by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 6, 2011 | Entrepreneurs

It seems hard to believe that nine months have whizzed by without even a peep from me and the women of the Jemima code. Please forgive us; we’ve been a little busy.

Just this week, we traveled back and forth between Austin and Houston several times, first to introduce a new cook at Prairie View A & M University’s Cooperative Extension annual State Conference and Awards Banquet, then, to install an exhibit at Project Row Houses, where the Blue Grass cooks will be on view for the next two months. In between, there were multiple event planning meetings and nursing a kid recovering from ACL surgery.

Oh my goodness.

Everyone warned me when I started this blog project over a year ago not to put myself under pressure to be brilliant or witty on demand, like pay-per-view. But I am a journalist, for Heaven’s sake! I require a deadline to stay on task. Besides, as far as Jemima tales are concerned, I could go on and on and on.

So what a surprise that after my trip to the White House for Chefs Move, I didn’t go on at all. Instead, I stopped researching new women and accepted way too many opportunities to serve the community — as chair of the host city committee for the 33rd annual conference of the International Association of Culinary Professionals, and vice president for Foodways Texas, a new organization modeled after Southern Foodways — all while teaching kids to like the taste of kohlrabi everyday after school. The University of Texas honored the nonprofit cooking organization I founded with a service award for all of those healthy kiddy cooking classes, but my heart beat louder and louder for more Jemima tales.

What would you do? What Jemima would do, of course.

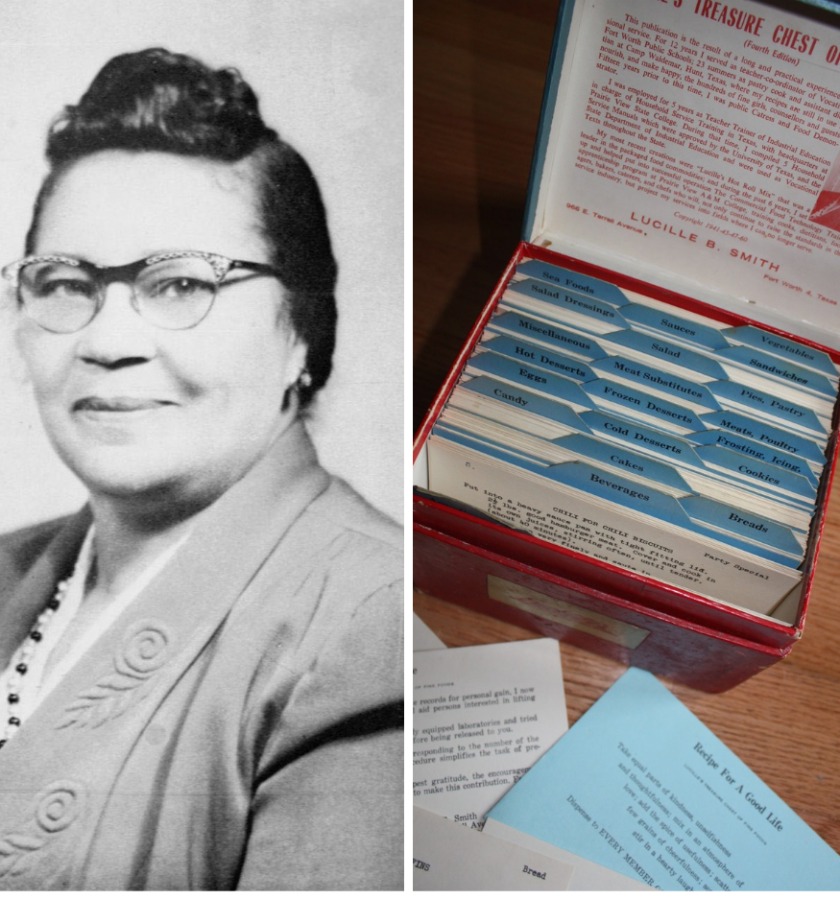

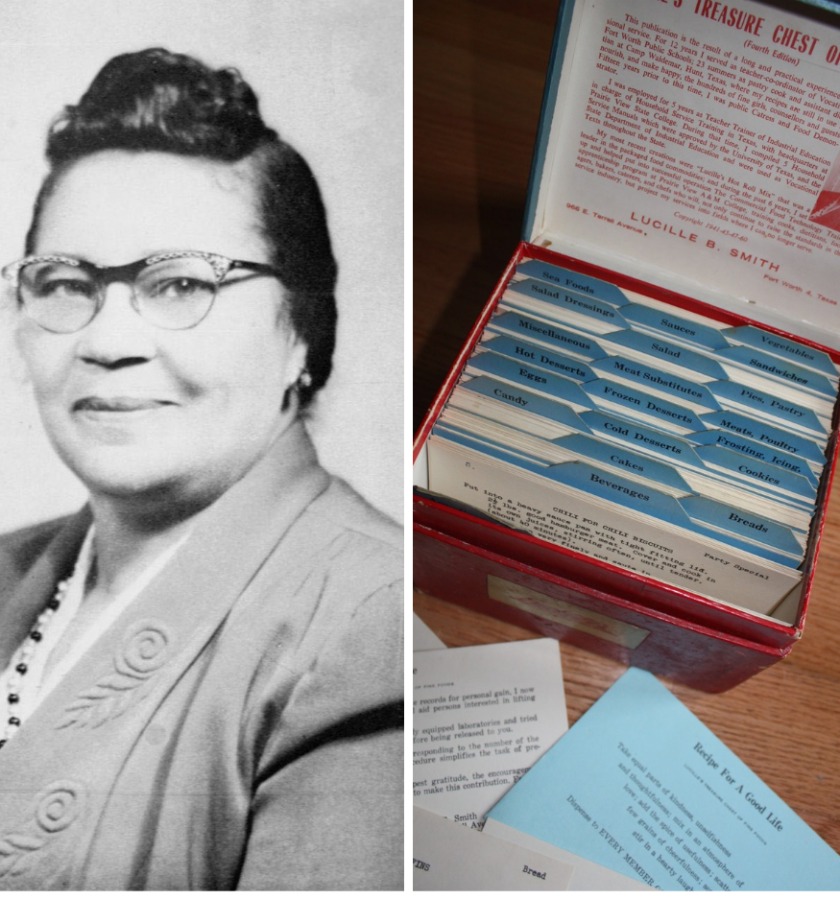

I started sharing “my girls” with live audiences too, presenting Jemima as a role model at meetings of the Culinary Historians of Southern California, the National Forum for Black Public Administrators, and Slow Food Austin. I also told a grateful Prairie View audience about an inspirational woman with an inventory of professional culinary accomplishments and community work so long the city of Ft. Worth honored her with a day named just for her. Her name was Lucille Bishop Smith.

This was a good week for Lucille’s whispered wisdom.

For me, this Tarrant County native upheld the African American cook’s nurturing character while teaching the value of discipline, confidence, and creative thinking during difficult times. Not coincidentally, her profile demonstrated numerous ways that organizational, technical, and managerial skills can be added to the profile of American black cooks.

Lucille lived productively, establishing herself as a respected professional with a local and state reputation during the Great Depression, and publishing more than 200 delicious recipes for simple, as well as elegant cookery, in Lucille’s Treasure Chest of Fine Foods. She raised funds for community service projects, fought to raise standards in slums, developed culinary vocational programs in Ft. Worth and at Prairie View, was responsible for the first extension workers being employed in Tarrant County, brought the first packaged Hot Roll Mix to market, conducted Itinerant Teacher Training Classes, developed Prairie View’s Commercial Cooking and Baking Department, compiled five manuals for the State Dept. of Industrial Education, and was foods editor of Sepia Magazine. And all of that is just part of her resume. Her bio concludes:

“She represents a faithful wife, a devoted mother; a devout Christian, a character builder, a successful business woman, a pioneer in education ventures and a dedicated servant of people.”

Lucille’s Treasure Chest epitomized her life’s work to empower others by using food as a tool to achieve social uplift. In the Preface, she encourages women of the community to follow in her footsteps with this Recipe For A Good Life:

Take equal parts of kindness, unselfishness and thoughfullness;

mix in an atmosphere of love;

add the spice of usefulness;

scatter a few grains of cheerfulness;

season with smiles;

stir in a hearty laugh, and

Dispense to EVERY MEMBER OF YOUR FAMILY

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jun 16, 2010 | Uncategorized

I was busy digging around in American history looking for evidence that black cooks had earned the title of chef when the invitation to the White House arrived in my email. For years, I have been trying to clarify the fuzzy characteristics that epitomize chefdom in order to understand the role black cooks played in creating American cuisine. The First Lady turned that inquiry into a personal awakening.

You may remember from my last post that Michelle Obama called upon chefs from around the country to join her on the South Lawn as she introduced a new initiative in her Let’s Move campaign to help solve the childhood obesity epidemic in a generation. The invitation explained that the Chefs Move to Schools program would pair chefs with schools in their communities to teach kids about food, nutrition, and cooking in a fun and engaging way. And, it required those of us already working with schools to complete a questionnaire and chef’s profile.

The nonprofit organization I founded two years ago to teach cooking, heritage, and nutrition to underprivileged kids definitely qualified for the program, but me, a chef? I might be an excellent cook, but the difference between that and the artistry of a master chef is like comparing Derek Fisher to Kobe Bryant (I’m from Los Angeles; what do you expect?).

Eventually however, qualified sources convinced me that the women of The Jemima Code deserve chefdom. Maybe I do, too. The etymology of the noun chef is French, short for chef de cuisine, says Merriam-Webster. The term dates to 1840 and is defined simply as “a skilled cook who manages the kitchen.” In the 1977 edition of The New Larousse Gastronomique, the internationally-known culinary bible, the chef de cuisine is known as a “director responsible for a cooking team.” Chefdom, I reasoned, does not just mean one who is educated in classic technique at a well-equipped culinary academy — even though that is exactly the interpretation proclaimed by those with the synoptic view that “chefs are professionally trained, cooks are not.”

I filed the documents, packed my chefs whites, and got on the plane to Washington D.C.

The air was hot and sticky on the morning of June 4, filled as much with moisture as excitement, as I stood in line on East Executive Avenue NW waiting to clear the first secret service checkpoint. Friends and I gabbed nervously about work, pausing every now and then to marvel at the mist of nearly 700 chefs, and to take pride in the diversity of the crowd. Once through the second security stop, we received paper chefs hats with a Let’s Move message from First Lady Michelle Obama printed on the rim:

“We are going to need everyone’s time and talent to solve the childhood obesity epidemic and I am calling on our Nation’s chefs to get involved by adopting a school…you have tremendous power as leaders on this issue because of your deep knowledge of food and nutrition and your ability to deliver these messages in a fun and delicious way…”

Next it was off to the South Lawn. The mood was bright with exhilaration and we embraced one another while taking pictures as if we were little children on their first trip to a Disney theme park. Chefs posed everywhere: In front of the White House; beside the Ellipse; at the podium; between the collards and the rhubarb in the vegetable garden. After about an hour we wound our way through the gorgeous grounds, lured to the hilltop by the sound of a small band. We took turns alternating between saving seats and cooling off under the gallery of shade trees. Then an announcer asked us to be seated.

The anticipation was as high and our togues were drenched. In time, the chatter quieted to a hush and we sat on the edge of our seats watching and waiting for a sign of life at the door to the lower level of the White House. And then, she was there. Close enough to touch. Beautiful and poised. Articulate. Mrs. Obama echoed the remarks made earlier in the day at the Share Our Strength breakfast, encouraging the crowd, among other things, to be patient and considerate of cafeteria food service professionals — not just talented and skilled — when we set out to teach cooking and nutrition in schools.

The program concluded when the First Lady retreated to the garden to harvest vegetables with a few children and some of the food industry’s elite, including Marcus Samuelsson, Tom Colicchio, Cat Cora and Rachel Ray. The rest of the group remained in a glow of amazement, inspired by this executive expression of support, energized for the challenges that lay ahead.

And I contemplated a debt owed to generations of African American chefs who paved the way for me with little recognition — women who might have been asked to labor here, but never would have been treated to such an honor. I lingered a few minutes more in this opportunity of a lifetime, then peeled off my sweaty chefs coat — the one with The Jemima Code embroidered near my heart — and settled into my new role.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jun 2, 2010 | Domestics

This Friday when Michelle Obama welcomes top chefs and food professionals from around the globe to the White House to introduce the latest ingredient in her recipe for changing the food habits of America’s kids, the women of The Jemima Code and I will be among the privileged in chefs coats stirring the pot.

Through a partnership with food professionals’ organizations such as Share Our Strength, the National Restaurant Association, the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP), Women Chefs and Restaurateurs (WCR), and Les Dames d’Escoffier, chefs and cooking teachers will exchange ideas about increasing nutrition awareness as Mrs. Obama launches the Chefs Move to Schools program.

Her idea is simple really. Because chefs have a unique ability to deliver health messages in fun and creative ways, Chefs Move to Schools was created to challenge culinary experts to adopt a school and work with teachers, parents, school nutrition professionals and administrators to help educate kids about food and nutrition, according to the website, www.letsmove.gov.

Chefs Move will be operated by the Agriculture Department and will pair chefs with interested schools in their communities so they can create healthy meals while teaching young people about nutrition and making balanced and healthy choices. The White House assembly will include culinarians who want to join the campaign, as well as those who are already empowering children toward healthy, productive futures. Like me.

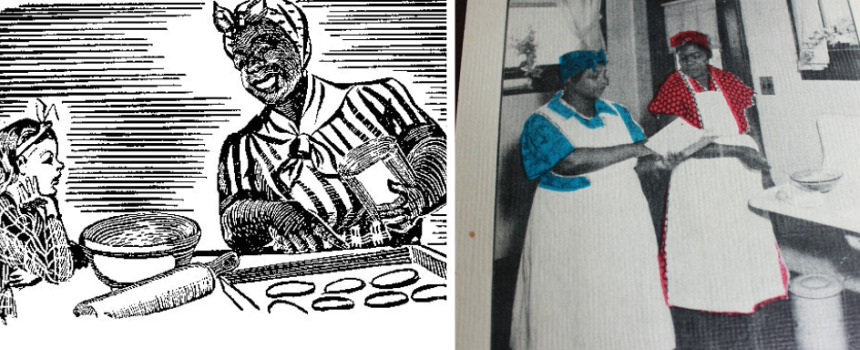

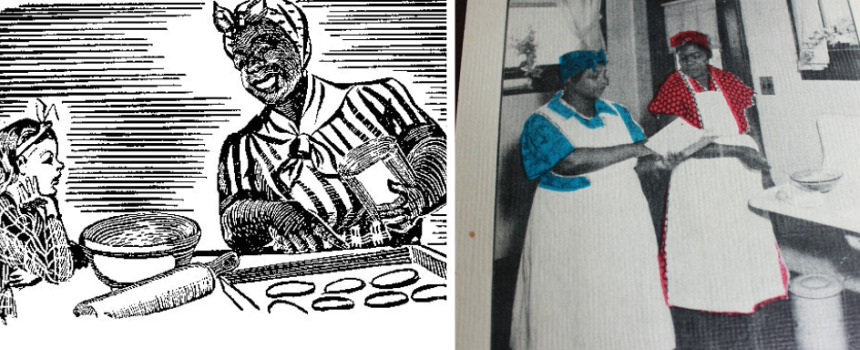

When I the built The SANDE Youth Project in 2008 after 25 years of using written words to teach readers about cooking and nutrition, I returned to the same foundation of oral tradition that my ancestors used to impart proficiency, morals, self-esteem and respect for the community to their children and the children of their employers. This illustration from Marion Flexner’s 1941 cookbook, Dixie Dishes, was published to keep black women in their place by contrasting the child-like housewife to a massive cook towering above. For me it simply proves that African American cooks have always been skilled culinary educators, whether credited for their knowledge or not. And that truth informs both my hands-on and written work.

Both SANDE and the women of The Jemima Code communicate important life skills and the tenets of healthy eating while making tasty recipes. Both teach by including the student in the process. And, both rely on age-old wisdom. The difference is that elementary school-age kids at SANDE learn from high school and college students.

The pilot program expands the Healthy Families Initiative at the University of Texas Elementary School through a community partnership with UT’s Division of Diversity and Community Engagement. The kaleidoscope of student-led gardening, heritage, and nutritious-cooking activities nourish and empower underprivileged families the way that Mrs. Obama’s Let’s Move campaign returns responsibility for the health of children to the community. It is a unique approach, also instilling 10 Core Values in the areas of Spirit, Attitude, Nutrition, Deeds, and Emotions (SANDE).

At SANDE, we hope to give kids a head start on healthy futures, at the kitchen table, one meal at a time. Students follow their food from seed to plate. They learn the importance of kitchen organization and safety. Develop the taste for food that is fresh and preservative- and additive-free. Discover that it is the raw egg that makes their favorite cookie dough unsafe to eat before baking. And, they gain literacy from reading recipes and writing their own cookbook while manipulating fractions and solving questions of chemistry. The kids are not, however, learning how to cook diet food.

After two hours pounding chicken breasts, grinding and toasting their own homemade bread crumbs, and shredding Parmesan cheese for chicken Parmesan, tasting a dozen green leaf varieties before assembling salad, and churning their own homemade ice cream, a group of giddy 10-year-olds hurries excitedly to set the table for lunch. One of the boys who came to class thinking that cooking was girly described the SANDE experience best when he stated:

“Man, I can’t believe I made this.”

A few bites later, he added, “I can’t believe this tastes so good.”

When lunch was over, he exclaimed: “I can’t believe I made this and that it tastes so good!”

Now that is what I’m talking about.

As encouragement to keep them cooking, I shared this tidbit from Aunt Julia and Aunt Leola, authors of Aunt Julia’s Cookbook, the Standard Oil Company of Pennsylvania’s 24-page collection of simple Carolina Low-Country recipes. The message seems especially fitting today.

“For Happy Eating Use These Recipes.”

by Toni Tipton-Martin | May 19, 2010 | Domestics

I didn’t mean to make anyone cry. Quite the contrary. I write thejemimacode to honor invisible women and to celebrate — as in party over here! But recently, more followers of this space are sharing intimate stories off-line of the women whose cooking made them feel special. Now, however, thinking about how unfairly the women were treated makes them terribly sad. Reconciliation can do that.

So, I’m here to cheer you up with news that after the hurt comes the heal, at least that is what we experienced following difficult dialogue at gatherings of the Southern Foodways Alliance. I also want to share the uplifting story of two women who came together to preserve the work of one of those obscure cooks in Rebecca’s Cookbook.

In 1942 while the world was at war, Rebecca West was traveling the country with her “lady” amassing a treasure-trove of receipts and recording her escapades in the local newspaper. That “lady,” known only by the initials E.P. helped West record dozens of dishes, from from terrapin to pate de fois gras, as well as childhood recollections of her visits to South Carolina and miscellaneous ruminations about the Bahamas.

Thankfully, E.P. did not resort to the demeaning Jemima stereotype when she transcribed West’s thoughts and recipes. Yes, West speaks in the broken English that is evidence of a rural upbringing, but she is not portrayed by the maliciously exaggerated speech we’ve seen in recent posts. No elitism here either. E.P. obviously respected West’s knowledge and talent, making no claims to her recipes and stating in a brief editor’s note that “Rebecca is so noted for her terrapin, that it is only right for terrapin to have a separate section all it’s own in her cook book.”

West also tells us a bit about their cozy relationship in numerous references to their experiences together in the kitchen. As the introduction to the Fish section, which features examples of modern cuisine such as red snapper fillets sauteed in olive oil, herbs and shallots, then braised in a tomato cream sauce; stuffed baked black bass; sauteed sea scallops; and scalloped oysters, West offers the following amusing tale.

“One night when my lady was out to dinner the butler came runnin downstairs all out of breath. He said, “The lady said she had the best fish tonight at dinner that she ever had an she wants you to try to fix somethin like it.” I says, “Now wait a minute, wait a minute. How does she know it was fish she was eatin?”

He says, “She said she could only see the tail of the fish stickin up out of a cream sauce an she don know what kind of fish it was, but it was good. You better figure out what it was, Rebecca.”

“So I got to figurin…I know the lady who does the cookin where my lady was havin dinner, so I says to the butler, “Joe you skip over there an ask her will she oblige me with the recipe for the little fish with cream sauce they had for dinner tonight…Just as I expected, the dish wasn’t made of little fish at all. It was ham. My lady was so surprised when I told her. She says, “That’s what comes of dinin by candlelight.”

Anyways here’s some receipts which is really fish…”

Precious, isn’t she?

Anyways, after a quick flash in a hot skillet, Rebecca layers red snapper fillets in a baking dish and covers with a cream sauce before baking. We don’t eat much cream at my house so I adapted Rebecca’s snapper to suit my family’s tastes and today’s demand for food that is light, fast and hassle-free. I started with my kids’ favorite way with spinach (lightly sauteed with a little garlic and onion), then used the mix as a bed for rolled and stuffed fillets. Rolling the fish is beautiful and makes dinner seem special. A quick steam, some hot cooked rice, and a healthy dinner is done. Thanks, my ladies.

In Her Kitchen

Red Snapper Roulades with Spinach

- 4 red snapper fillets, skinned and boned

- Salt, pepper

- 1/4 cup prepared spinach dip, about

- 1 tablespoon each olive oil and butter

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 large shallot, minced

- 1 pound fresh baby spinach, rinsed and drained

Instructions

- Season fillets lightly with salt and pepper. Place fillets skinned-side-up on a board. Spread each fillet with 1 tablespoon dip. Roll fillets to enclose dip, beginning with the widest end of the fillet. Secure fish rolls with a wood pick and set aside. Heat oil and butter in a large skillet until sizzling. Add garlic and shallot and saute until tender. Add spinach to the pan and cook about 5 minutes until wilted but still bright green. Place fish rolls on top of spinach. Cook, covered, over medium heat, 10-15 minutes, or until fish is no longer opaque. Remove wood picks before serving.

Note: Do not dry spinach leaves completely. The moisture from rinsing provides the steam that cooks the fish without over cooking the spinach.

Number of servings: 4

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | May 12, 2010 | Domestics

Everyone asks me the same question when I hand out my business cards:

“What did you think of The Help?”

Sheepishly, I admit that I haven’t read the best-selling novel. I can’t.

You should know that my calling card bears the image from this blog on the front, and a 1904 photo of a black cook on the back. That is because the women of thejemimacode are the backdrop of everything I do — from my writing and speaking to the nonprofit organization I’m building in Austin. I’ve spent so many years researching real domestic servants, that it is taking some time for me to warm to the idea of another fictionalized accounting of their lives. I’ll tell you why.

When I began this project I promised never to purchase any of the plantation cookbooks that degraded African American cooks with distorted images and vernacular language. Nor would I collect any of the “black Americana” kitchen collectibles featuring bug-eyed household servants as salt and pepper shakers, and on dish towels, spoon rests and the like. (My ambition is to collect artifacts that improve the image of African American cooks, not destroy it.) Trusted friends tell me that this new novel is fair and pleasant, but I have spent too many nights crying myself to sleep from reading slave narratives at bedtime to bankroll overt racism. I’m not saying The Help is bigotry; I’m just mustering the courage to see for myself.

My anxiety can be traced to the horror I experienced when I finally obtained a copy of Emma Jane’s Souvenir Cook Book And Some Old Virginia Recipes, Collected By Blanche Elbert Moncure, only to discover its encoded sentiments. I optimistically hoped that the shared by-line to this book represented an end to the common practice of recipe books published on behalf of black domestic workers deemed too ignorant to record their own recipes. And, I was pleased that the introduction to this 80-page collection included Jackson’s photo — not a cartoon — with this innocent characterizatization: “a good and faithful servant who has lived in the writer’s family for over 50 years.”

Jackson, a real woman? Yes.

Moncure, her advocate? Probably not.

From here, Moncure went on to tell a fanciful tale about how Jackson came to be known by the name printed as the cutline beneath her portrait: Emma Jane Jackson Beauregard Jefferson Davis Lincoln Christian. She followed the wistful tale of Civil War soldiers and “the little nigger baby” with Emma Jane’s culinary advice to the bride-to-be derisively:

“Well, Miss Sally, I sho‘ gives you all of my complements an‘ good wishes! Fur, when a young lady laike you is, begins to compensate matimony, de very bes‘ path she can take is dat one dat leads straight to de kitchen…But look here! Why is you a comin‘ to me, fur de informity? I aint no cookin‘ teacher! I is jes a plain uneddicated cook-o’man, what can’t even read her own name, much less a ‘ceat book! You have to go to college an‘ ‘tend dose Messy Sciences Classes dese days, to be what you calls a fuss class cook! So don’t come in dis kitchen, effen you wants to be in de fashion…Of cose, I been cookin’ fur a purty long time when you come to think of it…I recon I ought to be able to give you some ‘vice ennyways, what may come in handy — dat is — effen you lissins to it.”

I was not dismayed by the familiar storyline, but did I want it as part of my library? Did I enjoy reading it for entertainment? Not so much. What I did do was manage to distill a few bits of Emma Jane’s culinary wisdom and some of her thoughts about locally-sourced, seasonable foods, the way that the women of my muse prepared nourishing meals from discarded garbage. I’ll paraphrase.

- We eat first with our eyes, so always pay attention to the table, whether it is just a plain pine kitchen table or a shiny mahogany table dressed with fine lace and candles. A floral centerpiece is good for digestion. The sight of it is good for sore eyes.

- Making biscuits is easy, but pay attention! Have that oven hot. And I mean hot before you put those biscuits in there. A cold oven is responsible for more brick “bats” than most people think. The poor bride is blamed for it all, when in fact the oven is more to blame.

- Some folks serve stewed oysters for breakfast down in this part of the country, but try to get them as fresh as you can for they can “kick up Hally-lu-ya” (make you sick) if they are old. Of course, the winter months are the best time of year to get the most flavorful taste. In the summer, they are poor and milky-like.

- Don’t go to the store for your holiday turkey. They aren’t fit to eat. Go to a dependable person who knows his business (know your farmer) and let him pick, slaughter and prepare a plump hen for you. Half your preparation troubles will be over.

Maybe The Help won’t hurt after all.

What were your thoughts after reading it?

In Her Kitchen

Emma Jane’s Buttermilk Biscuits

Ingredients

- 3 cups all-purpose flour

- 1 tablespoon baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 cup lard, cut into pieces and chilled

- 3/4 to 1 cup buttermilk

Instructions

- In a large bowl, whisk together the flour, baking powder, soda and salt. Cut the lard pieces into the flour mixture using two knives or a pastry blender until mixture is crumbly and lard is evenly distributed. Using a fork, stir in the buttermilk, adding just enough to make a slightly sticky dough. The amount may vary because buttermilk is thicker than milk. When dough pulls away from the sides of the bowl, pour out onto a lightly-floured board. Sprinkle with a small amount of flour and knead the dough about 10 times to make a light dough. Do not add too much flour or handle too much. Pat dough into a 1/2-inch thick disc (or use a rolling pin). Cut with a floured biscuit cutter. Place on a shiny baking sheet, about 1/4-inch apart, or in a baking pan just barely touching. Do not re-roll scraps. Gather into one biscuit or scatter the leftover pieces on the pan and serve as a snack. Bake in a preheated 450 degree oven 10 minutes or until light golden brown. Let cool 5 minutes before serving.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

Comments