by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 27, 2015 | Featured, Uncategorized

This will be the last regular post for The Jemima Code — a blog that turned the spotlight on America’s invisible black cooks and their cookbooks, grew into a traveling exhibit and book available now via the University of Texas Press and spawned a 501c3 nonprofit organization. Three new initiatives, inspired by current events, will take its place.

Over last year’s Thanksgiving weekend, an MSNBC segment with Melissa Harris-Perry shifted attention from outrage and protests over racial profiling in Ferguson, Mo. to racial stereotyping in the food world. The topic of discussion: food, race and identity. Using Jim Crow era imagery and ignored culinary history as the backdrop, a panel of experts introduced viewers to a surprisingly academic food justice dialogue, raising a question black food professionals wrestle with all the time:

What we can learn about who we are when we shake off the shame about how or what we eat?

The gathering included Psyche Williams-Forson, author of Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, & Power, and directed some much-needed attention to the idea of reclaiming ancestral foods as a source of cultural pride. Williams-Forson, whose illuminating scholarship examines the complex relationship between racist and realistic characterizations of our food traditions, acknowledged the destructive legacy associated with negative images of African American food choices. The insightful scholar also pointed to positive aspects of her affirming work that encourage black women to embrace the myriad ways our foremothers used food for economic freedom and independence, community building, cultural work and to develop personal identity.

Take watermelon and fried chicken for instance. Some black folks feel demonized when they eat these foods in public, while chefs in trendy restaurants all around the country earn high dollars for watermelon salad and gluten-free gospel bird. And don’t even get me started talking about the book and blog that made white authors household names when they capitalized on the label “thug” and its new meaning — symbolizing “a slice of the African American urban underclass by others privileged to define them, label them, and take their lives…,” as Michael Twitty stated, while black authors struggle to secure publishing contracts. (You’ll have to read his blog post and the comments about Thug Kitchen on Afroculinaria.com to get the scoop.)

Even with evidence pointing to valuable African American foodways, the discussion ended with frustration as MHP exclaimed: “I feel like we just need to bring joy to eating all of it.”

It was as if “nerdland’s” exasperation (MHP’s self description) parted the Red Sea, offering freedom to culinary history’s slaves through new projects for The Jemima Code.

The first is a follow-up cookbook that Rizzoli will publish in 2016. The Joy of African American Cooking features 400 to 500 recipes tested for today’s home kitchen, tracing the history of dishes created by African American cooks over three centuries, including influences of Africa, the Caribbean, and the American South.

The John Egerton Prize I received from Southern Foodways Alliance inspired what came next. On Juneteenth weekend 2015 we held the first symposium dedicated exclusively to African American foodways in Austin, Texas. The event gathered scholars, researchers, students, journalists, authors, restaurateurs, farmers, chefs, activists, and anyone interested in exploring issues of social injustice through the lens of food for Soul Summit: A Conversation About Race, Identity, Power and Food.

The activities began on Emancipation Day (June 19) with a reception hosted by Leslie Moore’s Word of Mouth Catering with wines by Dotson-Cervantes and the McBride Sisters. We spent the next day and a half eating and drinking together on the grounds of Austin’s Historic Black College Huston-Tillotson University, while discussing the complex intersection of African American foodways traditions and how they have been used to define culture. Well-known and respected African American food industry experts including Jessica B. Harris, Twitty and the soul food scholar, Adrian Miller challenged our thinking about the foods that comprise the traditional African American diet, the ways those foods and the people who prepared them have been characterized and the impact of those representations on our communities. We explored the ways food continues to shape economic opportunities and community wellness and what some folks are doing about it. Renown African American chefs and mixologists, including Bryant Terry, Todd Richards, Kevin Mitchell, BJ Dennis and Tiffanie Barriere excited our palates with traditional, modern, and vegan fare. You can hear highlights, recorded in part, by a grant from Humanities Texas and Imperial Sugar, on SoundCloud.

Finally, I know that everyone can’t open the doors to a restaurant honoring the food and memory of a fabulous cook and relative the way that chef Chris Williams does every week with upscale, bowl-licking shrimp and grits at Lucille’s in Houston. So instead, I hope to reduce food shaming and “bring joy” to cultural eating through an online living cookbook and public archive that also picks up where The Jemima Code’s expanded history leaves off.

It is under construction now, but when business and sociology students are done with it this summer, the website will invite people of every culture to log-in, share recipes, photos, and stories about their favorite invisible cook. In my vision, this diverse group of “Jemimas” will turn the spotlight onto individuals so we can begin to embrace one another without prejudice or as members of a group associated with a particular race or food tradition.

If that’s not enough to spur joy in African American cooking, the comment section will remain open for other suggestions.

Discuss!

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 6, 2014 | Uncategorized

I am so excited.

After two years of writing, The Jemima Code – The Book is finally in production at the University of Texas Press. We are hoping for a fall 2015 release, with pop-up exhibits of photographs from the book planned as part of my book tour. In the meantime, I am working on a second book for The Jemima Code series and have re-dedicated this space to sharing my experiences as I cook with and learn from the African American cookbook authors of my rare collection and more.

My son and I are still tinkering with the layout for this journal, but my hope is that this space becomes a place where we exchange ideas about food and cooking — sharing tips, solutions, tools, gadgets, and resources — as we re-imagine the modern African American kitchen together.

Can’t hardly wait!

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jun 19, 2011 | Uncategorized

Today is Juneteenth, the day Texas slaves learned of their freedom. It is also the last day of the exhibit I co-curated at Project Row Houses in Houston as part of a fundraising effort I lead. The schedule of events is not a coincidence; it is one more example of the renewed spiritual presence of the women of the Jemima Code who are beginning to change lives one person at a time.

Last week, friend and colleague MM Pack visited 2515 Holman for a story she is writing for Gastronomica about the installation, Round 34: Matter of Food. We agreed not to talk about the project before she went, leaving the door open for her to have her own personal experience with the women and the space. Shortly after MM’s visit, I received this text: “I sure felt a strong spirit of your ladies in that house…”

Before MM, there was another text from journalist Bob Jensen. Bob is a radical writer, who turns scrutinizing observations into provocative articles that mix questions about women’s rights, public policy with admonitions for social accountability. He had been working on a piece about my advocacy and proudly reported the title he planned to pitch to internet publishers: “The Haunting of Toni Tipton-Martin.” He admitted that during our hours together, he had been “touched” too. (Bob shared his revelation shortly after we wrapped up installation of the screenprints of the women, when, as I wrote several blogs back, my image mysteriously appeared superimposed in the enlarged photograph of the exhibit’s main character, The Turbanned Mistress.)

Between texts, there were other spooky bursts including a report from a sharp graphic designer who noticed that my initials match the abbreviation we routinely use for The Turbanned Mistress — TTM.

All things considered, I suppose I am not surprised.

Twenty years ago, when I left a prestigious job at the Los Angeles Times to begin researching the women who cooked in America’s kitchens, my then editor and friend Ruth Reichl challenged me to stand unflinchingly on the work — however unpopular or controversial. Her advice made me feel like a rabble-rouser from the 1960s — the kind of person neo-soul crooner Jill Scott calls “the queen with the nappy hair raising a fist.”

In truth, steadfast activism was essential to liberty for American slaves and each of us practice it every time we resist the black cook stereotype with our embrace of uncomfortable feelings that tear down barriers.

The subject came up again last week when I introduced a Mid-Atlantic audience in Philadelphia to home economics instructors, like Carrie Alberta Lyford. As director of the Home Economics School at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, and a former specialist in Home Economics for the U.S. Bureau Of Education, Lyford instilled confidence and self-determination in her students in the early 20th century and she left behind several cookbooks and leaflets to prove it.

She inspired and influenced young women while advancing the University’s mission: “…to train selected Negro youth who should go out and teach and lead their people first by example…to teach respect for labor, to replace stupid drudgery with skilled hands, and in this way to build up an industrial system for the sake not only of self-support and intelligent labor, but also for the sake of character.” But, Lyford did more than just contribute to racial uplift.

When she created curriculum and textbooks for Hampton’s Home Economics students, she left a signature on the domestic science movement that was sweeping the nation at the time. Her work reveals exactly what she valued as important lessons for students, simple advice that emphasized freshness, seasonality and quality.

To my delight, Lyford worked hard as a health and nutrition activist, with complex health insights that told former slaves that steaming vegetables is preferred to boiling to retain nutritive value, that beans provide a good meat substitute, and that raw tomatoes are most attractively served washed and skinned, without scalding. She suggested economizing with attractive cream soups made from leftover vegetables. Devoted several sections to preparing, seasoning, and garnishing meats as well as the best way to make leftovers appetizing. She recommended adding onions and spices to parboiling water to improve flavor. And, her scientific directions for properly mixing batters and doughs were thorough and easy to understand.

You could say that Lyford epitomizes what happens when community-building, and fostering self-esteem are priorities provoked in individuals first.

I love that.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jun 16, 2010 | Uncategorized

I was busy digging around in American history looking for evidence that black cooks had earned the title of chef when the invitation to the White House arrived in my email. For years, I have been trying to clarify the fuzzy characteristics that epitomize chefdom in order to understand the role black cooks played in creating American cuisine. The First Lady turned that inquiry into a personal awakening.

You may remember from my last post that Michelle Obama called upon chefs from around the country to join her on the South Lawn as she introduced a new initiative in her Let’s Move campaign to help solve the childhood obesity epidemic in a generation. The invitation explained that the Chefs Move to Schools program would pair chefs with schools in their communities to teach kids about food, nutrition, and cooking in a fun and engaging way. And, it required those of us already working with schools to complete a questionnaire and chef’s profile.

The nonprofit organization I founded two years ago to teach cooking, heritage, and nutrition to underprivileged kids definitely qualified for the program, but me, a chef? I might be an excellent cook, but the difference between that and the artistry of a master chef is like comparing Derek Fisher to Kobe Bryant (I’m from Los Angeles; what do you expect?).

Eventually however, qualified sources convinced me that the women of The Jemima Code deserve chefdom. Maybe I do, too. The etymology of the noun chef is French, short for chef de cuisine, says Merriam-Webster. The term dates to 1840 and is defined simply as “a skilled cook who manages the kitchen.” In the 1977 edition of The New Larousse Gastronomique, the internationally-known culinary bible, the chef de cuisine is known as a “director responsible for a cooking team.” Chefdom, I reasoned, does not just mean one who is educated in classic technique at a well-equipped culinary academy — even though that is exactly the interpretation proclaimed by those with the synoptic view that “chefs are professionally trained, cooks are not.”

I filed the documents, packed my chefs whites, and got on the plane to Washington D.C.

The air was hot and sticky on the morning of June 4, filled as much with moisture as excitement, as I stood in line on East Executive Avenue NW waiting to clear the first secret service checkpoint. Friends and I gabbed nervously about work, pausing every now and then to marvel at the mist of nearly 700 chefs, and to take pride in the diversity of the crowd. Once through the second security stop, we received paper chefs hats with a Let’s Move message from First Lady Michelle Obama printed on the rim:

“We are going to need everyone’s time and talent to solve the childhood obesity epidemic and I am calling on our Nation’s chefs to get involved by adopting a school…you have tremendous power as leaders on this issue because of your deep knowledge of food and nutrition and your ability to deliver these messages in a fun and delicious way…”

Next it was off to the South Lawn. The mood was bright with exhilaration and we embraced one another while taking pictures as if we were little children on their first trip to a Disney theme park. Chefs posed everywhere: In front of the White House; beside the Ellipse; at the podium; between the collards and the rhubarb in the vegetable garden. After about an hour we wound our way through the gorgeous grounds, lured to the hilltop by the sound of a small band. We took turns alternating between saving seats and cooling off under the gallery of shade trees. Then an announcer asked us to be seated.

The anticipation was as high and our togues were drenched. In time, the chatter quieted to a hush and we sat on the edge of our seats watching and waiting for a sign of life at the door to the lower level of the White House. And then, she was there. Close enough to touch. Beautiful and poised. Articulate. Mrs. Obama echoed the remarks made earlier in the day at the Share Our Strength breakfast, encouraging the crowd, among other things, to be patient and considerate of cafeteria food service professionals — not just talented and skilled — when we set out to teach cooking and nutrition in schools.

The program concluded when the First Lady retreated to the garden to harvest vegetables with a few children and some of the food industry’s elite, including Marcus Samuelsson, Tom Colicchio, Cat Cora and Rachel Ray. The rest of the group remained in a glow of amazement, inspired by this executive expression of support, energized for the challenges that lay ahead.

And I contemplated a debt owed to generations of African American chefs who paved the way for me with little recognition — women who might have been asked to labor here, but never would have been treated to such an honor. I lingered a few minutes more in this opportunity of a lifetime, then peeled off my sweaty chefs coat — the one with The Jemima Code embroidered near my heart — and settled into my new role.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 14, 2010 | Uncategorized

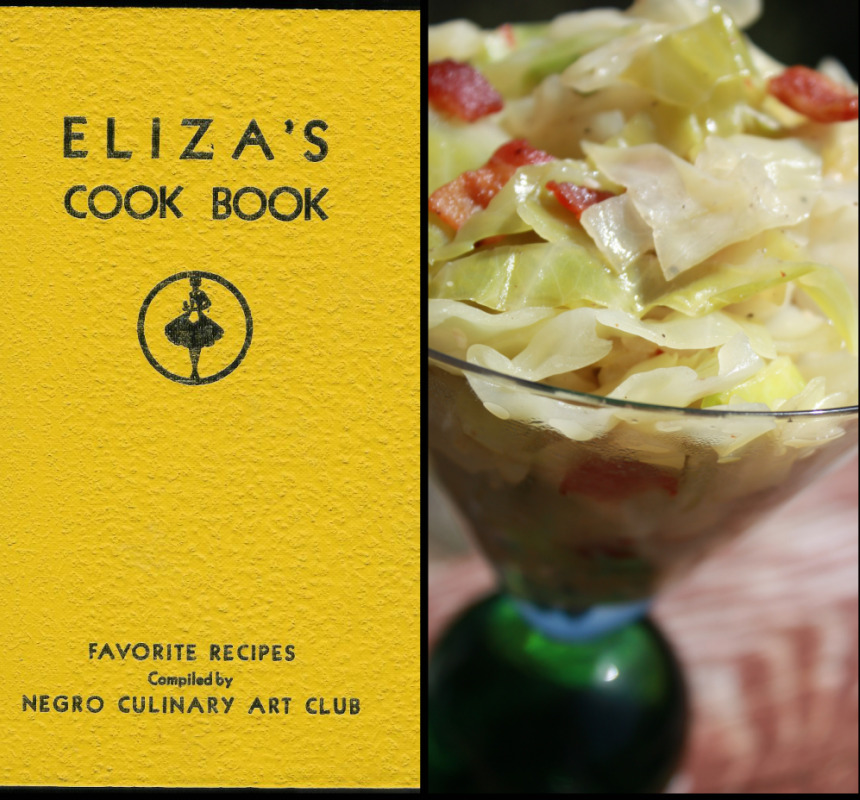

I had already imagined the delicacies and grace that would be rendered by Eliza’s Cook Book: Favorite Recipes Compiled by Negro Culinary Art Club of Los Angeles long before I ever bid my way to a rare and highly-coveted copy. I can tell you this sophisticated gem of some 100 pages is a miraculous find and a lovely example of African American flair in the ever-present asymmetry of the Jemima cliché. It shows that there was another side to black female cooks – a side with class.

Eliza was organized by Beatrice Hightower Cates and published at a time when national pursuits – from board games and radio to mystery novels by Agatha Christie – helped Americans escape the rigors of Depression-era living, while field writers for the Federal Writer’s Project, a part of the Works Progress Administration, recorded the life stories and oral histories of former slaves.

Amidst all the resources women had for scientific cooking and healthful meal planning the members of the Culinary Art Club obviously noticed a void. Cooking is indeed a science, but it is also an art – one that requires special attention, whether the cook is occupied with a simple method like brewing coffee or a more elaborate project, such as making a velvety sauce. Cates and the members of her club clearly knew the pleasures of fine cooking and took pride in their extensive catalog of “ladies’ luncheon” and light dinner dishes.

The recipes were decidedly upscale. To acknowledge the cultural tradition of hospitality and enrichment, Eliza was “Dedicated to the mothers of the members of the Culinary Art Club,” women who probably descended from slaves. And yet, I couldn’t help but notice once again how few historically Southern recipes are here. At first glance this practice seems disingenuous, but I don’t think it is as simple as that.

Eliza’s liberated cooks probably had unlimited access to finer cuts of meat and better quality vegetables, enabling them to extend their repertoire beyond biscuits, cornbreads, and croquettes. At least that’s what is reflected in the recipes they selected for their cookbook. Dishes range from assorted canapes, to creamy bisques and soups, saucy fish and lobster concoctions, all manner of meat and game (including steaks, roasts, and casseroles), vegetable sides from A to Z, and dozens of rich breads and sweets.

Neither cabin methodology nor the haze of hard labor that hovered over black kitchens appears to restrict their creativity. They didn’t let the yolk of tough economic times, lack of information, or even minimal cooking skills stifle them. Nor should we.

Times like these call for a return to the kitchen, and these women prove to us that trip doesn’t have to be laborious or difficult. Just get out a simple, but classic recipe and practice, practice, practice. When it’s time to serve your masterpiece, remember two the things the Culinary Art Club teach us: Exceptional cooks aren’t born, they are made; and attitude is everything.

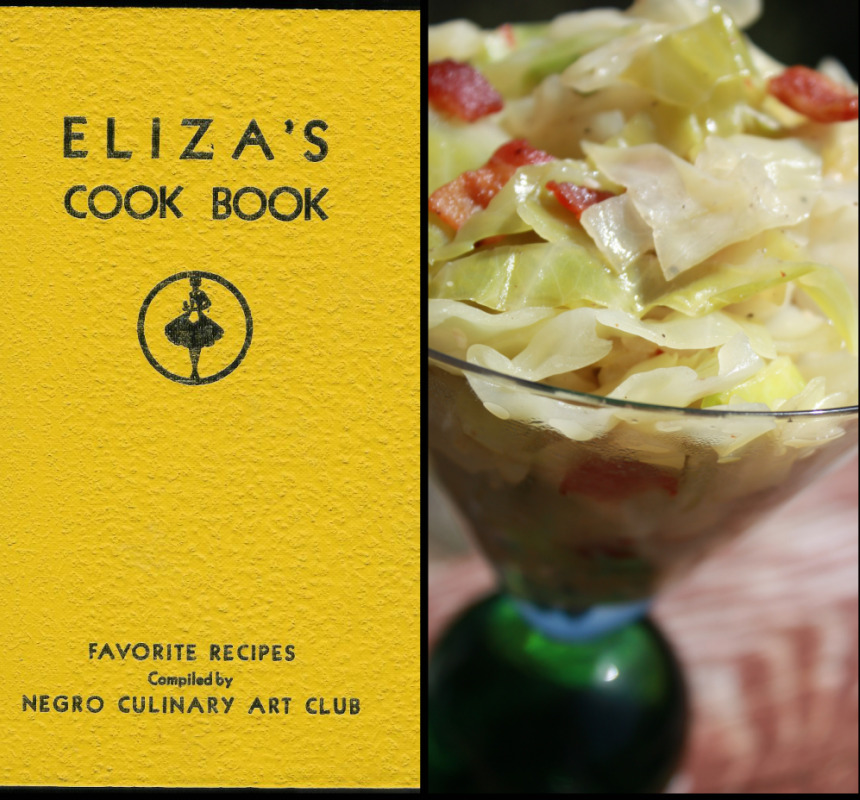

Even a homespun recipe like smothered cabbage can be made extra special, as Cates recommends. She simply layers shredded cabbage in a casserole with tomatoes, bacon, onions and green pepper, then crowns the dish with a dusting of Parmesan cheese before baking.

This basic cabbage saute should help get your imagination started.

In Her Kitchen

Sauteed Cabbage with Bacon

Ingredients

- 6 slices bacon, cut into pieces

- 1 medium onion, diced

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 small head cabbage, thinly-sliced

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon black pepper

Instructions

- Saute bacon in a hot skillet with a tight-fitting lid, until almost done. Add onion and cook until onion is translucent. Stir in garlic and cabbage and cook 3 to 5 minutes, stirring occasionally to prevent sticking. Cover skillet and reduce heat to low. Steam cabbage to desired doneness, 15 minutes for tender-crisp, 30 minutes for completely wilted. Season with salt and pepper before serving.

Number of servings: 6

In Her Kitchen

Comments