by Toni Tipton-Martin | Feb 7, 2014 | Caterers, Featured

Did you ever want something so bad it hurt? That’s how I feel about the last four First Edition African American cookbooks remaining on my Jemima Code shopping list. These extremely rare volumes are all that stands between me and a complete re-write of African American culinary history, told in the voices of the people who did the cooking.

But, this is the story of unrequited love.

My collection includes facsimile copies of these vintage works, and thanks to curators at the University of Michigan and Radcliffe University, I have held these precious gems in my hands, close to my heart. I can still remember how it felt to run my fingers over the gilded lettering engraved on the smooth surface of the cloth boards. I got cold chills as I opened the covers, exposed the fragile, yellowing pages, and uncovered hidden treasure.

Published in the years before and after the turn of the twentieth century, the recipe collections are the rarest of the rare. They are valuable to my mission because they reveal the true Knowledge, Skills and Abilities (KSA’s) possessed by black cooks, whether they were former slaves or free people of color.

It should make no difference that my copies are reproductions. But I want originals. The real thing. Badly. There is just something indescribable about owning such important pieces of history.

Last week, two of the books turned up in an online antiquarian bookseller’s catalog while I was driving to my office downtown. It had only been three hours since the announcement, but the most precious of the books — What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Southern Cooking — was already gone by the time I settled in and logged on. I recovered quickly from the shock of finding a volume published in 1881 by a former slave, Abby Fisher, for the low, low price of $4000.

I scrolled to the next entry on the list, The Southern Cookbook: A Manual of Cooking and List of Menus, published in 1912 by S. Thomas Bivins. My fingers went numb. Hurriedly, I moved the cursor over the price, and clicked. And prayed. The page advanced from the $95 price tag to Paypal and I screamed with delight:

“I got it!”

Featuring several hundred recipes, the Bivins book stands out among other African American works of the time as detailed as a textbook, but welcoming like a diary. This “manual of cooking and list of menus and recipes used by noted colored cooks and prominent caterers,” is a comprehensive study of the depth and breadth of the black cook’s repertoire, with formulas that validate the technical skills ordinary cooks possessed, but took for granted. Plus lots and lots of suprises.

From the author we learn: how to bone capon, to brew beer, to clean and dress fresh fish. We are regaled by innovative recipes such as rice pie crust, transparent marmalade, mushroom powder, and vegetable custard with splash of spinach juice. General rules of housekeeping, setting the table and curing the sick fill out his methodology.

I spent the next couple of hours going through my Zerox copy of Bivins’ book in a luxurious afterglow similar to the one Mariah Carey relished on her Butterfly album following an intimate encounter on the Fourth of July. In his Introduction, Bivins whispered his intentions and I swooned:

“In presenting this book to the public it is with the view of supplying the knowledge so much needed and sought for in a practical, condensed way, that shall give the home greater comfort; and the author hopes that after more than twenty years of experience and investigation he may be able to fill in a measure this long felt want.”

Then the unthinkable happened.

An email from Omnivore Books on Food explained that my request to purchase The Southern Cookbook collided with another buyer’s order. Bivins wasn’t really available after all.

So there I was, unfulfilled, left with only the hope that one day I might have my heart’s desire. I consoled myself with Bivins’ swaggering confidence:

“It is said that the mother who rocks the cradle controls the nation, but the domestic who faithfully and intelligently serves her who rocks the cradle is, in fact, the real ruler. Domestic service consists not simply in going the rounds and doing the humdrum duties of the house, but in scientifically cooking the food, in creating new dishes.”

I carry on.

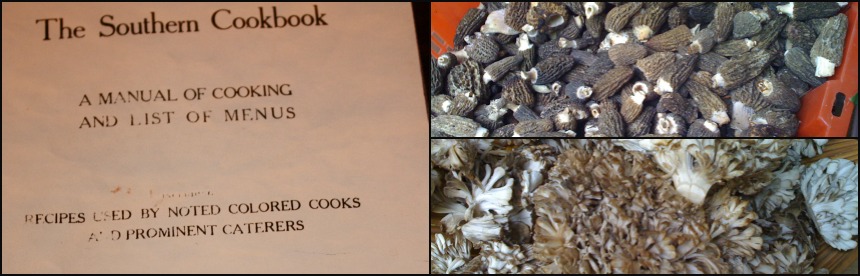

MUSHROOM POWDER

Wash half a peck of large mushrooms while quite fresh and free them from grit and dirt with flannel. Scrape out the back part clean, and do not use any that is worm-eaten; put them in a stewpan over the fire without water, with two large onions, some cloves, a quarter of an ounce of mace, and two spoonfuls of white pepper, all in powder. Simmer and shake them till all the liquor be dried up, but be careful they do not burn. Lay them on tins or sieves in a slow oven, till they are dry enough to beat to powder; then put the powder in small bottles, corked and tied closely, and keep in a dry place.

A teaspoonful will give a very fine flavor to any sauce; and it is to be added just before serving, and one boil give to it after it has been put in.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 10, 2010 | Entrepreneurs

I was hanging out in East Austin as Black History Month drew to a close when I happened upon a series of banners hanging around historic venues. The proud displays featured the names and pictures of local African Americans who had accomplished great things in various careers — from engineering and medicine to education and the arts. As you might have already guessed, women in the food industry were not included.

That is what makes antebellum African American cookbooks such an important and fascinating discovery for me. During Reconstruction, ex-slaves like Lucille Bishop Smith, Flossie Morris, and Mary Bernon were adding entrepreneurial skills to their culinary proficiency, but their work was unknown beyond the tiny communities in which they lived.

A former slave named Abby Fisher also established a reputation for excellence in cookery and business along the shores of the Pacific, but she did something extraordinary for the time: She published a cookbook to prove it. So did Malinda Russell, a free woman of color.

Although unschooled, Fisher operated a pickles and preserves manufacturing business with her husband, Alexander in San Francisco. She won awards and medals at various fairs in California. And in 1881 she released What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, a collection of more than 150 recipes – “a book of my knowledge, based on an experience of upwards of 35 years in the art of cooking.”

Fisher’s trailblazing cookbook bears witness to a legacy of excellence among black cooks, and to her hidden heritage of African-inspired dishes, including several for okra and black-eyed peas, gumbo, and jambalaya – noteworthy on any day, but exceptionally so during the prickly era of national reform in which she lived.

The Historical Notes in the Afterword to What Mrs. Fisher Knows, historian Karen Hess tells us why, in these tough economic times, we need to remember Abby Fisher: “She was clearly a remarkably resourceful woman, one of those strong matriarchal types who kept their families together under the most adverse circumstances.”

Malinda Russell’s A Domestic Cook Book: Containing Useful Receipts for the Kitchen, was a fragile, 40-page collection, printed in 1866 in Paw Paw, Michigan, before the Longone Center for American Culinary Research at the University of Michigan reproduced it. I was blessed to be part of the process, introducing Malinda to her first audience, and reminding them that this collection also teaches us how to use cooking to manage scarce resources.

In her brief autobiography, this free woman of color tells us a great deal about herself – a stark contrast to Fisher’s contrite spirit, and surprising considering the post-Civil War tensions of the time. She was a hard-working, single mother, a business owner, and the ladies of the community esteemed her.

Including their words of endorsement in her preface made good business sense, but we also can see the gesture as a measure of her integrity. Russell acknowledged everyone responsible for her talent and her project – an unusual action in light of the out-and-out plagiarism that was common practice among her publishing contemporaries. She said she apprenticed under the tutelage of Fanny Steward, a colored cook of Virginia, that she followed “the plan of The Virginia House-Wife,” and attribution accompanied several of her prescriptions.

Together, this free woman, Fisher, and to some extent the male authors of house servants’ guides, corroborate the notion of culinary literacy among black cooks. The modest collections of these masterful authors did for the art of African American cooking what Amelia Simmons’s little book did to distinguish the American cooking style from English cookery in 1796: They are like a culinary Emancipation Proclamation for black cooks.

*

Abby Fisher’s recipe for “Jumberlie — a Creole dish,” is a masterpiece of simplicity. It relies on farm-fresh chicken, smoked ham, and what she calls “high seasoning.” I’ve adapted her dish for modern kitchens, adding shrimp and sausage to the mix for a hearty one-pot meal. Serve it with crusty French bread and a cool crisp salad, and then wonder, as I do with every bite what delicacies the other women of the time might have left us if they had the means, time and resources to do so.

In Her Kitchen

Jambalaya

Ingredients

- 5 slices bacon, diced

- 1 onion, diced

- 1 green pepper, diced

- 1 stalk celery, diced

- 1 tablespoon minced garlic

- 3/4 teaspoon dried thyme

- 1 1/2 cups uncooked rice

- 1 cup diced tomatoes

- 3 cups chicken broth

- 1 bay leaf

- 1/2 pound smoked ham or sausage

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 teaspoon cayenne pepper

- 1/2 pound shrimp, peeled and deveined

- Hot pepper sauce

Instructions

- Fry bacon pieces in a deep skillet or Dutch oven until crisp. Remove to paper towels to drain and set aside. Add onion, green pepper, celery, garlic and thyme to the pan and saute until the vegetables are tender but still crisp. Add rice and continue to cook until the mixture is light brown. Stir in tomatoes, broth, bay leaf, ham, salt and pepper. Bring to boil, then reduce heat to simmer and cook, covered 15 minutes. Add shrimp to pan and cook 5 minutes longer or until shrimp turn pink. Adjust seasoning and serve with hot pepper sauce.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

Comments