by Toni Tipton-Martin | Nov 8, 2011 | Domestics

It is Day 3 of a quick get-away to New Orleans and I am hopping over heaving sidewalks and the mammoth roots of heritage oaks as I jog toward the urban oasis known as Audubon Park in Uptown when up ahead, of all things, I encounter The Help.

Now, instead of the calming anticipation of an escape from the Texas heat and draught, I’m a little grumpy thinking instead about the movie the New York Times described as a “big, ole slab of honey-glazed hokum.”

Again.

The problem is this: Though slightly distorted by the mist of a steamy humid morning, I can see a narrow black woman in uniform as she emerges from a dilapidated Chevy. She waves goodbye to the elder lady behind the steering wheel, makes her way up the cobblestone walk and knocks on the door of an opulent southern mansion. As I jog by, I extend morning greetings to them both and realize that while I have been straining to hear the voices of accomplished Louisiana cooks over the loud and unrelenting gaggle surrounding the record-breaking book and film, real women of color are still reporting to work in the homes of wealthy families in these “post racial” times.

That reality is one of the truths about the complex relationship between American domestic workers and their employers flooding my recent thoughts with the unrestrained fervor of floodwaters from Lake Pontchartrain. And I am not the only one thinking this stuff.

An internet title search of Kathryn Stockett’s exploration of domestic race relations revealed a diverse range of opinions, several fascinating character studies, an open letter to fans posted by the Association of Black Women Historians and a thoughtful review by Audrey Petty in the Southern Foodways Alliance newsletter that compares The Help to a historically accurate text published at the same time, by Rebecca Sharpless entitled, Cooking in Other Women’s Kitchens, Domestic Workers in the South, 1865-1960.

But, it was the broad sweep of reactions I observed at a University of Texas roundtable comprised of Austin students, community members and scholars who gathered to answer the question “What Are We Going to Do About the Help?” that galvanized my resolve to stop fretting about this tiresome fiction and do something productive: Focus on giving life to the unnamed women who really did do America’s cooking in The Jemima Code – The book.

While African American historians and critics are rightly troubled on numerous levels, white audience members seem surprised and even offended by their furor. Whichever side of the debate you are on, one reality is easy to defend: Aibiliene and Minny have stirred a race and food dialogue that gives Jemima Code cooks the opportunity to tell their own sweet, long-suffering truth not just in academia, but with empassioned Americans, too. Finally. Too bad their book won’t be on shelves in time for the holiday DVD release of the film, which is sure to prolong the negative discourse.

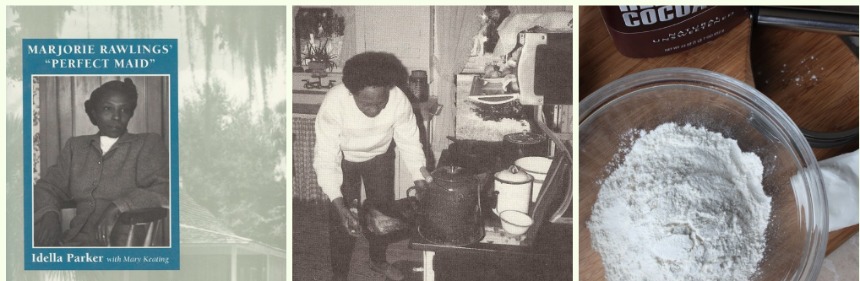

Thankfully, while we await the book, we can learn from Idella Parker.

Although her autobiography does not contain recipes in the traditional sense, Idella’s story accomplishes something unique and wonderful that continues to elude focus groups and institutional reconciliation efforts, scholarly works, well-intentioned cookbooks, and fiction like The Help with its fanciful domestic vibe. Parker draws everyone into the kitchen, inviting them to cook for each other and to persevere through awkward conversations about race when she describes what it was really like to be Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings “Perfect Maid” — a notion the Delany Sisters called, “Having Our Say.”

In 1992, at about the time that I began shopping the idea of The Jemima Code to academic and trade publishers to give voice to the unheard, this former domestic, teacher, and cook was going to press with an ambition similar to mine: telling her own account of life in the household of a popular American novelist.

“Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings called me “the perfect maid” in her book Cross Creek,” Parker wrote in the Preface to Idella, Marjorie Rawlings’ Perfect Maid. “I am not perfect and neither was Mrs. Rawlings, and this book will make that clear to anyone who reads it.”

Parker crafts an insightful look into the complex chemistry that existed between a black cook and her mistress in the late 1930s from memories that are believable, poised, and fair. As the story of their life together unfolds, we hear how it felt to be underpaid and overworked, and of Idella’s courage in the face of blatant racism.

And she is frustrated by this, also: after months together in the kitchen testing recipes for the cookbook, including many that were hers such as the chocolate pie, Idella is given credit for just three of them, including the biscuits.

Nearly 20 years later, fans still rave about Rawlings and her Cross Creek Cookery in reviews, while black cooks stare down jocular characterizations that portray them in aseptic stereotypes that trace back 100 years. In the final words of her autobiography, Idella describes the paradoxical situation like this:

“Our relationship was an unusually close one for the times we lived in. Yet no matter what the ties were that bound us together, we were still a black woman and a white woman, and the barrier of race was always there.

“In private, we were often like sisters, laughing and chatting and enjoying one another’s company. We shared many years together, helped one another through bad times, and rejoiced for each other’s happiness. Between the two of us there was deep friendship and respect, and no thought of the social differences between us.

“But whenever other people were around, the barrier of color went up automatically. Without acknowledging that we were doing so, we became more distant to one another. She became the rich, white lady author, and I became quiet, reserved, and slipped back into her shadow, ‘the perfect maid.’”

Funny thing is, with truth such as this, Parker just doesn’t come off like the kind of woman who would retaliate for bad times by putting shit in the mistress’ chocolate pie.

Would she?

In Her Kitchen

Cross Creek Chocolate Pie

Ingredients

- 1 cup milk

- 1/2 cup granulated sugar

- 1/4 cup all-purpose flour

- 5 tablespoons cocoa powder

- 1/8 teaspoon salt

- 2 eggs, separated

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- 1 (8-inch) baked pie crust

- 1/4 cup powdered sugar

Instructions

Scald the milk in the top of a double boiler. Combine the granulated sugar, flour, cocoa, and salt and whisk into the milk. Beat egg yolks lightly. Stir in the yolks and cook, stirring constantly, until the mixture is well thickened. Remove from heat and cool slightly. Stir in 1/2 teaspoon vanilla. Pour into the baked pie crust. Beat egg whites to soft peaks. Gradually beat in powdered sugar and remaining 1/2 teaspoon vanilla. Beat until stiff peaks form. Spoon meringue onto chocolate filling and bake at 325 degrees 20 minutes, or until lightly browned

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | May 28, 2011 | Domestics

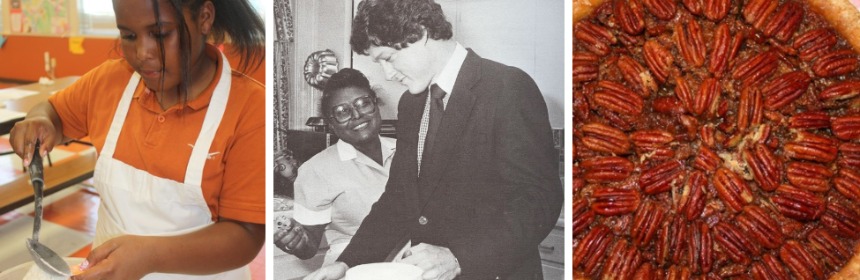

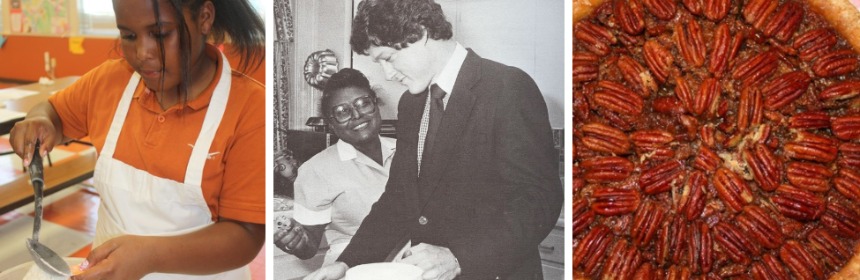

Ask the children in my Garden to Table cooking and nutrition class why we gather together daily after school, while elsewhere in the city other kids are at home watching T.V. and hanging out with friends, and these ebullient third through fifth graders will shout with confident pride: “To get healthy, not skinny!”

For about a year, as part of the WellNest at the University of Texas Elementary School, 20 students have grown and maintained organic vegetable gardens, played games that were as much fun as MarioKart, learned about the MyPyramid groups and figured out how to read food labels. They also took away a few intangible values that should help them lead healthy, productive lives defined by good character and common sense — all while cooking their own snacks from whole grains, fruits and veggies. They just didn’t know it.

So when children’s cooking instructor and cookbook author Michelle Stern and I met at the White House last summer (we were among the chefs invited to join the First Lady’s launch of Chefs Move to Schools), and she invited Garden to Table to be part of a workshop she was planning, I jumped at the chance for these kids to show off their culinary smarts and mastery of some very basic life skills. Months later, when Bill Yosses, the White House Executive Pastry Chef agreed to join the event, my meeting Michelle seemed more than serendipitous — it was Heaven sent.

Garden to Table teaches this eager bunch that there are no good or bad foods and that balance and moderation are lifetime goals they should strive to achieve. I confess to them that I too was a fat kid with an insatiable sweet tooth. I didn’t exercise very much at all. And, yet today, I live a mostly healthy life, jogging or swimming daily, passing up foods that don’t really matter that much to me, and saving my calories for goodies that I really love — like Champagne and chocolate. We also learn to respect one another while practicing table etiquette.

The prospect of introducing them to the man whose baking talents make the President of the United States just as nervous about diet as they are was, well, delicious.

Last Spring, David Axelrod, Obama’s senior advisor, told Jay Leno that the President was forced to “separate” from the White House pastry chef to break his bad eating habits. The President’s “pie problem” story was reported in the Huffington Post.

“One of the things that happened when he came to the White House is they have a very great pastry chef. It became a big problem,” Axelrod confided on “The Tonight Show.”

President Obama isn’t the first president to be taunted by the cook’s pie. During his years in the Arkansas Governor’s mansion, President Clinton felt just the same — allured by chess pie. It was made by a woman whose image hangs in the Jemima Code’s gallery of great cooks, Liza Ashley, author of Thirty Years at the Mansion.

Growing up, Ashley developed a passion for cooking while she followed her grandmother around at work on Oldham Plantation where she was born. As she matured, habits of self-control, courtesy, confidence and time management blossomed. She even led a food service team that at one point relied on inmates to get the kitchen work done.

“Ashley is an historic figure,” wrote Bill, Hilary and Chelsea Clinton, in the Introduction to the Clinton White House edition of this Classic Cookbook of Recipes, Recollections, and Photographs from the Arkansas Governor’s Mansion. “For three decades she has caused governors and their families to fight and lose battles of the bulge. Her years of service…have left their mark on history.”

Anyone who accepts the First Lady’s challenge knows that teaching kids cooking and nutrition can be rewarding and fun. It can also be a lot of work. There are bureaucracies to navigate. School budgets are limited. And, sometimes, the kids would just rather go home and play.

If Ashley could be with us on June 1 at the Kids in the Kitchen workshop, at a gathering of chefs (including Chef Bill) at the Texas State Capital, and at a fundraising Pie Social hosted by SANDE on June 4 that will honor women like Ashley, she would do more than esteem our dedication to improved lives; she would model it.

*

For information about Chefs Move to Schools at the Texas State Capitol, or the Kids in the Kitchen cooking workshop at the University of Texas Elementary School and Whole Foods Market, check out the Conference highlights at iacp.com.

To learn about The SANDE Youth Project’s preservation project and Peace through Pie, our fundraising social and Juneteenth celebration, see the events listing at: thesandeyouthproject.org.

In Her Kitchen

Bill Clinton’s Favorite Lemon Chess Pie

Ingredients

1/2 cup butter or margarine

2 cups sugar

5 eggs

1 cup milk

1 tablespoon flour

1 tablespoon cornmeal

1/4 cup freshly-squeezed lemon juice

Grated zest of 3 lemons

1 (9-inch) unbaked pie shell

Instructions

In the bowl of an electric mixer, cream together butter and sugar. Beat in eggs and milk. Beat well. With mixer running, add flour and cornmeal, alternating with lemon juice. Beat in lemon zest. Pour filling into pie shell and bake at 350 degrees for 35-40 minutes, or until center is set.

Number of servings: 8

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jun 2, 2010 | Domestics

This Friday when Michelle Obama welcomes top chefs and food professionals from around the globe to the White House to introduce the latest ingredient in her recipe for changing the food habits of America’s kids, the women of The Jemima Code and I will be among the privileged in chefs coats stirring the pot.

Through a partnership with food professionals’ organizations such as Share Our Strength, the National Restaurant Association, the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP), Women Chefs and Restaurateurs (WCR), and Les Dames d’Escoffier, chefs and cooking teachers will exchange ideas about increasing nutrition awareness as Mrs. Obama launches the Chefs Move to Schools program.

Her idea is simple really. Because chefs have a unique ability to deliver health messages in fun and creative ways, Chefs Move to Schools was created to challenge culinary experts to adopt a school and work with teachers, parents, school nutrition professionals and administrators to help educate kids about food and nutrition, according to the website, www.letsmove.gov.

Chefs Move will be operated by the Agriculture Department and will pair chefs with interested schools in their communities so they can create healthy meals while teaching young people about nutrition and making balanced and healthy choices. The White House assembly will include culinarians who want to join the campaign, as well as those who are already empowering children toward healthy, productive futures. Like me.

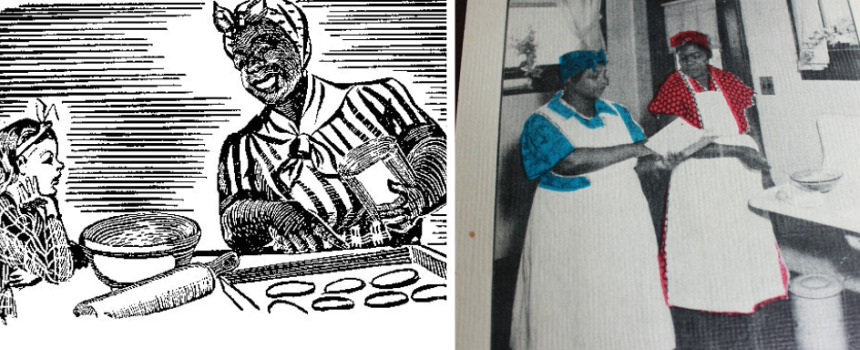

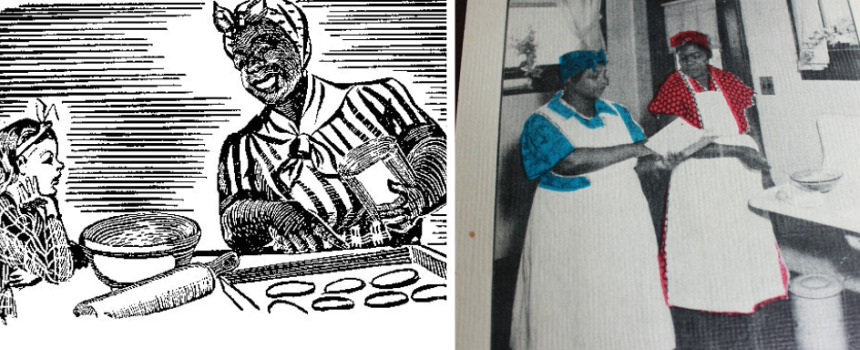

When I the built The SANDE Youth Project in 2008 after 25 years of using written words to teach readers about cooking and nutrition, I returned to the same foundation of oral tradition that my ancestors used to impart proficiency, morals, self-esteem and respect for the community to their children and the children of their employers. This illustration from Marion Flexner’s 1941 cookbook, Dixie Dishes, was published to keep black women in their place by contrasting the child-like housewife to a massive cook towering above. For me it simply proves that African American cooks have always been skilled culinary educators, whether credited for their knowledge or not. And that truth informs both my hands-on and written work.

Both SANDE and the women of The Jemima Code communicate important life skills and the tenets of healthy eating while making tasty recipes. Both teach by including the student in the process. And, both rely on age-old wisdom. The difference is that elementary school-age kids at SANDE learn from high school and college students.

The pilot program expands the Healthy Families Initiative at the University of Texas Elementary School through a community partnership with UT’s Division of Diversity and Community Engagement. The kaleidoscope of student-led gardening, heritage, and nutritious-cooking activities nourish and empower underprivileged families the way that Mrs. Obama’s Let’s Move campaign returns responsibility for the health of children to the community. It is a unique approach, also instilling 10 Core Values in the areas of Spirit, Attitude, Nutrition, Deeds, and Emotions (SANDE).

At SANDE, we hope to give kids a head start on healthy futures, at the kitchen table, one meal at a time. Students follow their food from seed to plate. They learn the importance of kitchen organization and safety. Develop the taste for food that is fresh and preservative- and additive-free. Discover that it is the raw egg that makes their favorite cookie dough unsafe to eat before baking. And, they gain literacy from reading recipes and writing their own cookbook while manipulating fractions and solving questions of chemistry. The kids are not, however, learning how to cook diet food.

After two hours pounding chicken breasts, grinding and toasting their own homemade bread crumbs, and shredding Parmesan cheese for chicken Parmesan, tasting a dozen green leaf varieties before assembling salad, and churning their own homemade ice cream, a group of giddy 10-year-olds hurries excitedly to set the table for lunch. One of the boys who came to class thinking that cooking was girly described the SANDE experience best when he stated:

“Man, I can’t believe I made this.”

A few bites later, he added, “I can’t believe this tastes so good.”

When lunch was over, he exclaimed: “I can’t believe I made this and that it tastes so good!”

Now that is what I’m talking about.

As encouragement to keep them cooking, I shared this tidbit from Aunt Julia and Aunt Leola, authors of Aunt Julia’s Cookbook, the Standard Oil Company of Pennsylvania’s 24-page collection of simple Carolina Low-Country recipes. The message seems especially fitting today.

“For Happy Eating Use These Recipes.”

by Toni Tipton-Martin | May 19, 2010 | Domestics

I didn’t mean to make anyone cry. Quite the contrary. I write thejemimacode to honor invisible women and to celebrate — as in party over here! But recently, more followers of this space are sharing intimate stories off-line of the women whose cooking made them feel special. Now, however, thinking about how unfairly the women were treated makes them terribly sad. Reconciliation can do that.

So, I’m here to cheer you up with news that after the hurt comes the heal, at least that is what we experienced following difficult dialogue at gatherings of the Southern Foodways Alliance. I also want to share the uplifting story of two women who came together to preserve the work of one of those obscure cooks in Rebecca’s Cookbook.

In 1942 while the world was at war, Rebecca West was traveling the country with her “lady” amassing a treasure-trove of receipts and recording her escapades in the local newspaper. That “lady,” known only by the initials E.P. helped West record dozens of dishes, from from terrapin to pate de fois gras, as well as childhood recollections of her visits to South Carolina and miscellaneous ruminations about the Bahamas.

Thankfully, E.P. did not resort to the demeaning Jemima stereotype when she transcribed West’s thoughts and recipes. Yes, West speaks in the broken English that is evidence of a rural upbringing, but she is not portrayed by the maliciously exaggerated speech we’ve seen in recent posts. No elitism here either. E.P. obviously respected West’s knowledge and talent, making no claims to her recipes and stating in a brief editor’s note that “Rebecca is so noted for her terrapin, that it is only right for terrapin to have a separate section all it’s own in her cook book.”

West also tells us a bit about their cozy relationship in numerous references to their experiences together in the kitchen. As the introduction to the Fish section, which features examples of modern cuisine such as red snapper fillets sauteed in olive oil, herbs and shallots, then braised in a tomato cream sauce; stuffed baked black bass; sauteed sea scallops; and scalloped oysters, West offers the following amusing tale.

“One night when my lady was out to dinner the butler came runnin downstairs all out of breath. He said, “The lady said she had the best fish tonight at dinner that she ever had an she wants you to try to fix somethin like it.” I says, “Now wait a minute, wait a minute. How does she know it was fish she was eatin?”

He says, “She said she could only see the tail of the fish stickin up out of a cream sauce an she don know what kind of fish it was, but it was good. You better figure out what it was, Rebecca.”

“So I got to figurin…I know the lady who does the cookin where my lady was havin dinner, so I says to the butler, “Joe you skip over there an ask her will she oblige me with the recipe for the little fish with cream sauce they had for dinner tonight…Just as I expected, the dish wasn’t made of little fish at all. It was ham. My lady was so surprised when I told her. She says, “That’s what comes of dinin by candlelight.”

Anyways here’s some receipts which is really fish…”

Precious, isn’t she?

Anyways, after a quick flash in a hot skillet, Rebecca layers red snapper fillets in a baking dish and covers with a cream sauce before baking. We don’t eat much cream at my house so I adapted Rebecca’s snapper to suit my family’s tastes and today’s demand for food that is light, fast and hassle-free. I started with my kids’ favorite way with spinach (lightly sauteed with a little garlic and onion), then used the mix as a bed for rolled and stuffed fillets. Rolling the fish is beautiful and makes dinner seem special. A quick steam, some hot cooked rice, and a healthy dinner is done. Thanks, my ladies.

In Her Kitchen

Red Snapper Roulades with Spinach

- 4 red snapper fillets, skinned and boned

- Salt, pepper

- 1/4 cup prepared spinach dip, about

- 1 tablespoon each olive oil and butter

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 large shallot, minced

- 1 pound fresh baby spinach, rinsed and drained

Instructions

- Season fillets lightly with salt and pepper. Place fillets skinned-side-up on a board. Spread each fillet with 1 tablespoon dip. Roll fillets to enclose dip, beginning with the widest end of the fillet. Secure fish rolls with a wood pick and set aside. Heat oil and butter in a large skillet until sizzling. Add garlic and shallot and saute until tender. Add spinach to the pan and cook about 5 minutes until wilted but still bright green. Place fish rolls on top of spinach. Cook, covered, over medium heat, 10-15 minutes, or until fish is no longer opaque. Remove wood picks before serving.

Note: Do not dry spinach leaves completely. The moisture from rinsing provides the steam that cooks the fish without over cooking the spinach.

Number of servings: 4

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | May 12, 2010 | Domestics

Everyone asks me the same question when I hand out my business cards:

“What did you think of The Help?”

Sheepishly, I admit that I haven’t read the best-selling novel. I can’t.

You should know that my calling card bears the image from this blog on the front, and a 1904 photo of a black cook on the back. That is because the women of thejemimacode are the backdrop of everything I do — from my writing and speaking to the nonprofit organization I’m building in Austin. I’ve spent so many years researching real domestic servants, that it is taking some time for me to warm to the idea of another fictionalized accounting of their lives. I’ll tell you why.

When I began this project I promised never to purchase any of the plantation cookbooks that degraded African American cooks with distorted images and vernacular language. Nor would I collect any of the “black Americana” kitchen collectibles featuring bug-eyed household servants as salt and pepper shakers, and on dish towels, spoon rests and the like. (My ambition is to collect artifacts that improve the image of African American cooks, not destroy it.) Trusted friends tell me that this new novel is fair and pleasant, but I have spent too many nights crying myself to sleep from reading slave narratives at bedtime to bankroll overt racism. I’m not saying The Help is bigotry; I’m just mustering the courage to see for myself.

My anxiety can be traced to the horror I experienced when I finally obtained a copy of Emma Jane’s Souvenir Cook Book And Some Old Virginia Recipes, Collected By Blanche Elbert Moncure, only to discover its encoded sentiments. I optimistically hoped that the shared by-line to this book represented an end to the common practice of recipe books published on behalf of black domestic workers deemed too ignorant to record their own recipes. And, I was pleased that the introduction to this 80-page collection included Jackson’s photo — not a cartoon — with this innocent characterizatization: “a good and faithful servant who has lived in the writer’s family for over 50 years.”

Jackson, a real woman? Yes.

Moncure, her advocate? Probably not.

From here, Moncure went on to tell a fanciful tale about how Jackson came to be known by the name printed as the cutline beneath her portrait: Emma Jane Jackson Beauregard Jefferson Davis Lincoln Christian. She followed the wistful tale of Civil War soldiers and “the little nigger baby” with Emma Jane’s culinary advice to the bride-to-be derisively:

“Well, Miss Sally, I sho‘ gives you all of my complements an‘ good wishes! Fur, when a young lady laike you is, begins to compensate matimony, de very bes‘ path she can take is dat one dat leads straight to de kitchen…But look here! Why is you a comin‘ to me, fur de informity? I aint no cookin‘ teacher! I is jes a plain uneddicated cook-o’man, what can’t even read her own name, much less a ‘ceat book! You have to go to college an‘ ‘tend dose Messy Sciences Classes dese days, to be what you calls a fuss class cook! So don’t come in dis kitchen, effen you wants to be in de fashion…Of cose, I been cookin’ fur a purty long time when you come to think of it…I recon I ought to be able to give you some ‘vice ennyways, what may come in handy — dat is — effen you lissins to it.”

I was not dismayed by the familiar storyline, but did I want it as part of my library? Did I enjoy reading it for entertainment? Not so much. What I did do was manage to distill a few bits of Emma Jane’s culinary wisdom and some of her thoughts about locally-sourced, seasonable foods, the way that the women of my muse prepared nourishing meals from discarded garbage. I’ll paraphrase.

- We eat first with our eyes, so always pay attention to the table, whether it is just a plain pine kitchen table or a shiny mahogany table dressed with fine lace and candles. A floral centerpiece is good for digestion. The sight of it is good for sore eyes.

- Making biscuits is easy, but pay attention! Have that oven hot. And I mean hot before you put those biscuits in there. A cold oven is responsible for more brick “bats” than most people think. The poor bride is blamed for it all, when in fact the oven is more to blame.

- Some folks serve stewed oysters for breakfast down in this part of the country, but try to get them as fresh as you can for they can “kick up Hally-lu-ya” (make you sick) if they are old. Of course, the winter months are the best time of year to get the most flavorful taste. In the summer, they are poor and milky-like.

- Don’t go to the store for your holiday turkey. They aren’t fit to eat. Go to a dependable person who knows his business (know your farmer) and let him pick, slaughter and prepare a plump hen for you. Half your preparation troubles will be over.

Maybe The Help won’t hurt after all.

What were your thoughts after reading it?

In Her Kitchen

Emma Jane’s Buttermilk Biscuits

Ingredients

- 3 cups all-purpose flour

- 1 tablespoon baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 cup lard, cut into pieces and chilled

- 3/4 to 1 cup buttermilk

Instructions

- In a large bowl, whisk together the flour, baking powder, soda and salt. Cut the lard pieces into the flour mixture using two knives or a pastry blender until mixture is crumbly and lard is evenly distributed. Using a fork, stir in the buttermilk, adding just enough to make a slightly sticky dough. The amount may vary because buttermilk is thicker than milk. When dough pulls away from the sides of the bowl, pour out onto a lightly-floured board. Sprinkle with a small amount of flour and knead the dough about 10 times to make a light dough. Do not add too much flour or handle too much. Pat dough into a 1/2-inch thick disc (or use a rolling pin). Cut with a floured biscuit cutter. Place on a shiny baking sheet, about 1/4-inch apart, or in a baking pan just barely touching. Do not re-roll scraps. Gather into one biscuit or scatter the leftover pieces on the pan and serve as a snack. Bake in a preheated 450 degree oven 10 minutes or until light golden brown. Let cool 5 minutes before serving.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

Comments