Last week on a frigid Thursday evening, I found myself in Harlem surrounded by snow drifts, a dozen Facebook food friends, and inspired Afro-Asian cuisine at Alexander Small’s sexy new restaurant, The Cecil. An ensemble of attentive waiters played their parts with aplomb in the dimly-lit dining room, recommending southern-styled cocktails and dishes that layer classic and global flavors, as we pondered what has changed for blacks in the food industry, what hasn’t and what we can do about it.

I was in New York for a meeting of the James Beard Broadcast Media Awards committee, noticeably agitated by the dearth of African American entries, and fresh off a panel in Austin on the subject of new media, women and food. My thoughts were still swirling around issues of access, increased opportunities, and competition created by the Internet, but I was absolutely delighted by this chance for kinship with talented, up and coming food industry folks who share my fascination with the African American food legacy, and the authors of The Jemima Code.

One of those enthusiasts, culinary historian Michael Twitty, was unable to join us, but he and I will continue the conversation this Saturday when we co-present History Around the Table: African American Cooks and Our Culinary History at the French Legation Museum in Austin. Twitty soared to the forefront of the foodie conscience after writing an impassioned letter to beleaguered Paula Deen and appearing on the PBS special, African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Having spent more than 30 years learning, thinking and writing about food in traditional media, I have been thrilled to celebrate its accolades for Twitty, and now for The Cecil’s Chef de Cuisine Joseph “JJ” Johnson and its opera singer-owner Alexander Smalls. That night, not even the disappointing showing among the award nominees could overshadow the essence of my optimism for the future: professional excellence, coalition building and “fusion cuisine.”

Fusion cooking is the same cultural blending practiced by our ancestors who melded European and African techniques with the indigenous ingredients of the Americas into a hallowed (southern) cuisine. Scholars have used various titles to summarize it — “African grammar,” “wok presence,” “Creolization” — but it took 1990s chefs to apply arts and music terminology to the rich exchange, and to make it stick.

Back then for example, accomplished restaurant and catering chef Jeanette Holley wore her African American fusion sensibilities like a culinary badge of honor. Born to a Japanese mother and a black father, she built her reputation on the best of what each culture had to offer. Ginger and rum spiced sweet potato pie. Asian flavors, such as star anise, coriander, and Szechwan peppercorns dusted barbecued pork spareribs. It was a glorified style that “borrowed parts from each other to develop a new language of their own,” she said in a news article for the Los Angeles Times Syndicate.

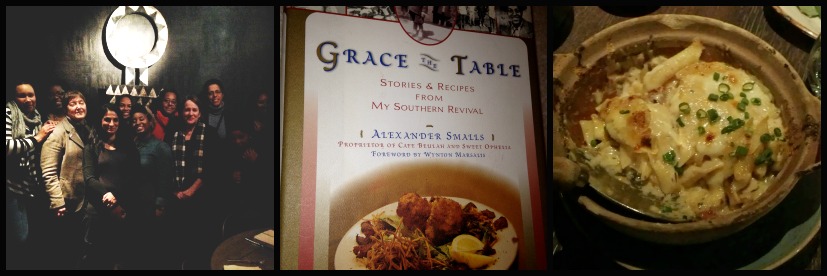

Long before there was The Cecil, the fusion way also made it possible for Smalls to blend his penchant for storytelling and his love of southern food with international flair into acclaimed restaurants and a 1997 cookbook, Grace the Table: Stories & Recipes From My Southern Revival, where Sweet Potato Waffles and Peach Cobbler hold their own alongside Sea Bass Wrapped in Lettuce Leaves and Pork Masala with Mixed Greens.

As trailblazers, all three gentlemen are obviously imaginative and talented and able to show the world what happens when we look back at historic foods and classic cooking methods with reverence, but employ them as stylish flourishes rather than remnants of poverty and survivalist cooking. And, they are living, breathing evidence of the old saying: “Attitude is everything,” whether we are talking about Twitty’s blending of Jewish and African American culinary histories, or Johnson’s Afro/Asian/American Oxtail Dumplings, Collard Green Salad, and Macaroni Cheese Casserole (accented with rosemary, caramelized shallots, and pepper ham), This is certainly good news and a sign of changing times for other aspiring men in food.

So what about women like Holley? Isn’t it time for strong young ladies to enjoy the accolades and benefits associated with artistic blending in the kitchen?

You may already know about the firestorm created by a recent Time Magazine cover story that ignored female chefs in general, but for me it renewed dialogue about the barriers to entry for black women chefs, too.

Disregarding the accomplishments of black women is not new. From the very beginning, traditional media has paid more attention to black men, publishing their recipe books in the trade, maintaining records of their careers in catering, building cooking shows around them, and crowning them with title of “chef” whether they cooked on the Pullman Railroad, on college campuses, in hotel dining rooms, or in the White House.

With new media, however, culinary honor may finally be possible for young female food professionals of color — like my dinner companions — who are standing out, and up for themselves, while promoting and supporting one another. (With encouragement from established industry veterans; thanks Nancie, June, Debbie, Michelle, Ramin and Scott.)

Therese Nelson is a graduate of Johnson and Wales who founded the website Black Culinary History to document industry diversity and provide a space for networking; Elle Simone is a freelance chef and Food Network food stylist who studied at the Culinary Academy of New York and created SheChef, a mentoring program that fosters self-confidence and excellence in culinarily-focused young women from urban settings; Nicole Taylor, a self-described “artisan candy maker, activist, social media maven,” hosts Hot Grease, a progressive food culture radio program on Heritage Radio Network; Sanura Weathers blogs about her food studies and passion for cooking at home; multi-talented, singing chef Jackie Gordon set a tasting of New York artisan chocolate makers to music in her newest show, Chocabaret; chef Nadine Nelson, a culinary educator, community activist and event planner, celebrates world cuisines on two sites, Global Local Gourmet and Epicurean Salon; and Sarah Khan, a journalist at zesterdaily.com hopes to inspire social change around local, national, regional, and global foodways as director of the Tasting Cultures Foundation.

As our evening at The Cecil drew to a raucous close, several of these active “next generation” women leaned in with deep emotion and described her own sense of ambition and dedication sparked by Jemima Code authors — women (mostly) and some men — who lived, worked, and achieved success in the media’s culinary shadows.

My heart filled with hope that someday soon more women of color will be counted among culinary royalty and perhaps win awards for what we accomplish in new and traditional media — or bricks and mortar.

Shrimp Paste with Hot Pepper

Ingredients

- 1/2 pound large shrimp, peeled, deveined, and poached

- 1/2 cup black-eyed peas, cooked

- 1/2 cup chickpeas, cooked

- 3 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 jalapeño pepper, minced

- 1/2 teaspoon cayenne pepper

- Juice of 4 lemons

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 cup mayonnaise

- 1/4 cup cilantro, chopped

- 3/4 cup olive oil

Instructions

Place all ingredients except olive oil in a large bowl of a food processor. Pulse until smooth. With machine running, pour in olive oil and pulse until thickened. Check seasoning. Serve in a medium-sized bowl, accompanied by a breadbasket.

Makes 8 Servings

From Grace the Table: Stories & Recipes From My Southern Revival, by Alexander Smalls

“…My heart filled with hope that someday soon more women of color will be counted among culinary royalty and perhaps win awards for what we accomplish in new and traditional media — or bricks and mortar.”

Wonderfully and thoughtfully said. And a fine meditation on a memorable important evening.

The thing is that Im not sure you understand just how much you mean to us next generation Jemimas. This blog, but really you Miss Toni, and the dedication your life and career has shown us, is everything. We walk in the path you are laying for us, that you sacrificed for and that generations before you laid the blueprint for. We have a baton to grab because women like you and Nancie McDermott and so many others have shown us how to be strong multifaceted women rooted in food and fearsome about our place in it so Thank You for speaking our names, but more thanks you for the Jemima Code and for being the best example of excellence in this work for each of us!!

Thanks so much for including me in this thoughtful and thought provoking recap of a dinner I was thrilled to attend. Thanks to my incredible food loving great grandmas and grandmas on both sides of the color lines for giving me my inheritance, my reverence and joy for cooking and sharing and teaching people about food, love and courage. I felt honored to be amongst such a passionate group of trail blazing women and men.

I second all the emotions here! This post filled my heart with joy and hope. You have set the path for future ‘Jemimas.’ I agree JJ, Twitty and Smalls are changing the food conversations.We can adopt a feeling of reverence about our heritage food without fear.

Friends – your heartfelt emotions make me proud to be the vessel through which our ancestors continue to nurture and inspire. Looking forward to the next steps on our journey together. Thank you.

Ms Toni, you are inspiring the way with your outstanding leadership and dedication to the Women of the Jemima Code.

It was a real privilege to share the meal last Thursday with such passionate women and men who know what they want and where they’re going. <3

What a wonderful meet up, and so looking forward to more ways of collaborating and building, growing stronger and stronger, and supporting each other to tell y/our stories, on y/our own terms…

Hey Toni, I was writing you here and the message disappeared… I’m living in China and was writing about wok presence and got in a conversation with Anne Mendelson who says my concept of it is incorrect, that I need to read Grace Young’s work… she writes about wok hay (hei, or qi in Mandarin), which I think is different. Loved coming upon your site with my old pal Alexander… and here is the great Michael and a comment from Nancie, too… like old home week! So is your quote of wok presence purely from Karen Hess or do you have other sources? I’m fascinated that you group it with African grammar and Creolization… I think of all these things as related but different… Hope this finds you well and happy. Take care, “Hoppin’ John”

Hey there John, great to hear from you. Forgive me for taking soooo long to reply. My quote is directly from Karen. My thinking here is that these concepts are all related, each trying to give name to that mysterious thing that happens when two different people cook the same recipe, whatever their race, age, gender, etc. The dish seldom turns out the same, by any name. Have you learned anything more?

Super Colon Cleanse contains many highly effective herbs, and will or will not be the very best product for you.