BETTY SIMMONS: IT WAS HARD BUT WE HAD TO LEARN

Betty Simmons sits leisurely on the back porch at 2515 Holman, in Houston’s historic Third Ward with a big, round metal pot in her lap and a curtain of voluptuous hydrangeas as her backdrop. She has a small knife in one hand, peeling what appears to be potatoes. Her white hair is brushed back away from her face, revealing a surprisingly supple and healthy look for a woman of nearly 100. The chain link of a porch swing is barely visible beyond the ornate railing.

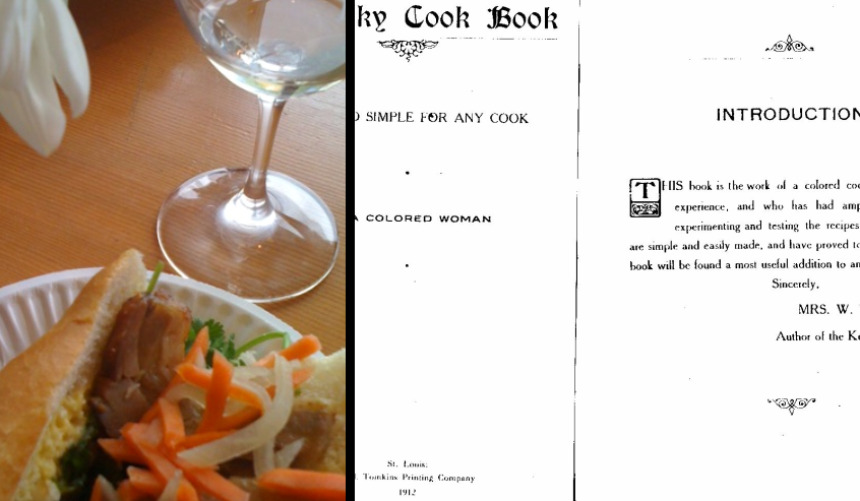

Betty is one of five Jemima Code women who are on exhibition through June 19, at Project Row Houses, Round 34 Matter of Food. My artist friend and Peace Through Pie partner Luanne Stovall and I are co-curators of Hearth House, a traveling installation where Betty and the cooks of the Blue Grass Cook Book (the Turbaned Mistress, Aunt Frances, Aunt Maria and Aunt Dinah) are capturing the hearts of visitors just about as much as they enchant us.

Some years ago, as I fretted on a Southern Foodways Alliance excursion over the loss of these women, my friend and mentor John Egerton asked me whether they were haunting me. I shared his silly question with some artsy friends who were having their own unique, spiritual responses to the women. Before we knew it, the idea for the Project Row Houses exhibit materialized.

That phenomenal creative team (Ellen Hunt, Meeta Morrison, Luanne and I) digitized and enlarged the women’s images onto seven-foot-tall, transparent screen-like fabric that is suspended from the ceiling in one of seven shotgun-style houses at PRH.

Of course, we all knew that in order to break the code, the space had to be beautiful, so the walls were painted in warm colors that bring thoughts of sweet potatoes, sorghum and sunflowers to mind. The text is minimal — drawn from the inspirational words of Mary McLeod Bethune and from the women themselves. And, a fourth wall, painted in chalkboard paint, provides a space for the community to share kitchen memories and pie stories (which we erase periodically to symbolize the way the women were erased from history). A rough-hewn long table invites guests to linger and to leave their kitchen tales on recipe cards that will become part of our permanent archive.

When the banners were first unrolled, I actually lost my footing and crumbled onto the floor. And cried. I’d spent so many years waiting for these women to finally be honored. To top it off, on our final day of installation, my mother noticed that as I stood on the back porch of the house just beyond the screen of my favorite, the Turbaned Mistress, my silhouette was eerily superimposed into the screen like the shadow of a child, ready for tutelage at her side. Thank goodness she had the sense to photograph the moment. Obviously, the mystery of the women is very personal. And, it is palpable.

Since Opening Day, people visiting the exhibit have written to confess their experiences, too. They tell me how Aunt Frances looks over them in different ways depending upon the sunlight, or when the hot, humid breeze blows through the house at different times of day.

Is there something special to know about Betty?

Betty was one of those extraordinary slave girls, who grew up in the kitchen in the shadow of a phenomenal Texas cook who had absolutely no idea she was saving a child’s life as she passed on culinary skills casually, one meal at a time. But, she did.

Betty was born a slave to Leftwidge Carter in Macedonia, Alabama, then she was stolen as a child and sold to slave traders, who later sold her in slavery here in Texas, where her cooking skills protected her from a harsh life of field labor in slave times, and helped her manage scarce resources in freedom.

She was interviewed at a time when national pursuits – from board games and radio to mystery novels by Agatha Christie – helped Americans escape the rigors of Depression-era living, and field writers for the Federal Writer’s Project recorded the life stories and oral histories of former slaves.

Sadly, the government didn’t think to ask many questions about food and cooking, but I’m not mad at them. Fortunately for all of us, the conversational style of Betty’s narrative gives an intricately detailed look at the precarious life of a slave cook working at a Texas boarding house. I learned a little about humility, charity and self-respect from Betty. And, after months of putting the wrong things first in my life, I’m hoping she will help me get my priorities straight from today forward.

What do her words encourage you to do?

Here is a bit of her story:

When massa Langford was ruint and dey goin’ take de store ‘way from him, day was trouble, plenty of dat. One day massa send me down to brudder’s place. I was dere two days and den de missy tell me to go to the fence. Dere was two white men in a buggy and one of ‘em say I thought she was bigger dan dat,’ Den he asks me, ‘Betty, kin you cook? I tells him I been the cook helper two, three month, [Betty’s aunt Adeline was the Langford’s cook] and he say, ‘You git dressed and come on down three mile to de other side de post office.’ So I gits my little bundle and when I gits dere he say, “gal, you want to go ‘bout 26 mile and help cook at de boardin’ house?

Betty’s narrative ends with a sad revelation that her massa eventually did lose everything he owned to creditors — including his slaves. She and the remaining servants were sent to various traders — some benevolent, some harsh — in Memphis and New Orleans. Eventually, Betty the child winds up in Liberty, Texas, where she conveys a message that still resonates for for everyone trying to make it through difficult times — including me:

We work de plot of ground for ourselves and maybe have a pig or a cuple chickens ourselves…We gits on alright after freedom, but it hard at furst ‘cause us didn’t know how to do for ourselves. But we has to larn.

Comments