Rawlings’ Perfect Maid. “I am not perfect and neither was Mrs. Rawlings, and this book will make that clear to anyone who reads it.”

Parker crafts an insightful look into the complex chemistry that existed between a black cook and her mistress in the late 1930s from memories that are believable, poised, and fair. As the story of their life together unfolds, we hear how it felt to be underpaid and overworked, and of Idella’s courage in the face of blatant racism.

And she is frustrated by this, also: after months together in the kitchen testing recipes for the cookbook, including many that were hers such as the chocolate pie, Idella is given credit for just three of them, including the biscuits.

Nearly 20 years later, fans still rave about Rawlings and her Cross Creek Cookery in reviews, while black cooks stare down jocular characterizations that portray them in aseptic stereotypes that trace back 100 years. In the final words of her autobiography, Idella describes the paradoxical situation like this:

“Our relationship was an unusually close one for the times we lived in. Yet no matter what the ties were that bound us together, we were still a black woman and a white woman, and the barrier of race was always there.

“In private, we were often like sisters, laughing and chatting and enjoying one another’s company. We shared many years together, helped one another through bad times, and rejoiced for each other’s happiness. Between the two of us there was deep friendship and respect, and no thought of the social differences between us.

“But whenever other people were around, the barrier of color went up automatically. Without acknowledging that we were doing so, we became more distant to one another. She became the rich, white lady author, and I became quiet, reserved, and slipped back into her shadow, ‘the perfect maid.’”

Funny thing is, with truth such as this, Parker just doesn’t come off like the kind of woman who would retaliate for bad times by putting shit in the mistress’ chocolate pie.

Would she?

In Her Kitchen

Cross Creek Chocolate Pie

Ingredients

- 1 cup milk

- 1/2 cup granulated sugar

- 1/4 cup all-purpose flour

- 5 tablespoons cocoa powder

- 1/8 teaspoon salt

- 2 eggs, separated

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- 1 (8-inch) baked pie crust

- 1/4 cup powdered sugar

Instructions

Scald the milk in the top of a double boiler. Combine the granulated sugar, flour, cocoa, and salt and whisk into the milk. Beat egg yolks lightly. Stir in the yolks and cook, stirring constantly, until the mixture is well thickened. Remove from heat and cool slightly. Stir in 1/2 teaspoon vanilla. Pour into the baked pie crust. Beat egg whites to soft peaks. Gradually beat in powdered sugar and remaining 1/2 teaspoon vanilla. Beat until stiff peaks form. Spoon meringue onto chocolate filling and bake at 325 degrees 20 minutes, or until lightly browned

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 6, 2010 | Plantation Cooks

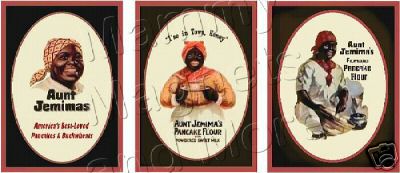

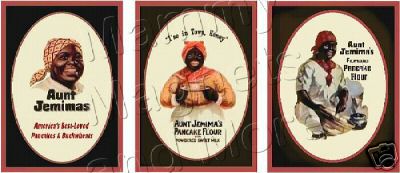

Scholars tell us that Aunt Jemima was the professional persona for household slave women generically identified in literature and history as the plantation Mammy. They say that this obsession with mythical mammies obscured the work of real southern domestic servants, making them little more than a figment of the romantic imaginations of southerners, concocted from a recipe based on “not one truth but a variety of truths and lies told by different people in different circumstances at different times for different reasons.”

In order to break the Jemima Code and find a place for African American women at the long table of American culinary history, I had to forget this kind of academic wrangling about whether mammy ever existed, and instead fill in the mammy outline with clues from multiple sources, including the writings of slaveholding families, because they are the ones who left written documentation of food experiences and practices — even though slaveholding families did not make up the majority in early America.

Interestingly, when these women registered their thoughts, emotions and opinions in their diaries, household journals and letters to family and friends the writings contained few references to meal preparation except as part of the daily routine of plantation living. They state that household slaves were assigned various domestic duties as cooks, laundresses, seamstresses, nurses, and housekeepers. They dressed in the clothes of the family. Ate better food than field slaves. Received medical treatment, and some learned to read and write, despite prohibitive slave codes that prohibited educating them.

When the mistress said, “I planted 60 acres of oats today,” she usually meant she supervised the day’s agricultural chores, not that she actually did the work herself. And, according to her texts, “Chloe,” “Aunt Rachel,” and “Mammy” all cooked. By the time the mistress’s ruminations appeared on the pages of southern ladies literature, Chloe and Rachel’s contributions, their character traits, and identity fuse into one larger-than-life, simplified woman named Mammy. And, in fiction, Mammy did everything.

Mammy affirmed the abolitionists’ stance that slavery was bad while she maintained the segregationists’ view of social hierarchy. Post-Reconstruction Mammy, reflected the new social order, too. She consoled desperate housewives, assured neophyte cooks with creative ingenuity, and at the same time was the source of America’s increasing servant problem. Mammy defended the homestead. Mammy saved the baby. Mammy trained the children, and on occasion, the Misses. Mammy cooked from memory. Mammy made the best pancakes. And, Mammy set a table that invited everyone to come.

She inspired a “Mammy craze,” which swept the nation, between the 1890s and the 1920s, says Cheryl Thurber. In 1923, the United Daughters of the Confederacy demanded that a monument to Mammy be erected in her memory at he nation’s capital. And, in 1924, a New York shop window advertised a fascinating new style for women: an audaciously colored scarf, ‘the Paris version of mammy’s old Southern bandana.”

If we only think about an African American cook’s lowly station of life, the minimal culinary contributions credited to her by historians and cookbook writers, and the exaggerated and distorted pictures used to misrepresent her intelligence, then it is, of course, impossible to believe that she could have been anything more than a simple laborer.

Fortunately, there is an alternative view.

In 1938, Eleanor Ott published a fanciful collection of New Orleans-styled recipes, entitled Plantation Cookery of Old Louisiana, which illustrates the degree of specialization and expertise known among black cooks. In it, Ott details her grandmother’s vast “culinary plant” with its numerous adjunct buildings and “mammies” assigned to each house. At Fair Oaks Plantation, Kitty Mammy managed the vegetables and herb garden and Becky Mammy was the “high priestess of the milk-house,” while “some colored sub-cook was only too pleased to sit for eight hours…to keep an eye on a kettle of simmering pot-au-feu.”

The Culinary Institute of America’s programs catalog might define these “Mammy” tasks in a more professional way, with Kitty, Becky, and the no-named Mammy each as technicians of Vegetarian Cooking: Strategies for Building Flavor; Baking and Pastry; and Soups, Stocks and Sauces.

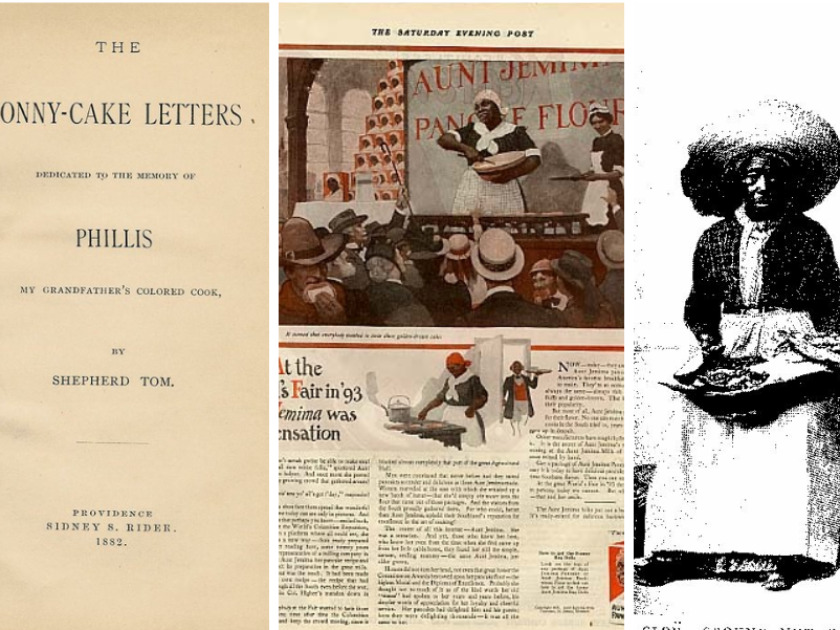

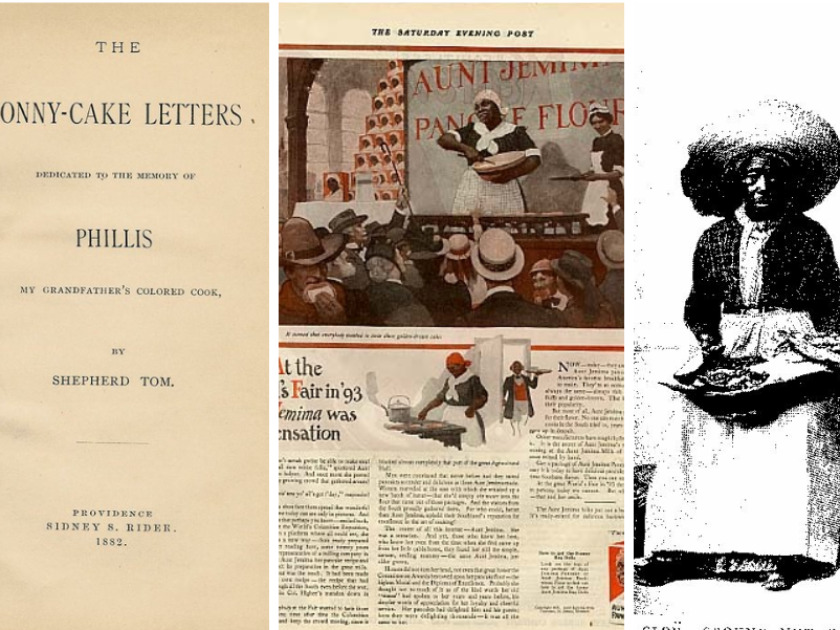

And, then there is, The Jonny-Cake Letters, Dedicated to the Memory of Phillis My Grandfather’s Colored Cook, a journal written in 1882 by Thomas R. Hazard of Rhode Island. Phillis is Hazard’s muse. She is “universally admired.” Is the “remote cause of the French Revolution and the death of Louis 16th and Marie Antoinette.” And, she reportedly bakes the most seductive jonny cake Hazard has ever tasted. Within Hazard’s exaggerated family tales are more than a few observations of Phillis’ culinary proficiency, which are so deeply enmeshed with his food recollections it is difficult to tell which comes first: his love of food or his passion for the skill of Phillis.

And, it really does not matter.

Phillis’ jonny cake “made one’s mouth water to look at it,” her assorted rye breads were “prized above rubies,” and this woman known only as his grandfather’s old kitchen cook from Senegambia or Guinea, was as an “artist” capable of inspiring others while tending the pot.

Like the assorted mammies of Fair Oaks plantation, Phillis’ culinary talents give the black cook’s shadows some substance, and there is evidence associating Mammy characteristics with real black cooks found in black sources, as well.

In slave culture, Mammy was a common name for mothers, and elders were addressed as “Aunty,” “Mauma and “Maum,” or “Mammy” as a mark of respect, not kinship. In the 1880 census the mythical Aunt Jemima is linked to at least one real, living African American woman, a black female servant who lists “cook” as her occupation and Mother Jemima as her name. The name Jemimah implied blessings and a message of hope, not subservience, according to Old Testament Scripture found in Job 42:12-14, and slaves, evidently knew it.

So, I am not at all surprised that legendary cooks and ex-slaves with a worthy name were brought to life in a marketing campaign created by a couple of guys trying to sell more pancake flour.

Are you?

In Her Kitchen

Whole Wheat Pancakes

Ingredients

- 2 cups whole wheat flour

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- 2 eggs

- 2 cups buttermilk

- 6 tablespoons unsalted butter

Instructions

- Whisk together the flour, baking powder, soda, salt and sugar. In a separate bowl, combine the eggs, buttermilk and 4 tablespoons butter. Make a well in the center of the dry ingredients and pour in the liquid ingredients. Stir together until just mixed. Batter will be lumpy. Heat a nonstick griddle over medium-high heat. Brush lightly with remaining 2 tablespoons butter, and using a 1/4 cup measure, ladle batter onto griddle for each pancake. Reduce heat to medium and bake pancakes until the top is bubbly and the edges begin to crisp, about 2 minutes. Using a wide spatula, turn pancakes over and cook on other side 1 minute longer. Do not flatten pancakes. Remove to serving platter and keep warm. Wipe griddle with paper towels, then repeat process with remaining butter and batter.

Number of servings: 4

In Her Kitchen

Comments