by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 28, 2011 | Kitchen Tales

A warm, gentle breeze blew across the front porch at 2515 Holman causing the screenprint of the Turbanned Mistress to sway forward and back the way your grandmother might rock her chair to and fro after worship service on Sunday afternoon. It was as if she was there, watching and listening to our every word, waiting for the just-right moment to interject a remark. Which, of course, she never did.

Although her presence was felt as the inspiration for the intergenerational, gathering of women of varying cultures and backgrounds who came together on Easter weekend to share pie and kitchen memories at Hearth House, she did just what generations of black cooks always did: She simply faded into the background.

If you’ve been reading this blog, or have ever received my business card, then you know that the Turbanned Mistress is no longer living, but I keep her image alive through words, exhibits and whatever means necessary so that women like her who worked in America’s kitchens are not forgotten. She is one of five images of African-American cooks, who will be on exhibit at Project Row Houses in Houston’s historic Third Ward for PRH’s Round 34: Matter of Food from now through June 19, Emancipation Day.

I couldn’t help but notice the irony.

There we were. On Resurrection weekend. A group of strangers, getting acquainted through the simple and common act of sharing food and remembrance. Some of those present were passionate cooks. Others were just developing their culinary courage. At least one, admitted she was not a cook at all, but she did really love to eat. Whatever the motivation, we all had at least one thing in common — our hope that this, the first in a series of Apron Strings Community Conversations, would restore cooking to its rightful place as the center of family and home, while taking down barriers and building up community one person at a time. And, simultaneously, black cooks would be re-born.

Renatta is an artist and a self-proclaimed “preserver of tradition” determined to keep memories of gardening, crabbing and cooking with family alive. She took a seat at our long table of sisterhood alongside Tahila, Luanne, Razz, Linda, and three generations of women from Lily Grove Missionary Baptist Church, who not only came to join the conversation, but agreed to be part of our oral history project with the University of Houston and Foodways Texas, which will collect stories and recipes of Texas women.

Crystal Granger, the center of the generations and an architect, described how she learned to appreciate the precision and science of cooking from her grandmother who practiced a particular kind of mise en place. The artsy side of her culinary skill, she explained, comes from her mother, Shirley. Shirley, a former teacher, now spends her days motivating seniors toward active living, employing some of the same strategies that once helped her inspire youngsters to learn. As she regaled us with her special way of coaxing reluctant seniors out of the withdrawl that can come with aging, her mastery of culinary art as an educational tool that can nurture became evident. With Crystal, Shirley, and Aunt Marva Smith as role models, it’s no wonder grand-daughter Chimere has such incredible passion for baking and a joy for living.

This coming weekend, the Granger family will be interviewed by students from the University of Houston’s Department of History. They will talk about their tea cake chronicles and the important life-skills they developed while cooking and baking together. The goal of the project is to break the Jemima Code by creating a permanent record that documents and preserves African-American culinary truth for future generations of individuals and researchers, too.

Paradoxically, if someone had bothered to interview the Turbanned Mistress and capture her testimony she would certainly have communicated a few simple anecdotes about life during slavery, but like parables, her experiential yarns would likely have revealed her secrets of emotional and physical survival under barbaric circumstances, too. And that translates into useful lessons about perseverance and discipline, tolerance and self-worth.

Linda Shearer, director of PRH put the whole process in perspective — comparing our Easter gift with the narrative artistry of John Biggers and the way he used cultural heritage and everyday experiences to change the perception of African Americans.

“Your life can be your art,” Shearer said, as the afternoon drew to a close and we all basked in the glow of new relationships defined by a shared intimacy. “We all have a creative side, but it can take a wide variety of shapes and form. What goes on here is you learn from each other.”

* * *

If you would like to join our conversation and give new life to the subject of African-American foodways, the next Apron Strings kitchen table conversation will take place at Hearth House, at Project Row Houses (projectrowhouses.org) in Houston on May 21.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 12, 2011 | Plantation Cooks

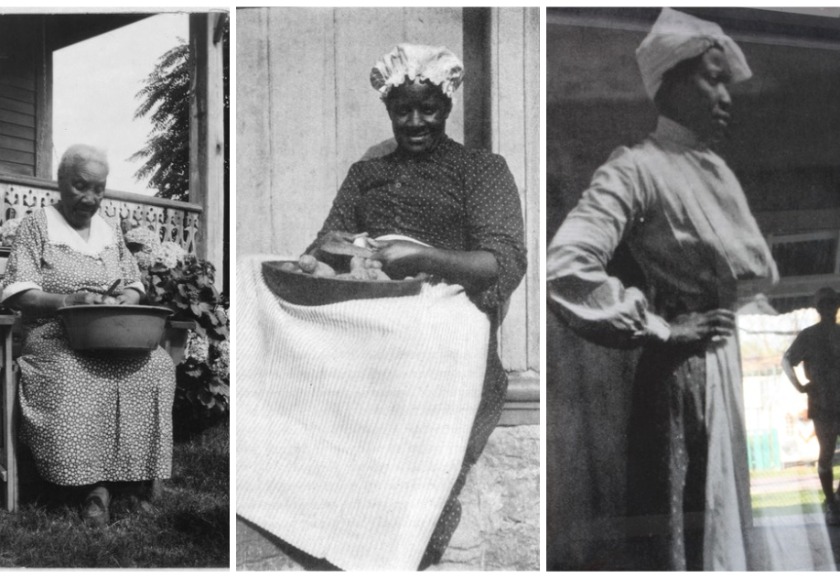

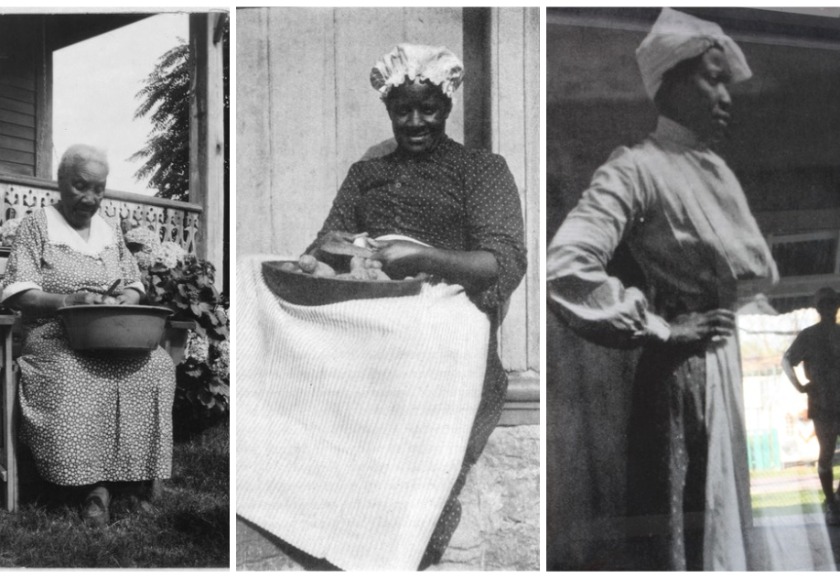

Betty Simmons sits leisurely on the back porch at 2515 Holman, in Houston’s historic Third Ward with a big, round metal pot in her lap and a curtain of voluptuous hydrangeas as her backdrop. She has a small knife in one hand, peeling what appears to be potatoes. Her white hair is brushed back away from her face, revealing a surprisingly supple and healthy look for a woman of nearly 100. The chain link of a porch swing is barely visible beyond the ornate railing.

Betty is one of five Jemima Code women who are on exhibition through June 19, at Project Row Houses, Round 34 Matter of Food. My artist friend and Peace Through Pie partner Luanne Stovall and I are co-curators of Hearth House, a traveling installation where Betty and the cooks of the Blue Grass Cook Book (the Turbaned Mistress, Aunt Frances, Aunt Maria and Aunt Dinah) are capturing the hearts of visitors just about as much as they enchant us.

Some years ago, as I fretted on a Southern Foodways Alliance excursion over the loss of these women, my friend and mentor John Egerton asked me whether they were haunting me. I shared his silly question with some artsy friends who were having their own unique, spiritual responses to the women. Before we knew it, the idea for the Project Row Houses exhibit materialized.

That phenomenal creative team (Ellen Hunt, Meeta Morrison, Luanne and I) digitized and enlarged the women’s images onto seven-foot-tall, transparent screen-like fabric that is suspended from the ceiling in one of seven shotgun-style houses at PRH.

Of course, we all knew that in order to break the code, the space had to be beautiful, so the walls were painted in warm colors that bring thoughts of sweet potatoes, sorghum and sunflowers to mind. The text is minimal — drawn from the inspirational words of Mary McLeod Bethune and from the women themselves. And, a fourth wall, painted in chalkboard paint, provides a space for the community to share kitchen memories and pie stories (which we erase periodically to symbolize the way the women were erased from history). A rough-hewn long table invites guests to linger and to leave their kitchen tales on recipe cards that will become part of our permanent archive.

When the banners were first unrolled, I actually lost my footing and crumbled onto the floor. And cried. I’d spent so many years waiting for these women to finally be honored. To top it off, on our final day of installation, my mother noticed that as I stood on the back porch of the house just beyond the screen of my favorite, the Turbaned Mistress, my silhouette was eerily superimposed into the screen like the shadow of a child, ready for tutelage at her side. Thank goodness she had the sense to photograph the moment. Obviously, the mystery of the women is very personal. And, it is palpable.

Since Opening Day, people visiting the exhibit have written to confess their experiences, too. They tell me how Aunt Frances looks over them in different ways depending upon the sunlight, or when the hot, humid breeze blows through the house at different times of day.

Is there something special to know about Betty?

Betty was one of those extraordinary slave girls, who grew up in the kitchen in the shadow of a phenomenal Texas cook who had absolutely no idea she was saving a child’s life as she passed on culinary skills casually, one meal at a time. But, she did.

Betty was born a slave to Leftwidge Carter in Macedonia, Alabama, then she was stolen as a child and sold to slave traders, who later sold her in slavery here in Texas, where her cooking skills protected her from a harsh life of field labor in slave times, and helped her manage scarce resources in freedom.

She was interviewed at a time when national pursuits – from board games and radio to mystery novels by Agatha Christie – helped Americans escape the rigors of Depression-era living, and field writers for the Federal Writer’s Project recorded the life stories and oral histories of former slaves.

Sadly, the government didn’t think to ask many questions about food and cooking, but I’m not mad at them. Fortunately for all of us, the conversational style of Betty’s narrative gives an intricately detailed look at the precarious life of a slave cook working at a Texas boarding house. I learned a little about humility, charity and self-respect from Betty. And, after months of putting the wrong things first in my life, I’m hoping she will help me get my priorities straight from today forward.

What do her words encourage you to do?

Here is a bit of her story:

When massa Langford was ruint and dey goin’ take de store ‘way from him, day was trouble, plenty of dat. One day massa send me down to brudder’s place. I was dere two days and den de missy tell me to go to the fence. Dere was two white men in a buggy and one of ‘em say I thought she was bigger dan dat,’ Den he asks me, ‘Betty, kin you cook? I tells him I been the cook helper two, three month, [Betty’s aunt Adeline was the Langford’s cook] and he say, ‘You git dressed and come on down three mile to de other side de post office.’ So I gits my little bundle and when I gits dere he say, “gal, you want to go ‘bout 26 mile and help cook at de boardin’ house?

Betty’s narrative ends with a sad revelation that her massa eventually did lose everything he owned to creditors — including his slaves. She and the remaining servants were sent to various traders — some benevolent, some harsh — in Memphis and New Orleans. Eventually, Betty the child winds up in Liberty, Texas, where she conveys a message that still resonates for for everyone trying to make it through difficult times — including me:

We work de plot of ground for ourselves and maybe have a pig or a cuple chickens ourselves…We gits on alright after freedom, but it hard at furst ‘cause us didn’t know how to do for ourselves. But we has to larn.

Comments