LENA RICHARD: HONORED BY JAMES BEARD THEN AND NOW

I went to the safe to retrieve a New York-area author from the Jemima Code cookbook collection to be among the black cooks featured in my pop-up art exhibit at the Greenhouse Gallery at James Beard House in Manhattan. I came out with New Orleans chef Lena Richard. More than 70 years ago, the “father of American cuisine” had been Richard’s advocate. Now, she would return to his home to uplift and encourage a whole new generation.

Until recently I had only briefly studied Richard’s life. I read in a resume of her accomplishments in the exhibition guide at Newcomb College Center for Research on Women at Tulane University, that she was a formally trained culinary student, completing her education at the Fannie Farmer Cooking School in Boston. She ran her own catering company for ten years, operated several restaurants in New Orleans, including a lunch house for laundry workers, cooked at an elite white women’s organization, the Orleans Club, opened a cooking school, and taught night classes while compiling her cookbook.

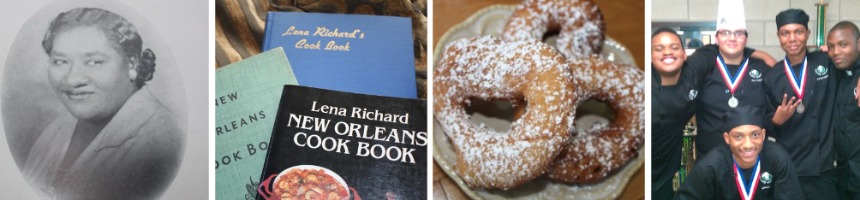

In 1939, she self-published more than 350 recipes for simple as well as elegant dishes in Lena Richard’s Cook Book. Her smiling face radiates from the kind of ladylike portrait one might expect to find cradled inside a gold locket worn close to the heart. A year later, at the urging of Beard and food editor Clementine Paddleford, Houghton Mifflin published a revised edition of her work. This book, however, contained a new title and preface, and that precious cameo-style photograph was gone.

Through the end of April, visitors to Beard House were welcomed into the sanctuaries of unsung culinary heroes like Richard. Screen-printed images of black women at work in and around the kitchen hearth in slave and sharecropper’s cabins, gardens, and in shotgun houses throughout the south hung on the walls of the Greenhouse. The images in this engaging visual history were taken from my historic reprint of a 1904 classic cookbook, The Blue Grass Cook Book — photographs that document culinary contributions to American cuisine and establish an enduring legacy for the women as modern role models who encourage everyone to cook and share real food.

In these times of Top Chef-styled plates where food is stacked, foamed and streaked, it can seem impossible to be impressed by the simplicity of three-course menus comprised of dishes like avocado cocktail, buttered saltines, broiled steak, petit pois, and watermelon ice cream — but we should try.

So, in celebration of the hard-working, nimble chef who taught culinary students how to make homemade vol-au-vent and calas toud chaud while tutoring her daughter in the entrepreneurial skills of business 101, and as part of my outreach to vulnerable children in Austin, and in partnership with the James Beard Foundation, the University of Texas, the Texas Restaurant Association, and Kikkoman, four high school culinary students cooked for a reception featuring chef Scott Barton, April 1 at the Beard House.

For the past three years, students from Pflugerville’s John B. Connally High and Austin’s Travis High have demonstrated professionalism, self-awareness, and pride in the presence of these art works, the kind of outcomes we can expect when we provide culturally-appropriate experiences that engage and inspire kids toward careers in the food industry — whether those jobs are in food archaeology, anthropology, food service, or public health.

Ryan Johnson, a senior at Connally described the meaning of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity this way: “Most people my age have never heard of the James Beard Foundation, or the IACP, but as soon as Chef mentioned those names, I couldn’t believe my ears. I thought. “No way!

“Every night this week, I could hardly sleep because of the anticipation, and thoughts of the different people I’ll meet, and foods I’ll see. My mom always wanted me to be as passionate about food as she is; her wish has come true. I am truly grateful for the wonderful opportunities my passion and hard work have brought me, and I can’t help but think, “I’m actually going to be a chef…”

For information about The Jemima Code exhibit at the James Beard House Greenhouse Gallery, visit:

http://www.jamesbeard.org/index.php?q=greenhouse_gallery

Lena’s Doughnuts

Ingredients

- 2 cups sifted flour

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon each ground nutmeg and cinnamon

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1 egg, well beaten

- 1 tablespoon melted butter

- 1/2 cup milk

Instructions

Sift flour once, measure, add baking powder, salt, nutmeg and cinnamon. Sift together, three times. Combine sugar and egg; add butter. Add flour, alternately with milk, a small amount at a time. Beat after each addition until smooth. Knead lightly 2 minutes on lightly-floured board. Roll 1/3-inch thick. Cut with doughnut cutter. Let rise for several minutes. Fry in deep, hot fat until golden brown. Drain on unglazed paper. Sprinkle with powdered sugar, if desired.

Number of Servings: 12

Comments