by Toni Tipton-Martin | Dec 9, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

My grandmother Nannie was a sturdy woman of Choctaw decent who cooked the most delicious food, but she passed on without leaving me a single morsel of the culinary wisdom and life lessons my mother’s generation took for granted. And, yet, her raspy voice of affection still whispers two things to me: security and chocolate cake.

My family spent the years before I turned six, living with Nannie in her modest two-bedroom home. When I wasn’t perched on the branches of the towering avocado tree that shaded Nannie’s backyard like a 100-year-old oak, I was being lured into her kitchen by the intoxicatingly sweet cocoa perfume of a bubbling mixture as it percolated in the top of her Pyrex double boiler. Nannie saw my desperate anticipation for even a tiny taste, wiped her hands on the yellow gingham apron her twin sister Jewel had sewn for her – the one with the torn pocket and border of delicate garnet strawberries – leaned forward and handed me the bowl. I don’t remember much about the cake, but raw batter still seduces me today. And, the memory makes me feel warm, comforted, and strangely secure, even though I’m not a little girl anymore.

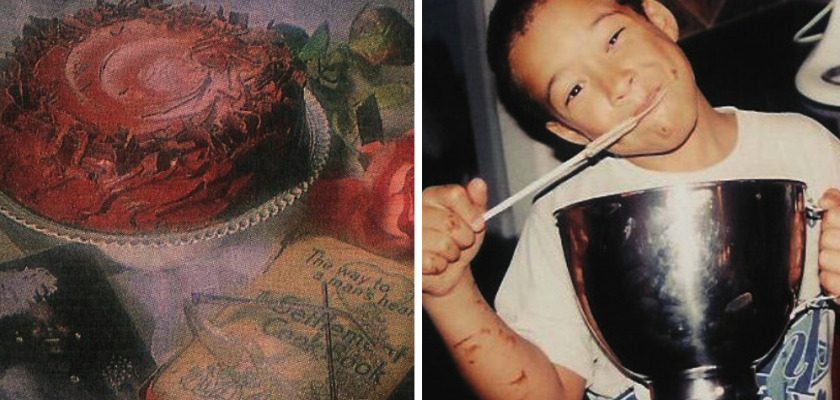

Several years ago, we developed a recipe and this photograph for Nannie’s Devil’s food cake in the Los Angeles Times’ Test Kitchen, which first brought the memories of her kitchen flooding back. Basking in the warmth of those special moments made me realize that many of my memories at the table with Nannie had been suffocated. Somehow over the years, I lost touch with the woman who would have been my very own personal culinary counselor, helpmate, and role model. Even with all that I knew about kitchen skill and kitchen dirty work, and “practice makes perfect,” I still developed the wildy unrealistic view of her as some kind of “kitchen magician.” I got caught up in the notion that she was a natural-born culinary genius to be iconized, not a specialist to emulate.

A list of culinary cues from Nannie’s kitchen should have revealed a remarkable competence and told me that she cooked with her head, as well as her heart and her senses. In her kitchen, fingertips were the preferred instruments to measure a teaspoonful. She didn’t need the latest silicon-coated kitchen timer to tell her when it was time to turn the fried chicken; she knew just by the gurgling sound coming from the skillet. The sweet perfume wafting from the oven signaled that the pound cake was done baking. And, she scrambled delicate eggs in cast iron without any back up from Teflon. Instead, thinking about her intimidated me.

So I decided to make the cake again, following the yellowed recipe she tore from a magazine, and buried in the back pages of her favorite cookbook. It turns out the cake I naievely thought Nannie just whipped from her imagination, came from the Noble-Purefoy Hotel in Anniston, Alabama — a decadence that was lovely to look at, but its dense cocoa layers didn’t translate well into this century. Too many years of eating commercial birthday cakes, hurry-up cake mixes, and bakery goodies, I guess.

Nannie is gone and I’m still perfecting her recipe, and I adapted this Double Chocolate Fudge Cake from different recipes for fudgey pound cakes as a decadent conversation starter that lets me tell my kids about Nannie and the other members of her humble sorority. Now, my boys lick the beaters and the bowl clean.

In Her Kitchen

Double Chocolate Fudge Cake

Ingredients

- 5 ounces unsweetened chocolate

- 2 cups sifted all-purpose flour

- 1 teaspoon baking soda

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 cup instant coffee or espresso

- 2 tablespoons boiling water

- 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons cold water

- 1/2 cup orange rum

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- 1 cup unsalted butter

- 2 cups sugar

- 4 eggs

- Shortening

- Unsweetened cocoa powder

- Bittersweet Chocolate Glaze

Instructions

- Melt the chocolate in the top of a double boiler set over hot, not boiling, water. Remove chocolate before it is completely melted and stir until smooth. Set aside off heat.

- Stir together flour, baking soda and salt and set aside. In a 2-cup measuring cup, dissolve the instant coffee in the boiling water. Stir in the cold water, rum and vanilla and set aside.

- In the bowl of an electric mixer, cream together butter and sugar until mixture is light and fluffy. Beat in eggs, one at a time, beating well and scraping down the sides of the bowl after each addition. With machine running, gradually pour chocolate mixture down the sides of the bowl and beat until smooth. Add flour and coffee mixture to batter in 3 batches, beginning and ending with flour. Beat until smooth, but do not overmix. Batter may look slightly curdled.

- Grease a 10-cup bundt or tube pan and dust with unsweetened cocoa powder. Bake at 325 degrees 1 hour and 10 minutes, or until a wood pick inserted in the center comes out clean. Do not overbake.

- Cool cake on a wire rack for 15 minutes, then invert onto another rack to cool completely.

- Drizzle cake with Bittersweet Chocolate Glaze.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

In Her Kitchen

Bittersweet Chocolate Glaze

Ingredients

- 12 ounces bittersweet chocolate, broken into pieces

- 7 tablespoons hot water

Instructions

- Melt the chocolate in the top of a double boiler set over hot, not boiling water. Stir until smooth. Whisk the water into the chocolate all at once, whisking until the chocolate is smooth and shiny. It will have the texture of softly whipped cream.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Nov 26, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

By the time I was 30 years old, I could count my Southern life experiences on one hand. When you grow up in a tiny family in Los Angeles, sheltered by expatriates who left skid-marks when they quit the South, it is easy to believe that your family drama does not play east of the San Bernardino Valley. As children of the civil rights era, we lived in exile – sheltered from the narrow perspective of Negro subservience and proper place, liberated from the burden of low-class living. My parents built new and improved lives in the sands of the Pacific.

Not that the social, cultural, or culinary dimensions of Southern living were unrecognizable out West. Sweet tea and fresh-squeezed lemonade washed down Aunt Jewel’s crisp fried chicken, smoked pork bones seasoned Nannie’s Sunday greens, and Mother always baked her cornbread in a big, black cast iron skillet. But that was just dinner; everybody we knew in the middle class community of Baldwin Hills ate that.

I didn’t care all that much for pork ribs and became easily nauseated by the potent smell of chitlins that blasted through the air like a dragon’s fiery breath every time our neighbors from Tennessee opened their front door. Perhaps the most arresting evidence of my Western upbringing was my unapologetic admission that I sprinkled sugar on my grits.

As far as I could tell, precious few of my culinary notions qualified as Southern banners, and it was entirely possible that I would stumble blindly through the rest of my life without ever discovering the Aunt Jemima spirit living in me, if it hadn’t been for Vera Beck.

Vera resembled one of those African American matriarchs who once upon a time were thought of as saints – a woman in her twilight years whose culinary expressiveness was like a gift she bestowed upon the people she loved.

Whenever I think of her – and it’s often – I see a proud, generous, loving, tenderhearted, talented, exceptional cook. She made the best cornbread, chow chow, fried green tomatoes, and Mississippi mud cake I ever ate. And, although she earned her living as my test kitchen cook at one of the few major daily newspapers that dared to preserve the tradition, she was self taught and followed recipes handed down by word of mouth through generations of rural Alabama cooks.

Hers was a tradition that was less instinct and more five senses, but skill nonetheless; one that earned respect from the likes of well-known American cooking authority James Beard, and one that has all but disappeared among contemporary cooks.

As I got to know Vera better, she forced me to circle back and confront the peculiarity Virginia Woolf described as contrary instincts. I thought I was contented – a thirty-something food editor living far away from home on the eastern shore of Lake Erie, enjoying amazing and exotic world cuisine – the daughter of a health-conscious, fitness-crazed cook whose experiments with tofu, juicing and smoothies predated the fads.

In the few short years we had together at the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Vera taught me a few life lessons while showing me the way to light and flaky buttermilk biscuits.

She confirmed what I already had begun to fret about: that growing up as I did – outside the counsel of competent cooks who dispensed first-hand kitchen wisdom the way they apportioned hunks of ham to their children from bubbling pots of collard greens – made me an unfortunate casualty of the cruel social conditioning I call the Jemima Code.

While it is correct that black women did much of the cooking in early American kitchens, it is also true that they did so with the grace and skill of today’s trained professionals, transmitting their astonishing craft orally, from generation to generation.

When we consider the work accomplished by Vera Beck and generations of obscure cooks just like her, we should see a nearly extinct breed that honed their kitchen skills the way culinary students do today: by observation and apprenticeship. They expressed both art and skill when they cooked. They made do, certainly, but they also seasoned our lives and made our existence pleasurable – even under the most adverse circumstances. They cooked our meals from scratch, sewed our clothes, salved our wounds, nurtured our spirits, and imparted wisdom over a steaming plate of nourishment – and they did so while miraculously maintaining jobs outside their homes.

So, how is it that these are not the predominant images of African American cooks? Why don’t we celebrate their contributions to American culture the way we venerate the imaginary Betty Crocker? Why wasn’t their true legacy preserved? Can we ever forget the images of ignorant, submissive, selfless, sassy, asexual, despots? Is it possible to replace the mostly unflattering pictures of generous waistlines bent over cast iron skillets burned into our eyes? Will we ever believe that strong African women, who toted wood and built fires before even thinking about beating biscuit dough or mixing cakes, left us more than just their formulas for good pancakes?

I hope so.

In Her Kitchen

Cornbread with Cheese and Chiles

Ingredients

- 2 cups yellow cornmeal

- 1 tablespoon sugar

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 cup shortening

- 3/4 cup buttermilk

- 1 egg, beaten

- 1 (14.75-ounce) can cream-style corn

- 1 (4-ounce) can diced green chiles, drained

- 1/4 cup chopped green onion

- 1 cup shredded Cheddar cheese

Instructions

In a large mixing bowl, combine cornmeal, sugar, baking powder, soda and salt. Mix well. Melt the shortening in an 8-inch cast iron skillet. Pour shortening, buttermilk and egg into the dry ingredients and mix with a wooden spoon until just moist. Stir in the corn, chiles and green onion and pour half the batter into the hot skillet. Sprinkle with cheese. Top with remaining batter. Bake in a preheated 375 degree oven 30 minutes or until done.

Recipe and photograph courtesy of The Plain Dealer, 1978.

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Nov 20, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

I was privileged to meet Edna Lewis, the woman some have called the “Julia Child of Southern Cuisine,” in 1985 at the annual meeting of registered dietitians in Los Angeles, where she was drawing a crowd of autograph seekers. I was young and didn’t know a thing about her, but I purchased The Edna Lewis Cookbook, anyway, then for the next 10 years she silently mentored me as I cooked from its pages.

It wasn’t long before I was allured by her incredible talent and her delicate, selfless manner, just like the rest of the crowd. That’s why I was particularly surprised and humbled when her strongly-worded letter arrived in my office mailbox with a challenge: “Leave no stone unturned.”

It was 1995, and Edna was exhausted and weak from radiation, but she gathered her strength and composed a three-page rant about African American food history, which said in part: “We developed but did not own it [southern food] because we did not own ourselves,” Edna laments, “but we established a cuisine.

“Every group has its own food history,” Edna scribbled, with the kind of hurried penmanship that happens when thoughts are jumping out of your head and onto the page faster than you can capture them. “Our condition was different. We were brought here against our will in the millions, enslaved, and through it all established a cuisine in the south…the only fully developed cuisine in the country.”

Ten years later, after lost her battle with cancer at the age of 89, that letter became a personal treasure to me. It also made me sad. Edna’s culinary talent, authentic beauty, and quiet grace are cherished in the world of southern food. Elsewhere, she is virtually unknown.

Her words strengthened my resolve to celebrate the invisible women who fed America.

But, I knew it wouldn’t be easy. Julie, after all, had Julia; there just isn’t a single source that accurately portrays the history of African American cooks. In fact, if it had not been for Aunt Jemima stereotypes these tireless, talented women would have little written history at all.

Edna is just one of many affirming examples of real, professional empowered, beautiful – slim – black chefs who helped me re-think the link between African American women and the jarring portrait of the south’s “old black Mammy.” The powerful love language of their kitchens has taught me how to treat my children, how to give when my cup is empty, and of course, how to cook. And I mean really cook.

When I make Edna’s blackberry cobbler, my husband and kids each grab a spoon, stand around the steaming pan, and dig in, while I imagine her whispering the old-fashioned secret wisdom that used to be handed down between generations. I joyfully talk about the characteristics that intersect in the black women like Edna Lewis who fed this nation, but explain the ways they have been lost in lampoon. I discover that the woman I am becoming is a mere shadow of the women they were: patient and loving; smart, talented, hard-working; strong physically and emotionally, compassionate; multi-tasking.

I make peace with the harsh reality of my own double history, and that begins to break the Jemima Code.

I was privileged to meet Edna Lewis, the woman some have called the “Julia Child of Southern Cuisine,” in 1985 at the annual meeting of registered dietitians in Los Angeles, where she was drawing a crowd of autograph seekers. I was young and didn’t know a thing about her, but I purchased The Edna Lewis Cookbook, anyway, then for the next 10 years she silently mentored me as I cooked from its pages.

It wasn’t long before I was allured by her incredible talent and her delicate, selfless manner, just like the rest of the crowd. That’s why I was particularly surprised and humbled when her strongly-worded letter arrived in my office mailbox with a challenge: “Leave no stone unturned.”

It was 1995, and Edna was exhausted and weak from radiation, but she gathered her strength and composed a three-page rant about African American food history, which said in part: “We developed but did not own it [southern food] because we did not own ourselves,” Edna laments, “but we established a cuisine.

“Every group has its own food history,” Edna scribbled, with the kind of hurried penmanship that happens when thoughts are jumping out of your head and onto the page faster than you can capture them. “Our condition was different. We were brought here against our will in the millions, enslaved, and through it all established a cuisine in the south…the only fully developed cuisine in the country.”

Ten years later, after Edna lost her battle with cancer at the age of 89, that letter became a personal treasure to me. It also made me sad. Edna’s culinary talent, authentic beauty, and quiet grace are cherished in the world of southern food. Elsewhere, she is virtually unknown.

Her words strengthened my resolve to celebrate the invisible women who fed America.

I knew it wouldn’t be easy. Julie, after all, had Julia; there just isn’t a single source that accurately portrays the history of African American cooks. In fact, if it had not been for Aunt Jemima stereotypes these tireless, talented women would have little written history at all.

Edna is just one of many affirming examples of real, professional empowered, beautiful – slim – black chefs who helped me re-think the link between African American women and the jarring portrait of the south’s “old black Mammy.” The powerful love language of their kitchens has taught me how to treat my children, how to give when my cup is empty, and of course, how to cook. And I mean really cook.

When I make Edna’s blackberry cobbler, my husband and kids each grab a spoon, stand around the steaming pan, and dig in, while I imagine her whispering the old-fashioned secret wisdom that used to be handed down between generations. I joyfully talk about the characteristics that intersect in the black women like Edna Lewis who fed this nation, but explain the ways they have been lost in lampoon. I discover that the woman I am becoming is a mere shadow of the women they were: patient and loving; smart, talented, hard-working; strong physically and emotionally, compassionate; multi-tasking.

I make peace with the harsh reality of my own double history, and that begins to break the Jemima Code.

In Her Kitchen

Recipe: Edna’s Blackberry Cobbler

Ingredients

- 2 cups unbleached all-purpose flour

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 cup lard

- 1/3 cup cold water

- 1 cup sugar cubes, crushed

- 5 cups blackberries

- 4 thin slices butter

- 3/4 cups granulated sugar

- 2 teaspoons cornstarch

- 1/4 cup light cream

- 1 cup Vanilla-Flavored Whipped Cream (recipe follows)

Instructions

- Sift the flour and salt into a large mixing bowl. Blend in the lard with a pastry blender or with your fingers. When it is well blended and fine-grained, skrinkle in the water all at once, and draw the dough together quickly, shaping it into a ball. Divide in half and let rest a few minutes. Preheat the oven to 425 degrees. Roll out the dough and line an 8-inch baking pan. Sprinkle 2 to 3 tablespoons of the crushed sugar over the dough. fill with the berries, adding the pieces of butter and sprinkling with the granulated sugar mixed with the cornsarch. Wet the rim of the bottom crust and place the top pastry over it, pressing down to seal. Trim away the excess. With the handle of a dinner knife, make a decorative edge and then cut a few slits in the center to allow steam to escape. Brush the thop with a thick brush of cream and sprinkle on the remaining crused cube sugar. Place in a the preheated oven, shut the door, and reduce the heat to 350 degress. Bake for 45 minutes. Remove from the oven and set on a rack to cool slightly before serving. Serve with a dollop of Vanilla-Flavored Whipped Cream on top.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

Comments