by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 8, 2014 | Entrepreneurs, Featured, Soul Food Cooks, The Modern Kitchen

“Rise up, ye women that are at ease! Hear my voice ye careless daughters! Give ear to my speech.”

— Isaiah 23:9

You may have been surprised to see so few posts about women last month on a blog that is named after a woman.

From memorable historic figures, to my friends Michael Twitty and Adrian Miller, February was a time to celebrate the achievements of male African American food industry professionals — written history makes it so much easier to report the culinary accomplishments of men. W. E. B. Dubois, for example, praised male caterers in his sociological study, The Philadelphia Negro, while the personal papers of Presidents Washington and Jefferson elevated male kitchen workers from slave to chef status — ignoring Edith Fossett’s legacy of French cuisine, once characterized by Daniel Webster as “good and in abundance.”

It is time to get back to The Ladies.

To celebrate Women’s History Month, the Jemima Code exhibit hits the road tomorrow, sharing life-changing culinary truths, and rewriting black women’s history, one recipe and one audience at a time.

Our first stop is part of a series of events hosted by the University of North Carolina – Charlotte’s Center for the Study of the New South, which will explore the history of race in southern kitchens and includes a two-day conference in September entitled: “Soul Food: A Contemporary and Historical Exploration of New South Food.” Then we are off to Chicago for the 36th annual conference of the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP).

“The Jemima Code fits into the Center’s study of new south food by bringing life to the untold history, triumphs and struggles of one of the primary groups, African American women, associated with what we call southern food,” said Jeffrey Leak, director of the Center and Associate Professor of English. In presenting the Jemima Code in multiple settings — campus, church, and museum — the University hopes to demonstrate its commitment to community engagement and to sharing knowledge with other institutions in the community, Leak explained. “In doing so, we create the possibility of improving upon or creating relationships with these institutions that will lead to collaborative approaches to some of our communities most difficult challenges.”

Jemima Code events kick off with a talk and tea hosted by UNCC and the Social Justice Ministry at Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, featuring the memories of a former slave from Asheville, Fannie Moore. In her WPA interview, Moore details the family technique for preserving peaches showing us how slaves practiced local, seasonal, organic and sustainable living and underscoring the message: “claim your heritage to reclaim your health.”

Next, we’re off to a meeting with students in UNCC’s College of Liberal Arts & Sciences focused on a few ways recipes and cookbooks preserve identity. We will uncover evidence of entrepreneurial and personal values like industriousness and discipline in Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which the former slave observed in her grandmother, a cookie vendor.

On Monday, at an intimate reception, conversation and Jemima Code exhibit at the Levine Museum of the South, guests will be surprised and amazed by African American kitchen proficiencies in stories told by author and R & B singer Sheila Ferguson.

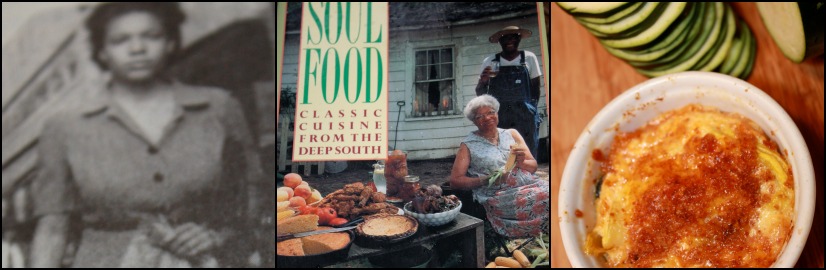

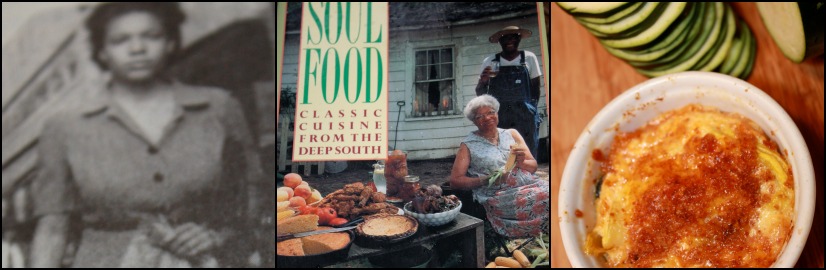

In her 1989 cookbook, Soul Food Classic Cuisine from the Deep South, the former lead singer for the Three Degrees writes in a fast-talking, jive-style that is complete with snappy expressions and memories of cooking and eating at home with family and friends. She has a theory that cooking the soul food way means “you must use all of your senses. You cook by instinct, but you also use smell, taste, touch, sight, and particularly, sound…these skills are hard to teach quickly. They must be felt, loving, and come straight from the heart and soul.” To prove it, she esteems family members, including her Aunt Ella from Charlotte, writing about brilliant dishes of animal guts smothered with rich cream gravy in a colorful rhythm that might just make you want to run out and trap a possum. For real.

Finally, a conversation at IACP on March 16 will explore lessons in culinary justice taught by iconic Chicagoland cookbook authors, like Freda DeKnight. Food writer Donna Pierce helps me set the table with her research on the culinary industry’s middle class. We wrap up with an interactive workshop that I hope will spur Jemima Code audiences to enact what they discover about black cooks, with inspiration from these adapted words of abolitionist Lydia Maria Child:

“For the sake of my culinary sisters still in bondage…”

In Her Kitchen

Aunt Ella’s Squash Bake with Cheese

Ingredients

- 5 cups sliced thin-skinned yellow squash

- 3 tablespoons butter or margarine

- 1/4 cup chopped green pepper

- 1/4 cup chopped onion

- 1/4 cup chopped celery

- 1 (10.5-ounce) can cream of mushroom soup

- 1 egg, slightly beaten

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 teaspoon black pepper

- 1/2 cup grated Cheddar cheese

- 1/4 cup fresh breadcrumbs

- Paprika, optional

Instructions

Cook the squash in 1/4 to 1/2 cup water for 10 to 15 minutes or until fork tender. Drain well and puree it. Melt 2 tablespoons butter in a skillet over medium yeat and sauté your onion, celery, and green pepper until soft, about 5 minutes. Add the soup, undiluted, and cook, stirring constantly, until the soup is smooth and well-blended with the vegetables.

*Serves 6-8

Preheat your oven to 375 degrees.

In a medium-sized bowl, mix but do not beat your squash puree, soup and vegetable mixture, with the egg, salt, pepper, and half of the cheese. Pour into a well-greased 1 1/2 quart baking dish. Mix the remaining butter with the breadcrumbs and the rest of the cheese, and spread this over the top of the squash. Sprinkle with paprika if desired. Bake in the oven for 35 to 45 minutes or until your squash bake is brown and bubbly.

Variation: Do not puree squash. Substitute evaporated skim milk, 2 eggs and 1-2 tablespoons melted butter for the canned soup and 1 egg.

Aunt Ella is one of the finest soul food cooks in our family and she makes squash taste like something out of this world. If you can’t find the right kind of squash this is almost as good made with courgettes.

Adapted from Soul Food: Classic Cuisine from the Deep South, by Sheila Ferguson

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 30, 2014 | Entrepreneurs

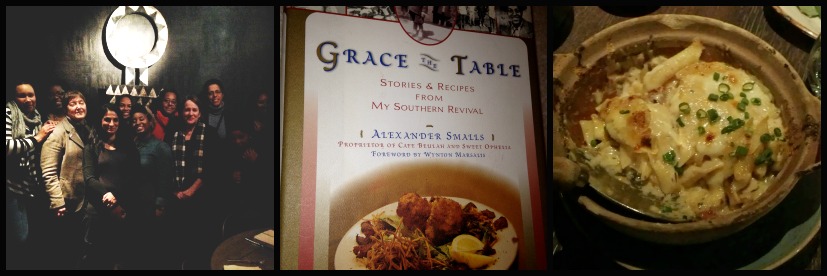

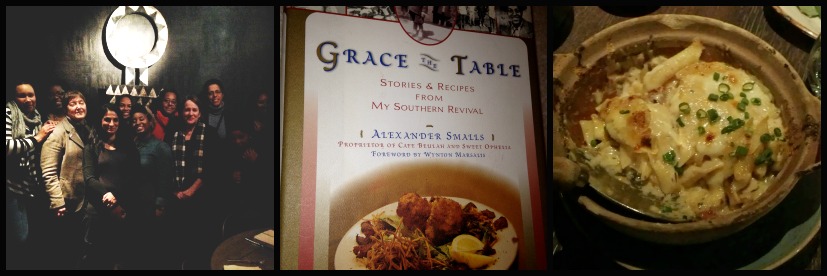

Last week on a frigid Thursday evening, I found myself in Harlem surrounded by snow drifts, a dozen Facebook food friends, and inspired Afro-Asian cuisine at Alexander Small’s sexy new restaurant, The Cecil. An ensemble of attentive waiters played their parts with aplomb in the dimly-lit dining room, recommending southern-styled cocktails and dishes that layer classic and global flavors, as we pondered what has changed for blacks in the food industry, what hasn’t and what we can do about it.

I was in New York for a meeting of the James Beard Broadcast Media Awards committee, noticeably agitated by the dearth of African American entries, and fresh off a panel in Austin on the subject of new media, women and food. My thoughts were still swirling around issues of access, increased opportunities, and competition created by the Internet, but I was absolutely delighted by this chance for kinship with talented, up and coming food industry folks who share my fascination with the African American food legacy, and the authors of The Jemima Code.

One of those enthusiasts, culinary historian Michael Twitty, was unable to join us, but he and I will continue the conversation this Saturday when we co-present History Around the Table: African American Cooks and Our Culinary History at the French Legation Museum in Austin. Twitty soared to the forefront of the foodie conscience after writing an impassioned letter to beleaguered Paula Deen and appearing on the PBS special, African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Having spent more than 30 years learning, thinking and writing about food in traditional media, I have been thrilled to celebrate its accolades for Twitty, and now for The Cecil’s Chef de Cuisine Joseph “JJ” Johnson and its opera singer-owner Alexander Smalls. That night, not even the disappointing showing among the award nominees could overshadow the essence of my optimism for the future: professional excellence, coalition building and “fusion cuisine.”

Fusion cooking is the same cultural blending practiced by our ancestors who melded European and African techniques with the indigenous ingredients of the Americas into a hallowed (southern) cuisine. Scholars have used various titles to summarize it — “African grammar,” “wok presence,” “Creolization” — but it took 1990s chefs to apply arts and music terminology to the rich exchange, and to make it stick.

Back then for example, accomplished restaurant and catering chef Jeanette Holley wore her African American fusion sensibilities like a culinary badge of honor. Born to a Japanese mother and a black father, she built her reputation on the best of what each culture had to offer. Ginger and rum spiced sweet potato pie. Asian flavors, such as star anise, coriander, and Szechwan peppercorns dusted barbecued pork spareribs. It was a glorified style that “borrowed parts from each other to develop a new language of their own,” she said in a news article for the Los Angeles Times Syndicate.

Long before there was The Cecil, the fusion way also made it possible for Smalls to blend his penchant for storytelling and his love of southern food with international flair into acclaimed restaurants and a 1997 cookbook, Grace the Table: Stories & Recipes From My Southern Revival, where Sweet Potato Waffles and Peach Cobbler hold their own alongside Sea Bass Wrapped in Lettuce Leaves and Pork Masala with Mixed Greens.

As trailblazers, all three gentlemen are obviously imaginative and talented and able to show the world what happens when we look back at historic foods and classic cooking methods with reverence, but employ them as stylish flourishes rather than remnants of poverty and survivalist cooking. And, they are living, breathing evidence of the old saying: “Attitude is everything,” whether we are talking about Twitty’s blending of Jewish and African American culinary histories, or Johnson’s Afro/Asian/American Oxtail Dumplings, Collard Green Salad, and Macaroni Cheese Casserole (accented with rosemary, caramelized shallots, and pepper ham), This is certainly good news and a sign of changing times for other aspiring men in food.

So what about women like Holley? Isn’t it time for strong young ladies to enjoy the accolades and benefits associated with artistic blending in the kitchen?

You may already know about the firestorm created by a recent Time Magazine cover story that ignored female chefs in general, but for me it renewed dialogue about the barriers to entry for black women chefs, too.

Disregarding the accomplishments of black women is not new. From the very beginning, traditional media has paid more attention to black men, publishing their recipe books in the trade, maintaining records of their careers in catering, building cooking shows around them, and crowning them with title of “chef” whether they cooked on the Pullman Railroad, on college campuses, in hotel dining rooms, or in the White House.

With new media, however, culinary honor may finally be possible for young female food professionals of color — like my dinner companions — who are standing out, and up for themselves, while promoting and supporting one another. (With encouragement from established industry veterans; thanks Nancie, June, Debbie, Michelle, Ramin and Scott.)

Therese Nelson is a graduate of Johnson and Wales who founded the website Black Culinary History to document industry diversity and provide a space for networking; Elle Simone is a freelance chef and Food Network food stylist who studied at the Culinary Academy of New York and created SheChef, a mentoring program that fosters self-confidence and excellence in culinarily-focused young women from urban settings; Nicole Taylor, a self-described “artisan candy maker, activist, social media maven,” hosts Hot Grease, a progressive food culture radio program on Heritage Radio Network; Sanura Weathers blogs about her food studies and passion for cooking at home; multi-talented, singing chef Jackie Gordon set a tasting of New York artisan chocolate makers to music in her newest show, Chocabaret; chef Nadine Nelson, a culinary educator, community activist and event planner, celebrates world cuisines on two sites, Global Local Gourmet and Epicurean Salon; and Sarah Khan, a journalist at zesterdaily.com hopes to inspire social change around local, national, regional, and global foodways as director of the Tasting Cultures Foundation.

As our evening at The Cecil drew to a raucous close, several of these active “next generation” women leaned in with deep emotion and described her own sense of ambition and dedication sparked by Jemima Code authors — women (mostly) and some men — who lived, worked, and achieved success in the media’s culinary shadows.

My heart filled with hope that someday soon more women of color will be counted among culinary royalty and perhaps win awards for what we accomplish in new and traditional media — or bricks and mortar.

In His Kitchen

Shrimp Paste with Hot Pepper

Ingredients

- 1/2 pound large shrimp, peeled, deveined, and poached

- 1/2 cup black-eyed peas, cooked

- 1/2 cup chickpeas, cooked

- 3 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 jalapeño pepper, minced

- 1/2 teaspoon cayenne pepper

- Juice of 4 lemons

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 cup mayonnaise

- 1/4 cup cilantro, chopped

- 3/4 cup olive oil

Instructions

Place all ingredients except olive oil in a large bowl of a food processor. Pulse until smooth. With machine running, pour in olive oil and pulse until thickened. Check seasoning. Serve in a medium-sized bowl, accompanied by a breadbasket.

Makes 8 Servings

From Grace the Table: Stories & Recipes From My Southern Revival, by Alexander Smalls

In His Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 11, 2012 | Entrepreneurs, Featured

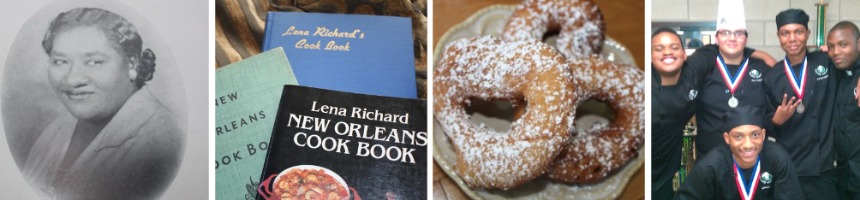

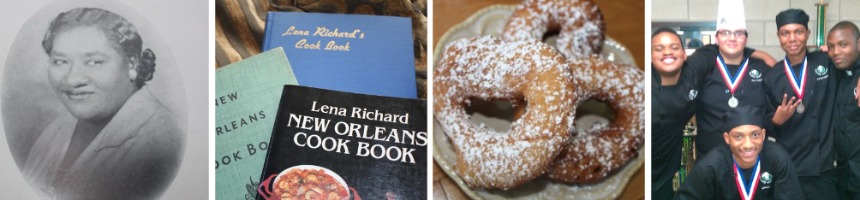

I went to the safe to retrieve a New York-area author from the Jemima Code cookbook collection to be among the black cooks featured in my pop-up art exhibit at the Greenhouse Gallery at James Beard House in Manhattan. I came out with New Orleans chef Lena Richard. More than 70 years ago, the “father of American cuisine” had been Richard’s advocate. Now, she would return to his home to uplift and encourage a whole new generation.

Until recently I had only briefly studied Richard’s life. I read in a resume of her accomplishments in the exhibition guide at Newcomb College Center for Research on Women at Tulane University, that she was a formally trained culinary student, completing her education at the Fannie Farmer Cooking School in Boston. She ran her own catering company for ten years, operated several restaurants in New Orleans, including a lunch house for laundry workers, cooked at an elite white women’s organization, the Orleans Club, opened a cooking school, and taught night classes while compiling her cookbook.

In 1939, she self-published more than 350 recipes for simple as well as elegant dishes in Lena Richard’s Cook Book. Her smiling face radiates from the kind of ladylike portrait one might expect to find cradled inside a gold locket worn close to the heart. A year later, at the urging of Beard and food editor Clementine Paddleford, Houghton Mifflin published a revised edition of her work. This book, however, contained a new title and preface, and that precious cameo-style photograph was gone.

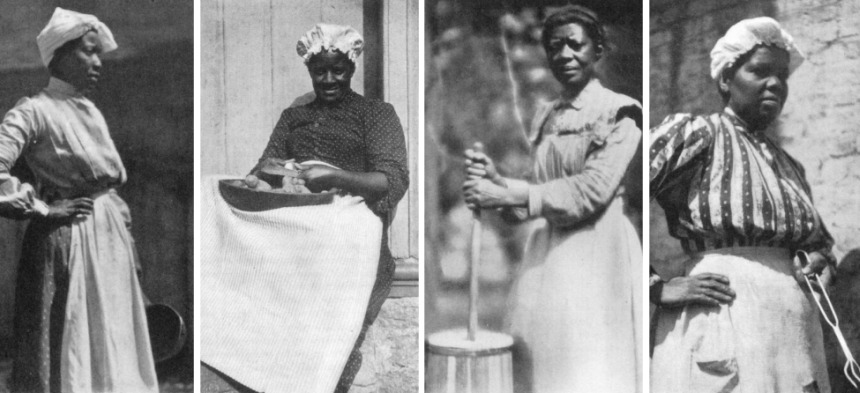

Through the end of April, visitors to Beard House were welcomed into the sanctuaries of unsung culinary heroes like Richard. Screen-printed images of black women at work in and around the kitchen hearth in slave and sharecropper’s cabins, gardens, and in shotgun houses throughout the south hung on the walls of the Greenhouse. The images in this engaging visual history were taken from my historic reprint of a 1904 classic cookbook, The Blue Grass Cook Book — photographs that document culinary contributions to American cuisine and establish an enduring legacy for the women as modern role models who encourage everyone to cook and share real food.

In these times of Top Chef-styled plates where food is stacked, foamed and streaked, it can seem impossible to be impressed by the simplicity of three-course menus comprised of dishes like avocado cocktail, buttered saltines, broiled steak, petit pois, and watermelon ice cream — but we should try.

So, in celebration of the hard-working, nimble chef who taught culinary students how to make homemade vol-au-vent and calas toud chaud while tutoring her daughter in the entrepreneurial skills of business 101, and as part of my outreach to vulnerable children in Austin, and in partnership with the James Beard Foundation, the University of Texas, the Texas Restaurant Association, and Kikkoman, four high school culinary students cooked for a reception featuring chef Scott Barton, April 1 at the Beard House.

For the past three years, students from Pflugerville’s John B. Connally High and Austin’s Travis High have demonstrated professionalism, self-awareness, and pride in the presence of these art works, the kind of outcomes we can expect when we provide culturally-appropriate experiences that engage and inspire kids toward careers in the food industry — whether those jobs are in food archaeology, anthropology, food service, or public health.

Ryan Johnson, a senior at Connally described the meaning of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity this way: “Most people my age have never heard of the James Beard Foundation, or the IACP, but as soon as Chef mentioned those names, I couldn’t believe my ears. I thought. “No way!

“Every night this week, I could hardly sleep because of the anticipation, and thoughts of the different people I’ll meet, and foods I’ll see. My mom always wanted me to be as passionate about food as she is; her wish has come true. I am truly grateful for the wonderful opportunities my passion and hard work have brought me, and I can’t help but think, “I’m actually going to be a chef…”

For information about The Jemima Code exhibit at the James Beard House Greenhouse Gallery, visit:

http://www.jamesbeard.org/index.php?q=greenhouse_gallery

In Her Kitchen

Lena’s Doughnuts

Ingredients

- 2 cups sifted flour

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon each ground nutmeg and cinnamon

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1 egg, well beaten

- 1 tablespoon melted butter

- 1/2 cup milk

Instructions

Sift flour once, measure, add baking powder, salt, nutmeg and cinnamon. Sift together, three times. Combine sugar and egg; add butter. Add flour, alternately with milk, a small amount at a time. Beat after each addition until smooth. Knead lightly 2 minutes on lightly-floured board. Roll 1/3-inch thick. Cut with doughnut cutter. Let rise for several minutes. Fry in deep, hot fat until golden brown. Drain on unglazed paper. Sprinkle with powdered sugar, if desired.

Number of Servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 6, 2011 | Entrepreneurs

It seems hard to believe that nine months have whizzed by without even a peep from me and the women of the Jemima code. Please forgive us; we’ve been a little busy.

Just this week, we traveled back and forth between Austin and Houston several times, first to introduce a new cook at Prairie View A & M University’s Cooperative Extension annual State Conference and Awards Banquet, then, to install an exhibit at Project Row Houses, where the Blue Grass cooks will be on view for the next two months. In between, there were multiple event planning meetings and nursing a kid recovering from ACL surgery.

Oh my goodness.

Everyone warned me when I started this blog project over a year ago not to put myself under pressure to be brilliant or witty on demand, like pay-per-view. But I am a journalist, for Heaven’s sake! I require a deadline to stay on task. Besides, as far as Jemima tales are concerned, I could go on and on and on.

So what a surprise that after my trip to the White House for Chefs Move, I didn’t go on at all. Instead, I stopped researching new women and accepted way too many opportunities to serve the community — as chair of the host city committee for the 33rd annual conference of the International Association of Culinary Professionals, and vice president for Foodways Texas, a new organization modeled after Southern Foodways — all while teaching kids to like the taste of kohlrabi everyday after school. The University of Texas honored the nonprofit cooking organization I founded with a service award for all of those healthy kiddy cooking classes, but my heart beat louder and louder for more Jemima tales.

What would you do? What Jemima would do, of course.

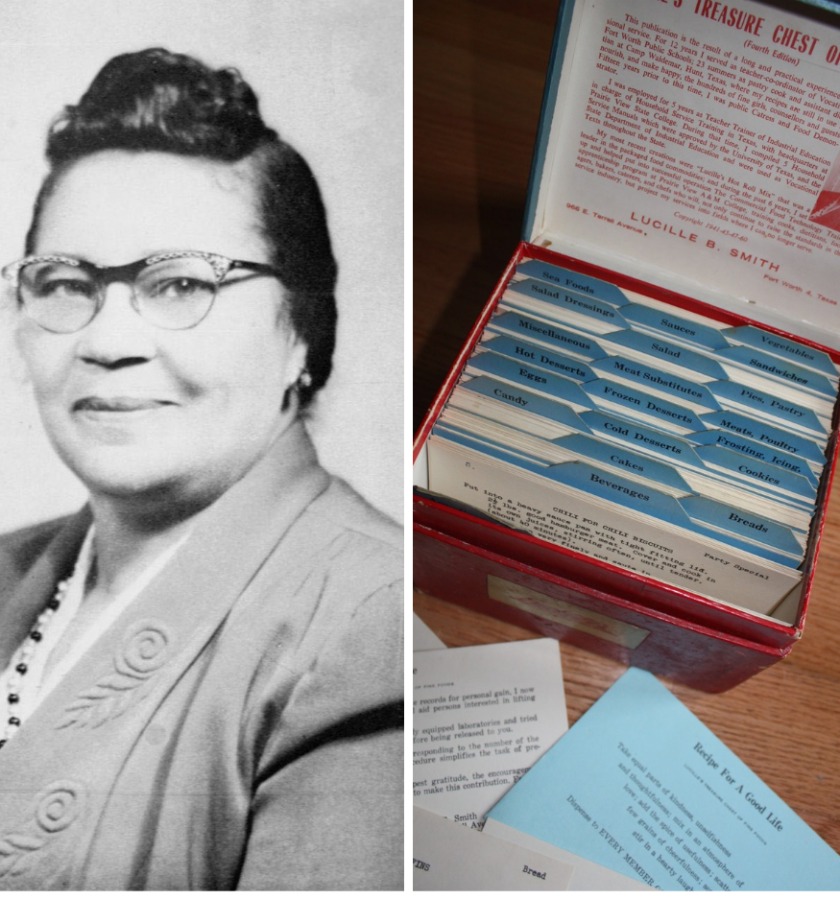

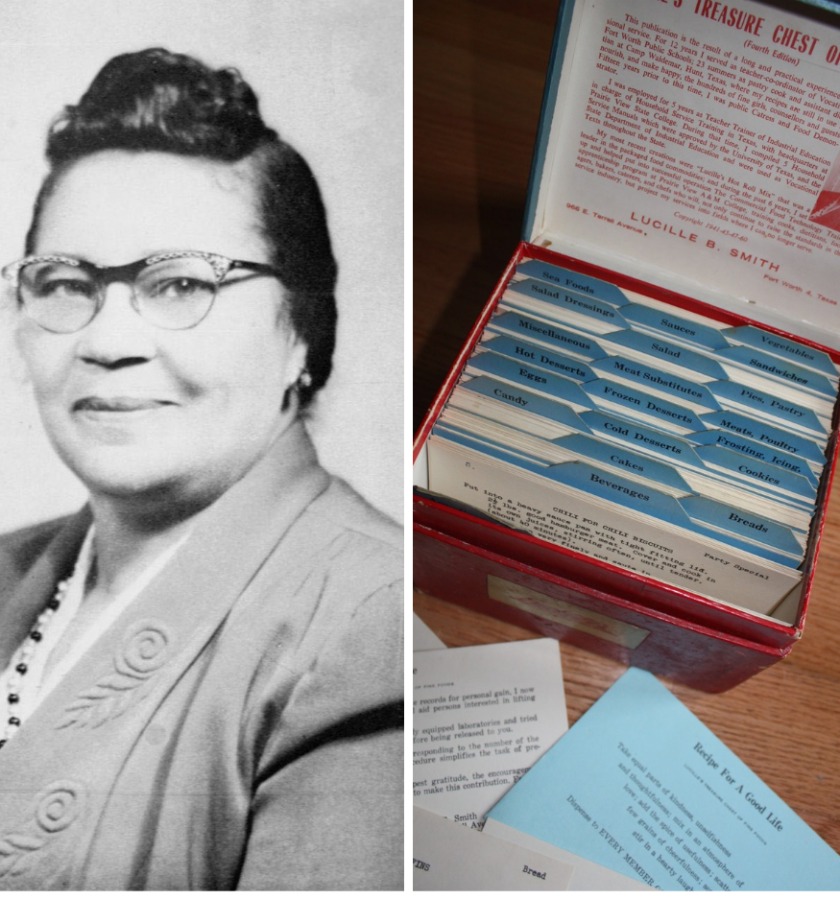

I started sharing “my girls” with live audiences too, presenting Jemima as a role model at meetings of the Culinary Historians of Southern California, the National Forum for Black Public Administrators, and Slow Food Austin. I also told a grateful Prairie View audience about an inspirational woman with an inventory of professional culinary accomplishments and community work so long the city of Ft. Worth honored her with a day named just for her. Her name was Lucille Bishop Smith.

This was a good week for Lucille’s whispered wisdom.

For me, this Tarrant County native upheld the African American cook’s nurturing character while teaching the value of discipline, confidence, and creative thinking during difficult times. Not coincidentally, her profile demonstrated numerous ways that organizational, technical, and managerial skills can be added to the profile of American black cooks.

Lucille lived productively, establishing herself as a respected professional with a local and state reputation during the Great Depression, and publishing more than 200 delicious recipes for simple, as well as elegant cookery, in Lucille’s Treasure Chest of Fine Foods. She raised funds for community service projects, fought to raise standards in slums, developed culinary vocational programs in Ft. Worth and at Prairie View, was responsible for the first extension workers being employed in Tarrant County, brought the first packaged Hot Roll Mix to market, conducted Itinerant Teacher Training Classes, developed Prairie View’s Commercial Cooking and Baking Department, compiled five manuals for the State Dept. of Industrial Education, and was foods editor of Sepia Magazine. And all of that is just part of her resume. Her bio concludes:

“She represents a faithful wife, a devoted mother; a devout Christian, a character builder, a successful business woman, a pioneer in education ventures and a dedicated servant of people.”

Lucille’s Treasure Chest epitomized her life’s work to empower others by using food as a tool to achieve social uplift. In the Preface, she encourages women of the community to follow in her footsteps with this Recipe For A Good Life:

Take equal parts of kindness, unselfishness and thoughfullness;

mix in an atmosphere of love;

add the spice of usefulness;

scatter a few grains of cheerfulness;

season with smiles;

stir in a hearty laugh, and

Dispense to EVERY MEMBER OF YOUR FAMILY

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 7, 2010 | Entrepreneurs

With Tiger Woods back in the news this week, my thoughts immediately turned to Fuzzy Zoeller’s yakity yak urging Woods not to “order fried chicken or collard greens…or whatever the hell they serve” at the 1997 Masters golf tournament champions dinner. Zoeller might have been one of golf’s most notable players, but he obviously missed the memo on African American culinary tradition.

For generations, African American cooks living outside of the South have enjoyed confident, creative culinary expression, preferring to be known for their artistry, rather than the narrow outlook that limits the African American cook’s repertoire to the poverty ingredients and methods of plantation cabin cookery.

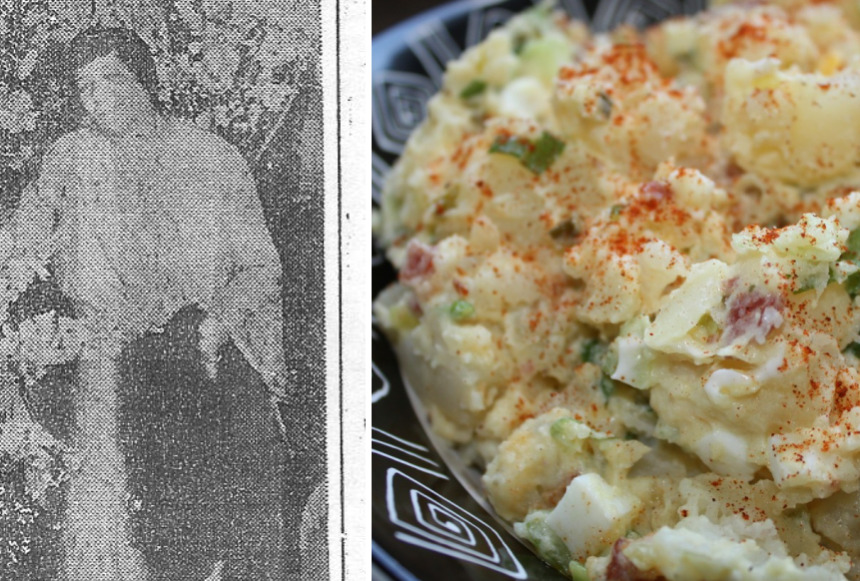

In 1910, while the domestic scientists were analyzing their food, “draining it of taste and texture, packaging it, and decorating it” to accommodate their shifting emphasis to domestic efficiency, Bertha Turner, a State Superintendent of Domestic Science and private caterer published a remarkable cookbook to preserve black culinary identity.

The Federation Cookbook: A Collection of Tested Recipes Compiled by the Colored Women of the State of California, assembled delicious recipes from the noted cooks living in and around Pasadena. The book exemplified a type of culinary professional who survived blatant discrimination and achieved fame and success.

By coincidence or Divine Order, Turner’s kitchen priorities and caterer’s virtues of uniformity, familiarity, and predictability perfectly aligned with the domestic science movement’s institutional ambitions of standardization and technical know-how. She was also a very good cook, according to the obituary published in a 1938 local newspaper, which also carried this photo of her, dressed elegantly and draped in fur.

She lived prosperously, flourishing in the rich ethnic culture of the Pasadena foothills, and didn’t appear stifled by the Jim Crow ideology strangling her race elsewhere. In fact, her Federation Cookbook set off confidently – perhaps because it epitomized a resolute gathering of out-going, successful women dedicated to social uplift.

Unlike Abby Fisher and Malinda Russell who began their books apologetically, Turner gracefully promised in her Preface to deliver “tested cooking of tried proportions, kindly given by our women.” She boldly suggested that readers purchase the book to thank those “helpful, trusty” women whom she memorialized in every recipe.

“Take it to your friends and neighbors,” she urged. “May it prove a blessing to you.”

Turner probably was obviously a compassionate woman, too. The Federation Cookbook began with a cheerful poem composed by a member of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, to shore up young cooks. She shared more than 200 recipes for simple, as well as elegant cookery, including numerous ways with lettuce, gelatin, and molds – the “dainty” delights popular among domestic goddesses at the time.

Interestingly, the only Southern dishes to survive the trip West with this regal, Kentucky-born patron were croquettes, okra, and cornbread.

Does that answer your question about what we serve, Mr. Zoeller?

*

In Bertha Turner’s day, homemade salad dressings, including mayonnaise were evidence of a cook’s proficiency. The mix is simple: eggs, good quality oil, vinegar or lemon juice, and salt and pepper to taste. With today’s rush through the kitchen, you can achieve potato salad with the same creamy results using commercial mayo and a splash of prepared mustard.

In Her Kitchen

Potato Salad

Ingredients

- 4 slices bacon

- 8 new potatoes

- 5 hard-boiled eggs, peeled and coarsely chopped

- 3 green onions, sliced

- 2 stalks celery, diced

- 1/4 cup sweet pickle relish

- 1/2 cup mayonnaise

- 1 tablespoon mustard

- Salt, pepper

- Paprika

Instructions

- Cook bacon in a hot skillet over medium heat until crisp. Cool and crumble. Set aside. Scrub the potatoes and boil in their jackets until just done. Cool, peel and dice. Place in a large bowl with eggs, onions, celery, and pickle relish. Stir in mayonnaise and mustard, and season to taste with salt and pepper. Sprinkle with paprika before serving.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 17, 2010 | Entrepreneurs

As a journalist at a bloggers workshop, I was feeling a little bothered while attending South by Southwest Interactive (SXSW) this week, like a wolf in sheep’s clothing, until I realized that the women who inspire me also lived as if there were four of them.

They published cookbooks. Operated retail food businesses. Invented culinary gadgets. Hawked food products. Taught home economics. Catered lavish events. Sometimes, all at once.

As an author, I loved getting to know Abby Fisher and Malinda Russell, and imagining the kind of intelligent and creative recipes that my ancestors might have published if given the opportunity.

This week, I find muse in Kentucky, looking for the perfect mint julep to serve at a catered event next month, where I will be speaking about and teaching southern food traditions, and maybe making a dish or two.

Who me? Multi-task?

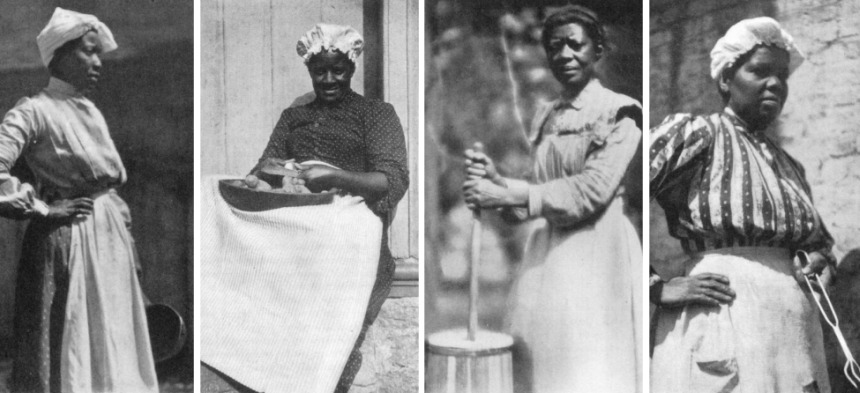

The first artifact is The Blue Grass Cook Book, by Minnie C. Fox.

Although it was not written by a black cook, the University Press of Kentucky and I published the historic reprint of Blue Grass in 2005 because it is the first-known cookbook to offer an honest and revealing picture of the state of culinary affairs in the South at the start of the twentieth century. It features more than 300 recipes and a dozen stunning camera portraits – not caricatures – of African American cooks at work. They are pictured above.

More directly than anyone before them – or after, until mid-century – Minnie, and her novelist brother John, publicly acknowledged the black contribution to Southern foodways, Southern culture, and Southern hospitality in 1904. In what amounts to direct and explicit homage, Minnie applauds the “turbaned mistress of the kitchen” for her dignity, wisdom, and talent.

This picture casts a bold shadow of hope and grace on the Aunt Jemima make-believe.

John Fox’s introduction and the photographs of Alvin Langdon Coburn do for these great cooks what historians, cookbook authors, novelists, advertisers, and manufacturers simply did not: They single out for full recognition and credit the black cook as the near-invisible but indispensable figure who made Southern cuisine famous.

Meanwhile, as housewives produced textbooks that emphasized the technical basics of cooking at the turn of the twentieth century, Effie Waller Smith wrote poetry that made powerful statements about the competencies of her African American sisters in the kitchen.

The authority and observations in her collected works, which were discovered and republished by the Schomburg Library in 1991, include interpretation, so I’ve simply included my favorite poem here for you to enjoy, and hopefully to share.

Maybe next time, I’ll attend a meeting of anthropologists.

APPLE SAUCE AND CHICKEN FRIED

By Effie Waller Smith, 1904

You may talk about the knowledge

Which our farmers’ girls have gained

From cooking-schools and cook-books

(where all modern cooks are trained);

But I would rather know just how,

(Though vainly I have tried)

To prepare, as mother used to,

Apple sauce and chicken fried.

Our modern cooks know how to fix

Their dainty dishes rare.

But, friend, just let me tell you what!–

None of them compare

With what my mother used to fix,

And for which I’ve often cried,

When I was but a little tot,–

Apple sauce and chicken fried.

Chicken a la Francaise,

Also fricassee,

Served with some new fangled sauce

Is plenty good for me,

Till I get to thinking of the home

Where I used to ‘bide

And where I used to eat, — um, my!

Apple sauce and chicken fried.

We always had it once a week,

Sometimes we had it twice;

And I have even known the time

When we have had it thrice.

Our good, yet jolly pastor,

During his circuit’s ride

With us once each week gave grateful thanks

For apple sauce and chicken fried.

Why, it seems like I can smell it,

And even taste it, too,

And see it with my natural eyes,

Though of course it can’t be true;

And it seems like I’m a child again,

Standing by mother’s side

Pulling at her dress and asking

For apple sauce and chicken fried.

Author’s Note: Use caution if you purchase The Blue Grass Cook Book from Amazon. Applewood Books is offering a reprinted copy that does not include my historical background on the Fox family. If you would like to purchase an autographed copy of The Blue Grass Cook Book, please email me.

Comments