Did you ever want something so bad it hurt? That’s how I feel about the last four First Edition African American cookbooks remaining on my Jemima Code shopping list. These extremely rare volumes are all that stands between me and a complete re-write of African American culinary history, told in the voices of the people who did the cooking.

But, this is the story of unrequited love.

My collection includes facsimile copies of these vintage works, and thanks to curators at the University of Michigan and Radcliffe University, I have held these precious gems in my hands, close to my heart. I can still remember how it felt to run my fingers over the gilded lettering engraved on the smooth surface of the cloth boards. I got cold chills as I opened the covers, exposed the fragile, yellowing pages, and uncovered hidden treasure.

Published in the years before and after the turn of the twentieth century, the recipe collections are the rarest of the rare. They are valuable to my mission because they reveal the true Knowledge, Skills and Abilities (KSA’s) possessed by black cooks, whether they were former slaves or free people of color.

It should make no difference that my copies are reproductions. But I want originals. The real thing. Badly. There is just something indescribable about owning such important pieces of history.

Last week, two of the books turned up in an online antiquarian bookseller’s catalog while I was driving to my office downtown. It had only been three hours since the announcement, but the most precious of the books — What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Southern Cooking — was already gone by the time I settled in and logged on. I recovered quickly from the shock of finding a volume published in 1881 by a former slave, Abby Fisher, for the low, low price of $4000.

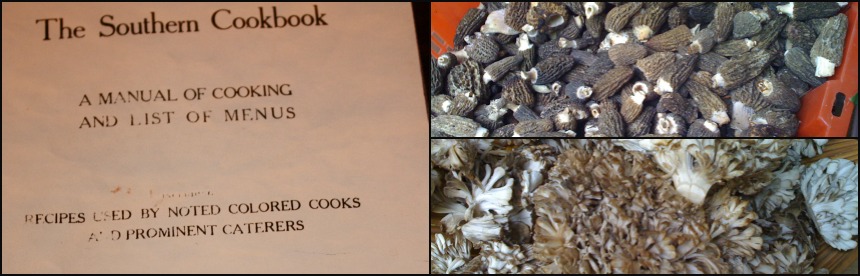

I scrolled to the next entry on the list, The Southern Cookbook: A Manual of Cooking and List of Menus, published in 1912 by S. Thomas Bivins. My fingers went numb. Hurriedly, I moved the cursor over the price, and clicked. And prayed. The page advanced from the $95 price tag to Paypal and I screamed with delight:

“I got it!”

Featuring several hundred recipes, the Bivins book stands out among other African American works of the time as detailed as a textbook, but welcoming like a diary. This “manual of cooking and list of menus and recipes used by noted colored cooks and prominent caterers,” is a comprehensive study of the depth and breadth of the black cook’s repertoire, with formulas that validate the technical skills ordinary cooks possessed, but took for granted. Plus lots and lots of suprises.

From the author we learn: how to bone capon, to brew beer, to clean and dress fresh fish. We are regaled by innovative recipes such as rice pie crust, transparent marmalade, mushroom powder, and vegetable custard with splash of spinach juice. General rules of housekeeping, setting the table and curing the sick fill out his methodology.

I spent the next couple of hours going through my Zerox copy of Bivins’ book in a luxurious afterglow similar to the one Mariah Carey relished on her Butterfly album following an intimate encounter on the Fourth of July. In his Introduction, Bivins whispered his intentions and I swooned:

“In presenting this book to the public it is with the view of supplying the knowledge so much needed and sought for in a practical, condensed way, that shall give the home greater comfort; and the author hopes that after more than twenty years of experience and investigation he may be able to fill in a measure this long felt want.”

Then the unthinkable happened.

An email from Omnivore Books on Food explained that my request to purchase The Southern Cookbook collided with another buyer’s order. Bivins wasn’t really available after all.

So there I was, unfulfilled, left with only the hope that one day I might have my heart’s desire. I consoled myself with Bivins’ swaggering confidence:

“It is said that the mother who rocks the cradle controls the nation, but the domestic who faithfully and intelligently serves her who rocks the cradle is, in fact, the real ruler. Domestic service consists not simply in going the rounds and doing the humdrum duties of the house, but in scientifically cooking the food, in creating new dishes.”

I carry on.

MUSHROOM POWDER

Wash half a peck of large mushrooms while quite fresh and free them from grit and dirt with flannel. Scrape out the back part clean, and do not use any that is worm-eaten; put them in a stewpan over the fire without water, with two large onions, some cloves, a quarter of an ounce of mace, and two spoonfuls of white pepper, all in powder. Simmer and shake them till all the liquor be dried up, but be careful they do not burn. Lay them on tins or sieves in a slow oven, till they are dry enough to beat to powder; then put the powder in small bottles, corked and tied closely, and keep in a dry place.

A teaspoonful will give a very fine flavor to any sauce; and it is to be added just before serving, and one boil give to it after it has been put in.

Oh I’m so sorry you didn’t get those books. Maybe the purchasers will read your post and decide you are really the rightful owner for them. One can hope. xoxo

I recently discovered Bivins’ cookbook while doing work with a British cookbook from the late 1700’s. Unfortunately, it was because the recipes in Bivins are copied whole from Maria Eliza Ketelby Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery (the first American edition from 1807 was probably a pirated copy). In no way do I think this diminishes Bivins’ importance or the importance of his book. But it points to the long and fraught history of copyright in cookbook publishing.

Thanks for this helpful insight, Carrie. I will check into that. You are very right: African American contributions to the American table are very complicated.