by Toni Tipton-Martin | May 5, 2010 | Kitchen Tales

Spending the week preparing for my talk on Southern culinary traditions at the Austin Museum of Art this week led me to a comparison of iconic dishes in cookbooks written by black and white authors. The difference? Not much. Not that I was surprised. For years Southern food expert and cooking teacher Nathalie Dupree and I pondered the art and soul of Southern cooking. Our judicious conversations involved unresolved exchanges over thorny topics like boundaries and ownership — a classic study in “my dog’s bigger than your dog.”

If we were having that conversation today it would be muddied by African American authors coming to print with topics that don’t conform to the putative soul food paradigm. Add to that the sheer number of books written about the Southern food “experience” and its no wonder the gap between black and white culinary experiences has narrowed. Finally.

Things weren’t always this way. Southern food is perhaps America’s earliest example of “fusion” cooking, influenced by the rainbow of French, Spanish, West Indian, Dutch, German, Chinese and African traditions that seasoned its pots. It is comprised of iconic dishes such as crisp fried chicken, delicate biscuits, crusty cornbread, barbecue, Hoppin’ John, greens and grits. And, it was born in poverty. The cultural quagmire ensued when cooks, both white and black, tried to shed this humble image.

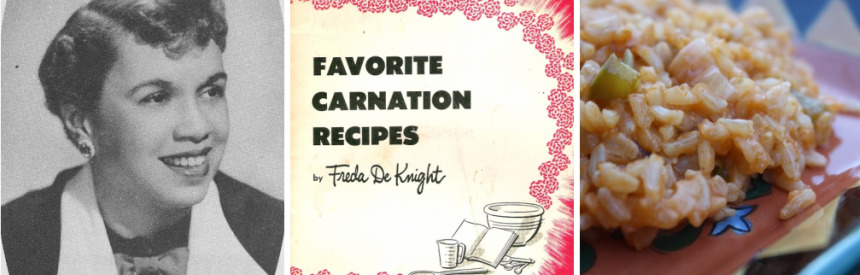

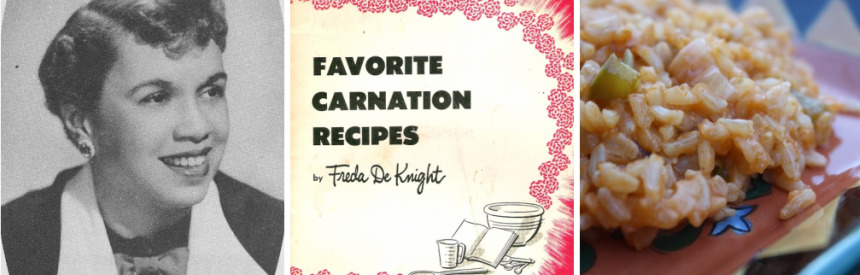

One of the first women to advocate for African American culinary dignity and ownership was Freda De Knight. She is my hero.

As a recipe developer for food manufacturers, and food editor for Ebony Magazine, De Knight understood the work of the kitchen, and she was familiar with the publishing scene when she undertook the first retelling of black cooks’ lives from a culinary point of view in her 1948 recipe book, A Date with a Dish. (Date was revised and reprinted as The Ebony Cookbook, in 1962. Several years later, the Carnation Company tapped De Knight to pen a booklet of “Favorite Carnation Recipes” using evaporated milk.)

With the help of a device she called the Little Brown Chef, De Knight asserted great confidence in her ancestors’ creative accomplishments, their “natural ingenuity” and love of good food. She elevated the tricks of “old school cookery” in a way no one before had tried – beyond the limits of poverty food. She wrote:

It is a fallacy, long disproved, that Negro cooks, chefs, caterers and homemakers can adapt themselves only to the standard Southern dishes, such as fried chicken, greens, corn pone and hot breads. Like other Americans living in various sections of the country they have naturally shown a desire to become versatile in the preparation of any dish, whether it is Spanish, Italian, French, Balinese or East Indian in origin.

De Knight obviously recognized that a well-organized compilation of explicit recipes would have staying power and attract a wide audience. In more than 400 pages, she offered something new– entirely new at least as far as black cookery was concerned – to the cookbook buying public: The secrets of proficient African American cooks, in a “non-regional cook book that contained recipes, menus, and cooking hints from and by Negroes all over America.”

De Knight built a strong case for the versatility and adeptness of African American cooks by expanding classic cookbook sections on household hints and cooking tips. She suggested colorful vegetable plate combinations for holidays and spring menus. Gave clear and concise directions for humane preparation of live lobsters. Recommended methods of preparing and serving new food varieties. And, she infused her technical instructions with entertaining vignettes, which she collected while traveling from South Carolina to Michigan to conduct interviews and gather recipes from black chefs, renowned caterers, celebrities, and everyday home cooks. It is a cruel irony that the delightful tales in her “Collectors’ Corner” galvanize the mission to honor invisible African American expertise, but they were omitted from later editions. If you can get your hands on the 1948 edition, snap it up. Meanwhile, enjoy this little sample:

My father died when I was two and because my mother was a traveling nurse, I was sent to live with the Paul Scotts in Mitchell, South Dakota. The Scotts were famous at that time as being the finest caterers in the middle west and among the finest in the country. They had their own farm and raised most of their own products. They raised chickens, made their dairy products, did most of their canning and had the traditional country smokehouse for their own meats. the made the first Potato Chips for retail sale in that part of the country.

“The Scotts were the inspiration for my early cooking aspirations which gave me every opportunity to absorb all of their fine recipes and rudiments of cooking, preparing food, and catering. Although Mama Scott’s education was limited, she could measure and estimate to perfection without any modern aids, and her sense of taste, her ability to create was phenomenal…

Because of De Knight we can see how an old school cook might have been unable to tell you whether three pinches of salt was equivalent to a half-teaspoon, but she knew whether it was enough to season your cornbread. As a result, she imparted more tips, more insight, and more wisdom at a time when modern kitchen conveniences and TV dinners minimized a housewife’s encounters with food, and threatened to turn mealtime into a brief, impersonal experience. De Knight’s self-assured truisms uplifted cooks:

Cooking is not a problem,” she said. “It’s just knowing how and mastering the little tricks of the profession with ‘thought’.

Who is your kitchen hero?

In Her Kitchen

Freda’s Spanish Rice

Ingredients

- 3 tablespoons butter, bacon drippings or oil

- 1/2 cup chopped onion

- 1/3 cup chopped green pepper

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 tablespoon chopped celery

- 1 cup whole grain brown rice

- 3 cups boiling water

- 1/3 cup tomato sauce or 3 tablespoons tomato paste

- 1 teaspoon salt

Instructions

- Heat oil in a heavy skillet. Saute onion, pepper, garlic and celery until tender. Do not brown. Stir in rice, stirring until well mixed and rice is lightly browned. Add water, tomato sauce and salt. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat and cook over very low heat, covered, until rice is light and fluffy. Stir lightly with a fork before serving. Grains should be whole and firm.

Number of servings: 6

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 28, 2010 | Community Cooks

What do you do to become a better cook? Consult an expert, of course. That is exactly what readers did in 1930’s Maryland when The Baltimore Sun published Aunt Priscilla’s Recipes, a regular recipe column of conversational culinary advice.

The writings followed a common style for the time. Every day, Aunt Priscilla answered reader requests. Every day a recipe followed a brief statement of culinary wisdom with dishes that were sweet and savory, simple and complex. Some days, she offered ideas for variations; other days she shared make-ahead secrets. But always she spoke in pernicious slave dialect. A Jemima-like illustration accompanied her words.

“I’se bery glad to gib you de crab recipes Miss Katie, speshully as serbil mo’ ladies done ast fo’ de same. Try yo’ crab cakes dis way.”

Odd communication for a black woman so intelligent that a major metropolitan newspaper featured her recipes, right? It becomes even more so as the truth about Aunt Priscilla unfolds.

Discovering Aunt Priscilla several years ago was the highlight of my search for evidence of real black cooks in the archives of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive at the William L. Clements Library on the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor. It was there that I encountered her perky little cookbook, Aunt Priscilla in the Kitchen, A collection of winter-time recipes, seasonable menus and suggestions for afternoon teas and special holiday parties, authored “By Aunt Priscilla, herself.” The tidy collection represented a stunning departure from the publishing traditions of previous generations, ushering in a new way to cloak black women’s kitchen skill. (Some time later I added a couple dozen Aunt Priscilla newspaper clippings to my collection.)

The years following the publication of the influential The Boston Cooking School Cookbook, by Fannie Merritt Farmer, were chaotic for cooks. In the North, the domestic scientists classified and codified cooking, while their contemporaries in the South elevated their culinary proficiency by lifting up local specialties, and the pleasures of regional soil — the taste of terroir as we know it today. The Southern belles also published collections comprised of recipes accumulated from “our famed cooks.”

This struggle to define and defend southern regional cooking paradoxically turned the spotlight on black culinary prowess, as prolific Southern authors got caught up in the Antebellum nostalgia sweeping the South. In the introduction to her comprehensive 1927 compilation, Mammy’s Cook Book, Katherin Bell, provides a snapshot of the formula.

“With the dying out of the black mammies of the South, much of the good and beautiful has gone out of life, and in this little volume I have sought to preserve the memory and the culinary lore of my Mammy, Sallie Miller, who in her day was a famous cook…”

Over on the Atlantic Coast, Harriet Ross Colquitt affirmed the black cook’s talent when she published the Savannah Cook Book in 1933.

“We have had so many requests for receipts for rice dishes, and for shrimp and crab concoctions which are particular to our locality, that I have concentrated on those indigenous to our soil…begging them from housekeepers, and trying to tack our elusive cooks down to some definite idea of what goes into the making of the good dishes they turn out.”

Eleanor Purcell, the white secretary of one of The Sun’s most distinguished writers Frank Kent also was among the compilers extracting the coveted specialities of “colored cooks,” but she took a different tack. It was she who posed as the spurious Aunt Priscilla, and the one who answered reader requests for everything from divinity to chili con carni, according to Alice Furlaud. (Furlaud explains how she came to own a copy of Aunt Priscilla’s Cookbook, and how she plied the true identity of Aunt Priscilla from Baltimore friends in a 2008 NPR story.)

But what does it matter? A lot, I think.

In their complete exasperation from trying to prove the value of their cuisine, Southern housewives documented black culinary skill that has been virtually ignored in modern history.

“Most of these recipes were Mammy’s,” Katharin Bell explains. That means that Sallie Miller was competent in more than 300 recipes, many of which are still Southern standards today. The women of Colquitt’s Savannah community demonstrated excellence as entrepreneurs. “The majority of Savannah housekeepers prefer to buy their sea foods from the negro hucksters who…peddle their wares from door to door,” Colquitt writes. And, mythical Aunt Priscilla was the voice and the face of the first African American newspaper food columnist.

Duncan Hines summarized it this way:

“Many Southern ladies had Negro cooks to help them; and just how much we owe to their skill I have no way of knowing except that almost all of the finest Southern dishes are of their creating or at least bear their special touch and everyone who loves good cookery should thank them from the bottom of their heart.”

*

The following recipe was taken from one of Aunt Priscilla’s many newspaper columns.

Aunt Priscilla’s Crab Cakes

To 1 poun’ ob crab meat take 1/2 a small lofe ob bread, 2/3 ob a cup ob milk (6 tablespoons), 2 eggs, 3/4 ob a teaspoon ob musta’d (dry), 1 tablespoon ob Wooster saus, salt an’ pepper to sute yo’ tas’e an’ a dash ob kyan. Crumble de bread an’ poe ober it de milk, lettin’ it set while you fixes de res’ ob de ‘gred’ents. Beat de eggs lite wid de sesinin’, stir in de crab meat an’ mix all togeder wid de bread. Hab yo’ skillet well greased an’ hot. Make out de cakes an’lay on’y as many as you kin han’le e’sy in yo’ pan at a time. Brown fus on one side, deon on de oder, bein’ keerful not to let ‘em burn.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 20, 2010 | Community Cooks

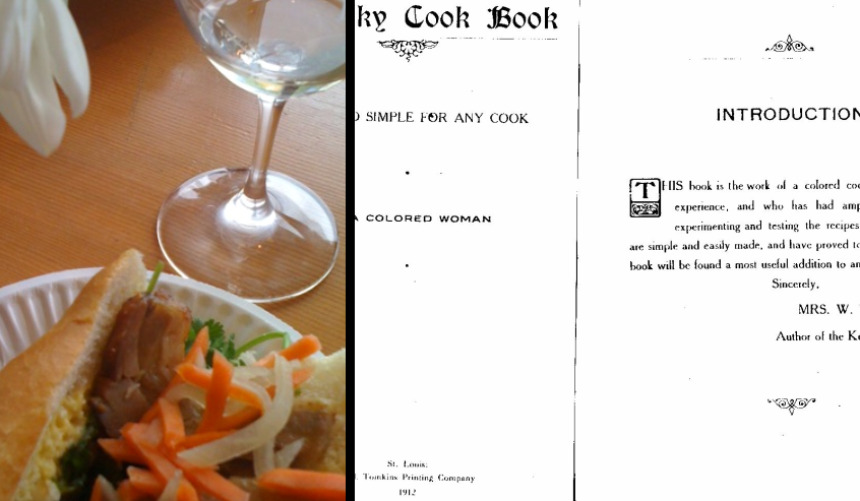

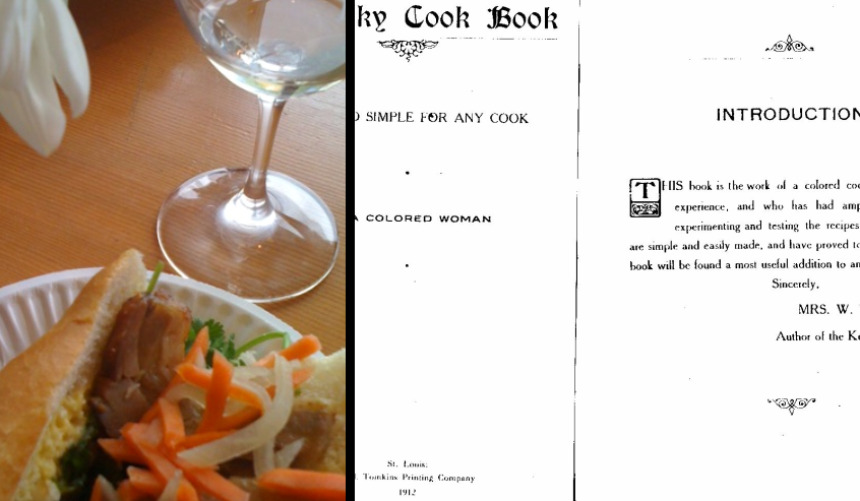

Who is Mrs. W.T. Hayes and why does she matter? The question has baffled me since my friend and Southern sage John Egerton generously gave me her mysterious little recipe book back in the late 1980’s. Now, finally, an answer.

I was beginning my journey as a curious student of African American culinary history; John was the first luncheon speaker I ever heard publicly credit African American cooks for their contributions to the world of cuisine. At the conclusion of a lavish meal featuring southern grilled quail served over his animated and compelling remarks, I leapt from my seat in the posh ballroom of the Ritz-Carlton Buckhead, and bombarded him with questions. In response to my enthusiasm, John rummaged through his brief case and generously gifted me with Mrs. Hayes’ work: The Kentucky Cook book: Easy and Simple for Any Cook, printed in 1912, authored “By A Colored Woman.”

Today I got a huge thrill thinking about Mrs. Hayes again. I’m attending the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP) conference in Portland, Oregon where, for most of the day, I’ve been on a decadent drinking and eating binge in the Willamette Valley. Three wineries poured incredible pinots from their reserve collections, pairing each one perfectly with pork. But the real treat, the part that made Mrs. Hayes come to mind, was lunch at Nick’s Italian Cafe. The menu celebrated pork and Pinot with elegant and light-styled charcuterie, and amazing wines from Eyrie Vineyards. (I could go on and on just about the 2005 Eyrie Pinot Noir pressed from the original, 40-plus-year-old vines brought to the region by David Lett [aka Papa Pinot], but that is another story.)

The chef fascination with pork belly is not news, but the thing I couldn’t help notice was that pork offal was all over the place, on menus, I mean. From a fabulous spicy Vietnamese Bahn Mi sandwich to a decadent Italian pork trippa (tripe) with soft cooked egg and salsa verde, creative expressions of unwanted pig parts ruled the day. Mrs. Hayes had been one of those imaginative and industrious cooks in her day, too, turning sows ears, tails, hoofs, intestines, and private parts into sustaining and delicious dishes. And fortunately her recipes were collected and recorded not as poverty or cabin food, but as signposts of excellence.

I had to know more about this courageous woman who brazenly flaunted her race before the book-buying public, so I took a research trip — coincidentally funded by a grant from the IACP — to the Historical Society in Frankfort, Ky., to look for clues. What I discovered about Mrs. Hayes was better than the discovery of the book itself.

The Kentucky Cook Book was published in St. Louis by the J.H. Tomkins Printing Company, a job printer, which occupied a small room on one floor of a commercial building in Missouri. It contained 45 pages of short recipes composed in the narrative style, and for the most part followed the paragraph form of Mrs. Reese Lillard’s Tennessee Cookbook, which came to print the same year. Strangely, only a fraction of Kentucky’s 250 dishes were characteristically Kentuckian. Just two hint at African American tradition – macaroni croquettes and okra salad (unless you count fried chicken, but I have covered that in earlier posts).

The Library of Congress says the registered author of the Kentucky Cook Bookwas Mrs. Emma (Allen) Hayes, not the Mrs. W.T. Hayes identified in the Introduction. A search of the Kentucky Death Index turned up five women named Emma Hayes, and one man, a W.T. Hayes. Of the women who were the appropriate age, one Emma was married to W.T. Hayes. W.T. must have been a nickname for Allen, I thought; mystery solved. Well, that is until further investigation revealed that this Mr. And Mrs. Hayes were not colored. They were white.

And I’m not sure it matters. Here’s why.

In a class of American cooks struggling for identity, Emma Hayes laid a foundation for future black cookbook authors, proving that great cooks can and did have vast repertoires that included but were not limited to foods from the fifth quarter. And, even if she was the white mistress who simply helped bring a black woman’s talent to the page, she joins the tiny band of supporters who boldly fought against the plantation cook stereotype by recording recipes and giving them credit for their mastery.

Together these women crossed a dangerous social bridge when they rescued African American cooks from prejudiced interpretations of their character. And that truth leads to an appreciation for the rich culinary legacy created when – not one, but two – cultures came together over bubbling kettles of greens and skillets of pone to evolve an historically important and still beloved cuisine.

Salut!

*

Here is a recipe from the Kentucky Cook Book that hints at the tripe and egg nestled in a satiny tomato sauce we enjoyed today on wine tour. I wonder what wine Mrs. Hayes would recommend?

STEWED KIDNEY WITH TOMATO

After soaking a beef kidney in salt water over night, stew until tender and until little water is left in the kettle. Cut the kidney into small pieces and thicken with flour the water in which it was cooked. Add a tablespoon of butter and the kidney. Serve with boiled tomato and mushroom sauce on toast.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 14, 2010 | Uncategorized

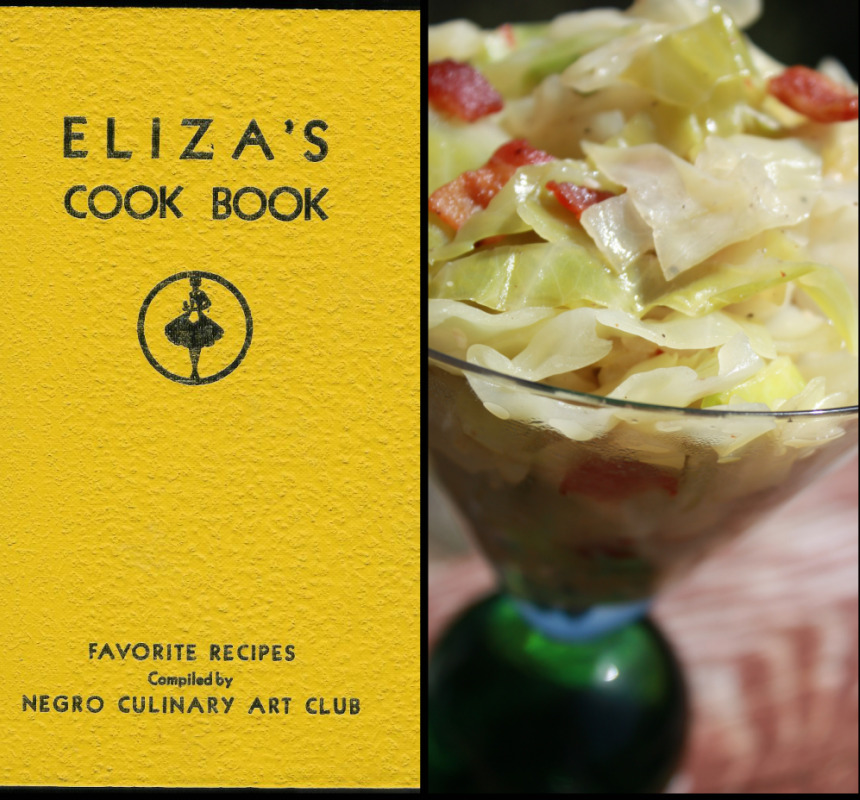

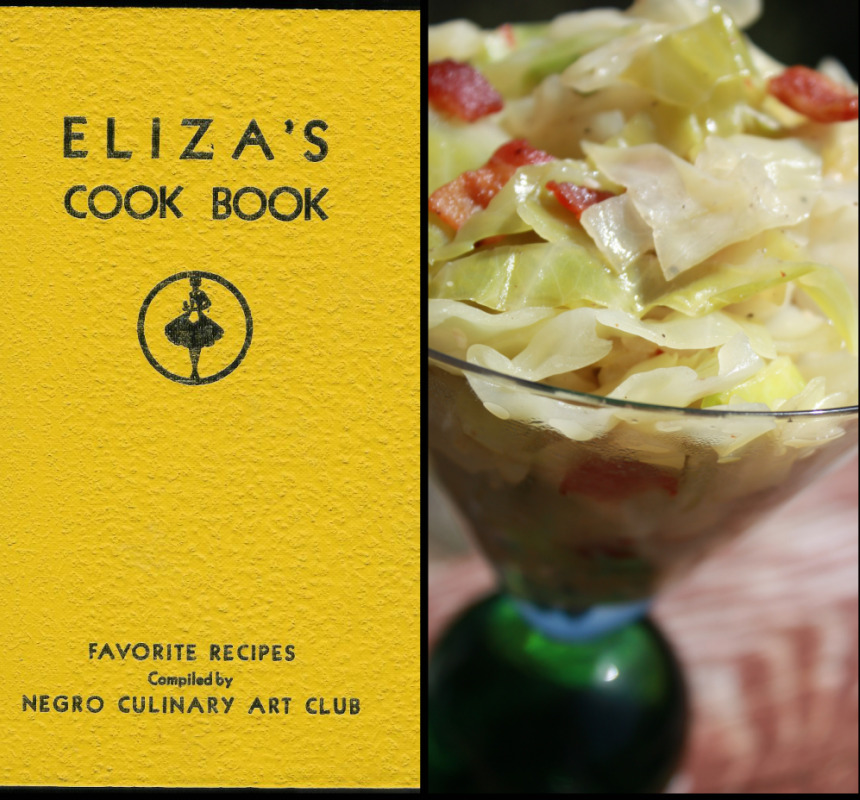

I had already imagined the delicacies and grace that would be rendered by Eliza’s Cook Book: Favorite Recipes Compiled by Negro Culinary Art Club of Los Angeles long before I ever bid my way to a rare and highly-coveted copy. I can tell you this sophisticated gem of some 100 pages is a miraculous find and a lovely example of African American flair in the ever-present asymmetry of the Jemima cliché. It shows that there was another side to black female cooks – a side with class.

Eliza was organized by Beatrice Hightower Cates and published at a time when national pursuits – from board games and radio to mystery novels by Agatha Christie – helped Americans escape the rigors of Depression-era living, while field writers for the Federal Writer’s Project, a part of the Works Progress Administration, recorded the life stories and oral histories of former slaves.

Amidst all the resources women had for scientific cooking and healthful meal planning the members of the Culinary Art Club obviously noticed a void. Cooking is indeed a science, but it is also an art – one that requires special attention, whether the cook is occupied with a simple method like brewing coffee or a more elaborate project, such as making a velvety sauce. Cates and the members of her club clearly knew the pleasures of fine cooking and took pride in their extensive catalog of “ladies’ luncheon” and light dinner dishes.

The recipes were decidedly upscale. To acknowledge the cultural tradition of hospitality and enrichment, Eliza was “Dedicated to the mothers of the members of the Culinary Art Club,” women who probably descended from slaves. And yet, I couldn’t help but notice once again how few historically Southern recipes are here. At first glance this practice seems disingenuous, but I don’t think it is as simple as that.

Eliza’s liberated cooks probably had unlimited access to finer cuts of meat and better quality vegetables, enabling them to extend their repertoire beyond biscuits, cornbreads, and croquettes. At least that’s what is reflected in the recipes they selected for their cookbook. Dishes range from assorted canapes, to creamy bisques and soups, saucy fish and lobster concoctions, all manner of meat and game (including steaks, roasts, and casseroles), vegetable sides from A to Z, and dozens of rich breads and sweets.

Neither cabin methodology nor the haze of hard labor that hovered over black kitchens appears to restrict their creativity. They didn’t let the yolk of tough economic times, lack of information, or even minimal cooking skills stifle them. Nor should we.

Times like these call for a return to the kitchen, and these women prove to us that trip doesn’t have to be laborious or difficult. Just get out a simple, but classic recipe and practice, practice, practice. When it’s time to serve your masterpiece, remember two the things the Culinary Art Club teach us: Exceptional cooks aren’t born, they are made; and attitude is everything.

Even a homespun recipe like smothered cabbage can be made extra special, as Cates recommends. She simply layers shredded cabbage in a casserole with tomatoes, bacon, onions and green pepper, then crowns the dish with a dusting of Parmesan cheese before baking.

This basic cabbage saute should help get your imagination started.

In Her Kitchen

Sauteed Cabbage with Bacon

Ingredients

- 6 slices bacon, cut into pieces

- 1 medium onion, diced

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 small head cabbage, thinly-sliced

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon black pepper

Instructions

- Saute bacon in a hot skillet with a tight-fitting lid, until almost done. Add onion and cook until onion is translucent. Stir in garlic and cabbage and cook 3 to 5 minutes, stirring occasionally to prevent sticking. Cover skillet and reduce heat to low. Steam cabbage to desired doneness, 15 minutes for tender-crisp, 30 minutes for completely wilted. Season with salt and pepper before serving.

Number of servings: 6

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 7, 2010 | Entrepreneurs

With Tiger Woods back in the news this week, my thoughts immediately turned to Fuzzy Zoeller’s yakity yak urging Woods not to “order fried chicken or collard greens…or whatever the hell they serve” at the 1997 Masters golf tournament champions dinner. Zoeller might have been one of golf’s most notable players, but he obviously missed the memo on African American culinary tradition.

For generations, African American cooks living outside of the South have enjoyed confident, creative culinary expression, preferring to be known for their artistry, rather than the narrow outlook that limits the African American cook’s repertoire to the poverty ingredients and methods of plantation cabin cookery.

In 1910, while the domestic scientists were analyzing their food, “draining it of taste and texture, packaging it, and decorating it” to accommodate their shifting emphasis to domestic efficiency, Bertha Turner, a State Superintendent of Domestic Science and private caterer published a remarkable cookbook to preserve black culinary identity.

The Federation Cookbook: A Collection of Tested Recipes Compiled by the Colored Women of the State of California, assembled delicious recipes from the noted cooks living in and around Pasadena. The book exemplified a type of culinary professional who survived blatant discrimination and achieved fame and success.

By coincidence or Divine Order, Turner’s kitchen priorities and caterer’s virtues of uniformity, familiarity, and predictability perfectly aligned with the domestic science movement’s institutional ambitions of standardization and technical know-how. She was also a very good cook, according to the obituary published in a 1938 local newspaper, which also carried this photo of her, dressed elegantly and draped in fur.

She lived prosperously, flourishing in the rich ethnic culture of the Pasadena foothills, and didn’t appear stifled by the Jim Crow ideology strangling her race elsewhere. In fact, her Federation Cookbook set off confidently – perhaps because it epitomized a resolute gathering of out-going, successful women dedicated to social uplift.

Unlike Abby Fisher and Malinda Russell who began their books apologetically, Turner gracefully promised in her Preface to deliver “tested cooking of tried proportions, kindly given by our women.” She boldly suggested that readers purchase the book to thank those “helpful, trusty” women whom she memorialized in every recipe.

“Take it to your friends and neighbors,” she urged. “May it prove a blessing to you.”

Turner probably was obviously a compassionate woman, too. The Federation Cookbook began with a cheerful poem composed by a member of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, to shore up young cooks. She shared more than 200 recipes for simple, as well as elegant cookery, including numerous ways with lettuce, gelatin, and molds – the “dainty” delights popular among domestic goddesses at the time.

Interestingly, the only Southern dishes to survive the trip West with this regal, Kentucky-born patron were croquettes, okra, and cornbread.

Does that answer your question about what we serve, Mr. Zoeller?

*

In Bertha Turner’s day, homemade salad dressings, including mayonnaise were evidence of a cook’s proficiency. The mix is simple: eggs, good quality oil, vinegar or lemon juice, and salt and pepper to taste. With today’s rush through the kitchen, you can achieve potato salad with the same creamy results using commercial mayo and a splash of prepared mustard.

In Her Kitchen

Potato Salad

Ingredients

- 4 slices bacon

- 8 new potatoes

- 5 hard-boiled eggs, peeled and coarsely chopped

- 3 green onions, sliced

- 2 stalks celery, diced

- 1/4 cup sweet pickle relish

- 1/2 cup mayonnaise

- 1 tablespoon mustard

- Salt, pepper

- Paprika

Instructions

- Cook bacon in a hot skillet over medium heat until crisp. Cool and crumble. Set aside. Scrub the potatoes and boil in their jackets until just done. Cool, peel and dice. Place in a large bowl with eggs, onions, celery, and pickle relish. Stir in mayonnaise and mustard, and season to taste with salt and pepper. Sprinkle with paprika before serving.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

Comments