by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 27, 2015 | Featured, Uncategorized

This will be the last regular post for The Jemima Code — a blog that turned the spotlight on America’s invisible black cooks and their cookbooks, grew into a traveling exhibit and book available now via the University of Texas Press and spawned a 501c3 nonprofit organization. Three new initiatives, inspired by current events, will take its place.

Over last year’s Thanksgiving weekend, an MSNBC segment with Melissa Harris-Perry shifted attention from outrage and protests over racial profiling in Ferguson, Mo. to racial stereotyping in the food world. The topic of discussion: food, race and identity. Using Jim Crow era imagery and ignored culinary history as the backdrop, a panel of experts introduced viewers to a surprisingly academic food justice dialogue, raising a question black food professionals wrestle with all the time:

What we can learn about who we are when we shake off the shame about how or what we eat?

The gathering included Psyche Williams-Forson, author of Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, & Power, and directed some much-needed attention to the idea of reclaiming ancestral foods as a source of cultural pride. Williams-Forson, whose illuminating scholarship examines the complex relationship between racist and realistic characterizations of our food traditions, acknowledged the destructive legacy associated with negative images of African American food choices. The insightful scholar also pointed to positive aspects of her affirming work that encourage black women to embrace the myriad ways our foremothers used food for economic freedom and independence, community building, cultural work and to develop personal identity.

Take watermelon and fried chicken for instance. Some black folks feel demonized when they eat these foods in public, while chefs in trendy restaurants all around the country earn high dollars for watermelon salad and gluten-free gospel bird. And don’t even get me started talking about the book and blog that made white authors household names when they capitalized on the label “thug” and its new meaning — symbolizing “a slice of the African American urban underclass by others privileged to define them, label them, and take their lives…,” as Michael Twitty stated, while black authors struggle to secure publishing contracts. (You’ll have to read his blog post and the comments about Thug Kitchen on Afroculinaria.com to get the scoop.)

Even with evidence pointing to valuable African American foodways, the discussion ended with frustration as MHP exclaimed: “I feel like we just need to bring joy to eating all of it.”

It was as if “nerdland’s” exasperation (MHP’s self description) parted the Red Sea, offering freedom to culinary history’s slaves through new projects for The Jemima Code.

The first is a follow-up cookbook that Rizzoli will publish in 2016. The Joy of African American Cooking features 400 to 500 recipes tested for today’s home kitchen, tracing the history of dishes created by African American cooks over three centuries, including influences of Africa, the Caribbean, and the American South.

The John Egerton Prize I received from Southern Foodways Alliance inspired what came next. On Juneteenth weekend 2015 we held the first symposium dedicated exclusively to African American foodways in Austin, Texas. The event gathered scholars, researchers, students, journalists, authors, restaurateurs, farmers, chefs, activists, and anyone interested in exploring issues of social injustice through the lens of food for Soul Summit: A Conversation About Race, Identity, Power and Food.

The activities began on Emancipation Day (June 19) with a reception hosted by Leslie Moore’s Word of Mouth Catering with wines by Dotson-Cervantes and the McBride Sisters. We spent the next day and a half eating and drinking together on the grounds of Austin’s Historic Black College Huston-Tillotson University, while discussing the complex intersection of African American foodways traditions and how they have been used to define culture. Well-known and respected African American food industry experts including Jessica B. Harris, Twitty and the soul food scholar, Adrian Miller challenged our thinking about the foods that comprise the traditional African American diet, the ways those foods and the people who prepared them have been characterized and the impact of those representations on our communities. We explored the ways food continues to shape economic opportunities and community wellness and what some folks are doing about it. Renown African American chefs and mixologists, including Bryant Terry, Todd Richards, Kevin Mitchell, BJ Dennis and Tiffanie Barriere excited our palates with traditional, modern, and vegan fare. You can hear highlights, recorded in part, by a grant from Humanities Texas and Imperial Sugar, on SoundCloud.

Finally, I know that everyone can’t open the doors to a restaurant honoring the food and memory of a fabulous cook and relative the way that chef Chris Williams does every week with upscale, bowl-licking shrimp and grits at Lucille’s in Houston. So instead, I hope to reduce food shaming and “bring joy” to cultural eating through an online living cookbook and public archive that also picks up where The Jemima Code’s expanded history leaves off.

It is under construction now, but when business and sociology students are done with it this summer, the website will invite people of every culture to log-in, share recipes, photos, and stories about their favorite invisible cook. In my vision, this diverse group of “Jemimas” will turn the spotlight onto individuals so we can begin to embrace one another without prejudice or as members of a group associated with a particular race or food tradition.

If that’s not enough to spur joy in African American cooking, the comment section will remain open for other suggestions.

Discuss!

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Nov 8, 2011 | Domestics

It is Day 3 of a quick get-away to New Orleans and I am hopping over heaving sidewalks and the mammoth roots of heritage oaks as I jog toward the urban oasis known as Audubon Park in Uptown when up ahead, of all things, I encounter The Help.

Now, instead of the calming anticipation of an escape from the Texas heat and draught, I’m a little grumpy thinking instead about the movie the New York Times described as a “big, ole slab of honey-glazed hokum.”

Again.

The problem is this: Though slightly distorted by the mist of a steamy humid morning, I can see a narrow black woman in uniform as she emerges from a dilapidated Chevy. She waves goodbye to the elder lady behind the steering wheel, makes her way up the cobblestone walk and knocks on the door of an opulent southern mansion. As I jog by, I extend morning greetings to them both and realize that while I have been straining to hear the voices of accomplished Louisiana cooks over the loud and unrelenting gaggle surrounding the record-breaking book and film, real women of color are still reporting to work in the homes of wealthy families in these “post racial” times.

That reality is one of the truths about the complex relationship between American domestic workers and their employers flooding my recent thoughts with the unrestrained fervor of floodwaters from Lake Pontchartrain. And I am not the only one thinking this stuff.

An internet title search of Kathryn Stockett’s exploration of domestic race relations revealed a diverse range of opinions, several fascinating character studies, an open letter to fans posted by the Association of Black Women Historians and a thoughtful review by Audrey Petty in the Southern Foodways Alliance newsletter that compares The Help to a historically accurate text published at the same time, by Rebecca Sharpless entitled, Cooking in Other Women’s Kitchens, Domestic Workers in the South, 1865-1960.

But, it was the broad sweep of reactions I observed at a University of Texas roundtable comprised of Austin students, community members and scholars who gathered to answer the question “What Are We Going to Do About the Help?” that galvanized my resolve to stop fretting about this tiresome fiction and do something productive: Focus on giving life to the unnamed women who really did do America’s cooking in The Jemima Code – The book.

While African American historians and critics are rightly troubled on numerous levels, white audience members seem surprised and even offended by their furor. Whichever side of the debate you are on, one reality is easy to defend: Aibiliene and Minny have stirred a race and food dialogue that gives Jemima Code cooks the opportunity to tell their own sweet, long-suffering truth not just in academia, but with empassioned Americans, too. Finally. Too bad their book won’t be on shelves in time for the holiday DVD release of the film, which is sure to prolong the negative discourse.

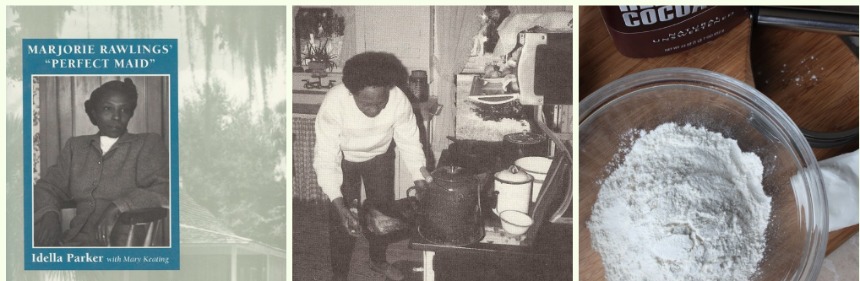

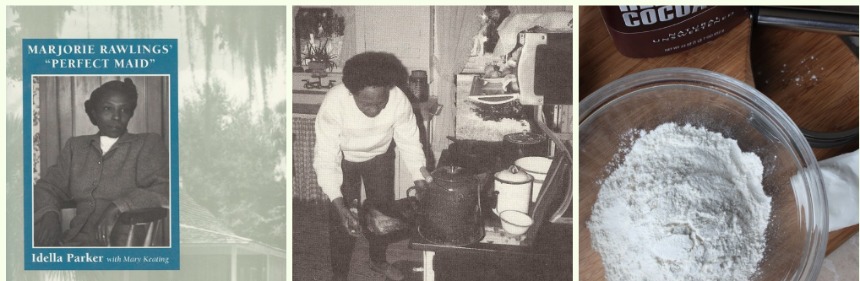

Thankfully, while we await the book, we can learn from Idella Parker.

Although her autobiography does not contain recipes in the traditional sense, Idella’s story accomplishes something unique and wonderful that continues to elude focus groups and institutional reconciliation efforts, scholarly works, well-intentioned cookbooks, and fiction like The Help with its fanciful domestic vibe. Parker draws everyone into the kitchen, inviting them to cook for each other and to persevere through awkward conversations about race when she describes what it was really like to be Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings “Perfect Maid” — a notion the Delany Sisters called, “Having Our Say.”

In 1992, at about the time that I began shopping the idea of The Jemima Code to academic and trade publishers to give voice to the unheard, this former domestic, teacher, and cook was going to press with an ambition similar to mine: telling her own account of life in the household of a popular American novelist.

“Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings called me “the perfect maid” in her book Cross Creek,” Parker wrote in the Preface to Idella, Marjorie Rawlings’ Perfect Maid. “I am not perfect and neither was Mrs. Rawlings, and this book will make that clear to anyone who reads it.”

Parker crafts an insightful look into the complex chemistry that existed between a black cook and her mistress in the late 1930s from memories that are believable, poised, and fair. As the story of their life together unfolds, we hear how it felt to be underpaid and overworked, and of Idella’s courage in the face of blatant racism.

And she is frustrated by this, also: after months together in the kitchen testing recipes for the cookbook, including many that were hers such as the chocolate pie, Idella is given credit for just three of them, including the biscuits.

Nearly 20 years later, fans still rave about Rawlings and her Cross Creek Cookery in reviews, while black cooks stare down jocular characterizations that portray them in aseptic stereotypes that trace back 100 years. In the final words of her autobiography, Idella describes the paradoxical situation like this:

“Our relationship was an unusually close one for the times we lived in. Yet no matter what the ties were that bound us together, we were still a black woman and a white woman, and the barrier of race was always there.

“In private, we were often like sisters, laughing and chatting and enjoying one another’s company. We shared many years together, helped one another through bad times, and rejoiced for each other’s happiness. Between the two of us there was deep friendship and respect, and no thought of the social differences between us.

“But whenever other people were around, the barrier of color went up automatically. Without acknowledging that we were doing so, we became more distant to one another. She became the rich, white lady author, and I became quiet, reserved, and slipped back into her shadow, ‘the perfect maid.’”

Funny thing is, with truth such as this, Parker just doesn’t come off like the kind of woman who would retaliate for bad times by putting shit in the mistress’ chocolate pie.

Would she?

In Her Kitchen

Cross Creek Chocolate Pie

Ingredients

- 1 cup milk

- 1/2 cup granulated sugar

- 1/4 cup all-purpose flour

- 5 tablespoons cocoa powder

- 1/8 teaspoon salt

- 2 eggs, separated

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- 1 (8-inch) baked pie crust

- 1/4 cup powdered sugar

Instructions

Scald the milk in the top of a double boiler. Combine the granulated sugar, flour, cocoa, and salt and whisk into the milk. Beat egg yolks lightly. Stir in the yolks and cook, stirring constantly, until the mixture is well thickened. Remove from heat and cool slightly. Stir in 1/2 teaspoon vanilla. Pour into the baked pie crust. Beat egg whites to soft peaks. Gradually beat in powdered sugar and remaining 1/2 teaspoon vanilla. Beat until stiff peaks form. Spoon meringue onto chocolate filling and bake at 325 degrees 20 minutes, or until lightly browned

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 12, 2011 | Plantation Cooks

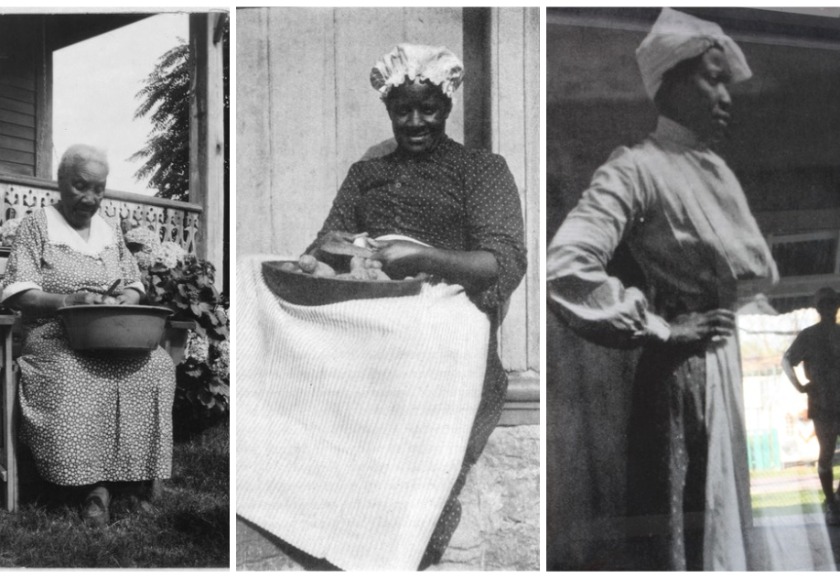

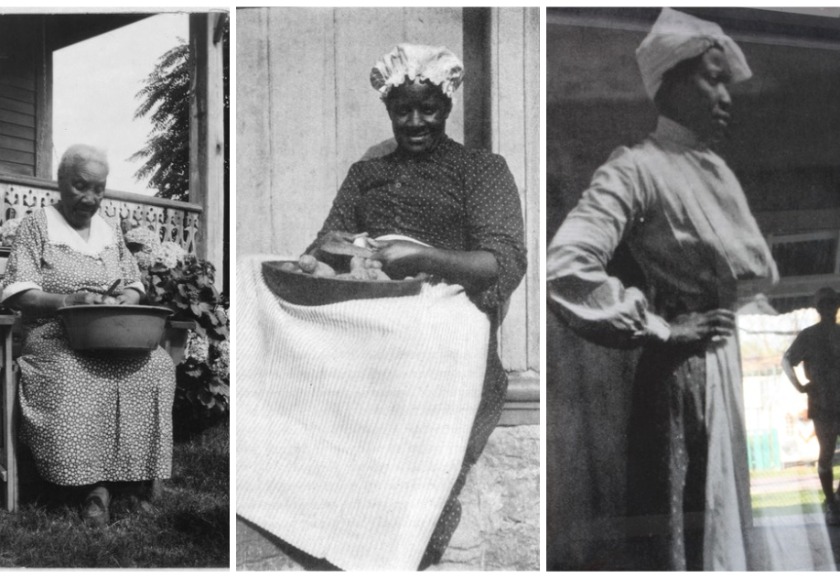

Betty Simmons sits leisurely on the back porch at 2515 Holman, in Houston’s historic Third Ward with a big, round metal pot in her lap and a curtain of voluptuous hydrangeas as her backdrop. She has a small knife in one hand, peeling what appears to be potatoes. Her white hair is brushed back away from her face, revealing a surprisingly supple and healthy look for a woman of nearly 100. The chain link of a porch swing is barely visible beyond the ornate railing.

Betty is one of five Jemima Code women who are on exhibition through June 19, at Project Row Houses, Round 34 Matter of Food. My artist friend and Peace Through Pie partner Luanne Stovall and I are co-curators of Hearth House, a traveling installation where Betty and the cooks of the Blue Grass Cook Book (the Turbaned Mistress, Aunt Frances, Aunt Maria and Aunt Dinah) are capturing the hearts of visitors just about as much as they enchant us.

Some years ago, as I fretted on a Southern Foodways Alliance excursion over the loss of these women, my friend and mentor John Egerton asked me whether they were haunting me. I shared his silly question with some artsy friends who were having their own unique, spiritual responses to the women. Before we knew it, the idea for the Project Row Houses exhibit materialized.

That phenomenal creative team (Ellen Hunt, Meeta Morrison, Luanne and I) digitized and enlarged the women’s images onto seven-foot-tall, transparent screen-like fabric that is suspended from the ceiling in one of seven shotgun-style houses at PRH.

Of course, we all knew that in order to break the code, the space had to be beautiful, so the walls were painted in warm colors that bring thoughts of sweet potatoes, sorghum and sunflowers to mind. The text is minimal — drawn from the inspirational words of Mary McLeod Bethune and from the women themselves. And, a fourth wall, painted in chalkboard paint, provides a space for the community to share kitchen memories and pie stories (which we erase periodically to symbolize the way the women were erased from history). A rough-hewn long table invites guests to linger and to leave their kitchen tales on recipe cards that will become part of our permanent archive.

When the banners were first unrolled, I actually lost my footing and crumbled onto the floor. And cried. I’d spent so many years waiting for these women to finally be honored. To top it off, on our final day of installation, my mother noticed that as I stood on the back porch of the house just beyond the screen of my favorite, the Turbaned Mistress, my silhouette was eerily superimposed into the screen like the shadow of a child, ready for tutelage at her side. Thank goodness she had the sense to photograph the moment. Obviously, the mystery of the women is very personal. And, it is palpable.

Since Opening Day, people visiting the exhibit have written to confess their experiences, too. They tell me how Aunt Frances looks over them in different ways depending upon the sunlight, or when the hot, humid breeze blows through the house at different times of day.

Is there something special to know about Betty?

Betty was one of those extraordinary slave girls, who grew up in the kitchen in the shadow of a phenomenal Texas cook who had absolutely no idea she was saving a child’s life as she passed on culinary skills casually, one meal at a time. But, she did.

Betty was born a slave to Leftwidge Carter in Macedonia, Alabama, then she was stolen as a child and sold to slave traders, who later sold her in slavery here in Texas, where her cooking skills protected her from a harsh life of field labor in slave times, and helped her manage scarce resources in freedom.

She was interviewed at a time when national pursuits – from board games and radio to mystery novels by Agatha Christie – helped Americans escape the rigors of Depression-era living, and field writers for the Federal Writer’s Project recorded the life stories and oral histories of former slaves.

Sadly, the government didn’t think to ask many questions about food and cooking, but I’m not mad at them. Fortunately for all of us, the conversational style of Betty’s narrative gives an intricately detailed look at the precarious life of a slave cook working at a Texas boarding house. I learned a little about humility, charity and self-respect from Betty. And, after months of putting the wrong things first in my life, I’m hoping she will help me get my priorities straight from today forward.

What do her words encourage you to do?

Here is a bit of her story:

When massa Langford was ruint and dey goin’ take de store ‘way from him, day was trouble, plenty of dat. One day massa send me down to brudder’s place. I was dere two days and den de missy tell me to go to the fence. Dere was two white men in a buggy and one of ‘em say I thought she was bigger dan dat,’ Den he asks me, ‘Betty, kin you cook? I tells him I been the cook helper two, three month, [Betty’s aunt Adeline was the Langford’s cook] and he say, ‘You git dressed and come on down three mile to de other side de post office.’ So I gits my little bundle and when I gits dere he say, “gal, you want to go ‘bout 26 mile and help cook at de boardin’ house?

Betty’s narrative ends with a sad revelation that her massa eventually did lose everything he owned to creditors — including his slaves. She and the remaining servants were sent to various traders — some benevolent, some harsh — in Memphis and New Orleans. Eventually, Betty the child winds up in Liberty, Texas, where she conveys a message that still resonates for for everyone trying to make it through difficult times — including me:

We work de plot of ground for ourselves and maybe have a pig or a cuple chickens ourselves…We gits on alright after freedom, but it hard at furst ‘cause us didn’t know how to do for ourselves. But we has to larn.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Apr 6, 2011 | Entrepreneurs

It seems hard to believe that nine months have whizzed by without even a peep from me and the women of the Jemima code. Please forgive us; we’ve been a little busy.

Just this week, we traveled back and forth between Austin and Houston several times, first to introduce a new cook at Prairie View A & M University’s Cooperative Extension annual State Conference and Awards Banquet, then, to install an exhibit at Project Row Houses, where the Blue Grass cooks will be on view for the next two months. In between, there were multiple event planning meetings and nursing a kid recovering from ACL surgery.

Oh my goodness.

Everyone warned me when I started this blog project over a year ago not to put myself under pressure to be brilliant or witty on demand, like pay-per-view. But I am a journalist, for Heaven’s sake! I require a deadline to stay on task. Besides, as far as Jemima tales are concerned, I could go on and on and on.

So what a surprise that after my trip to the White House for Chefs Move, I didn’t go on at all. Instead, I stopped researching new women and accepted way too many opportunities to serve the community — as chair of the host city committee for the 33rd annual conference of the International Association of Culinary Professionals, and vice president for Foodways Texas, a new organization modeled after Southern Foodways — all while teaching kids to like the taste of kohlrabi everyday after school. The University of Texas honored the nonprofit cooking organization I founded with a service award for all of those healthy kiddy cooking classes, but my heart beat louder and louder for more Jemima tales.

What would you do? What Jemima would do, of course.

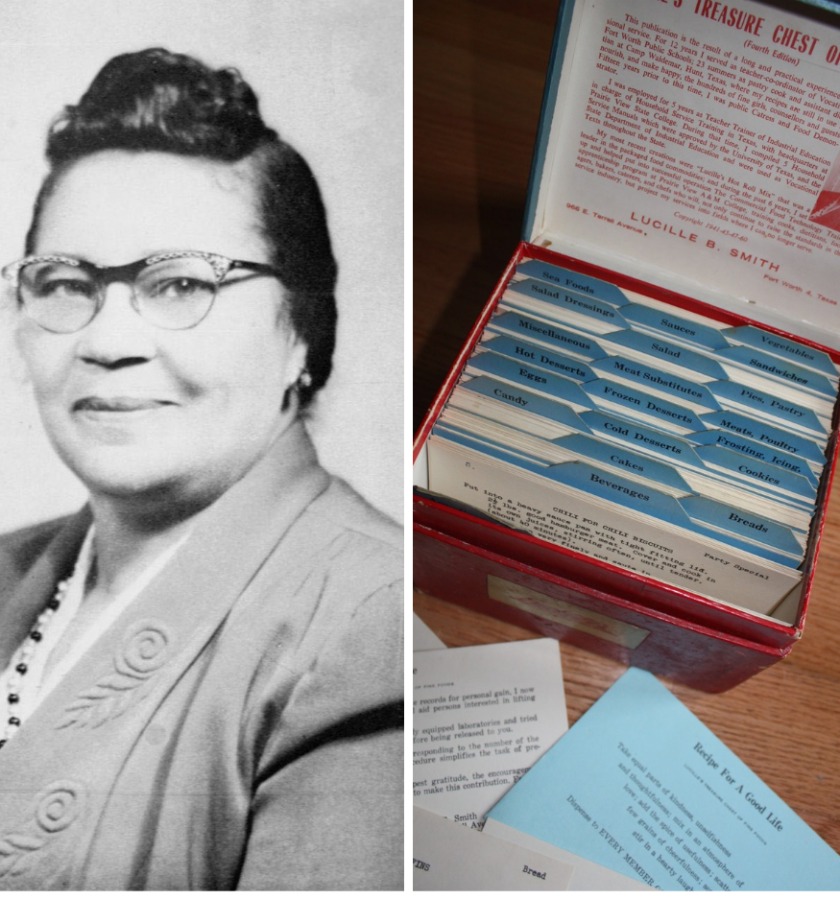

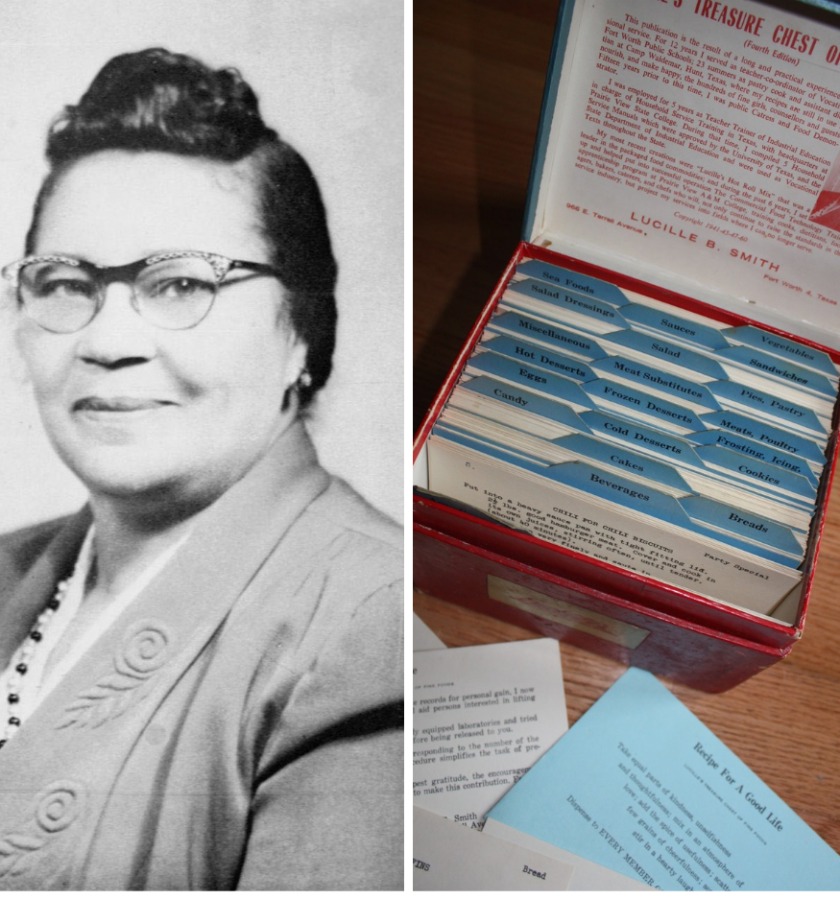

I started sharing “my girls” with live audiences too, presenting Jemima as a role model at meetings of the Culinary Historians of Southern California, the National Forum for Black Public Administrators, and Slow Food Austin. I also told a grateful Prairie View audience about an inspirational woman with an inventory of professional culinary accomplishments and community work so long the city of Ft. Worth honored her with a day named just for her. Her name was Lucille Bishop Smith.

This was a good week for Lucille’s whispered wisdom.

For me, this Tarrant County native upheld the African American cook’s nurturing character while teaching the value of discipline, confidence, and creative thinking during difficult times. Not coincidentally, her profile demonstrated numerous ways that organizational, technical, and managerial skills can be added to the profile of American black cooks.

Lucille lived productively, establishing herself as a respected professional with a local and state reputation during the Great Depression, and publishing more than 200 delicious recipes for simple, as well as elegant cookery, in Lucille’s Treasure Chest of Fine Foods. She raised funds for community service projects, fought to raise standards in slums, developed culinary vocational programs in Ft. Worth and at Prairie View, was responsible for the first extension workers being employed in Tarrant County, brought the first packaged Hot Roll Mix to market, conducted Itinerant Teacher Training Classes, developed Prairie View’s Commercial Cooking and Baking Department, compiled five manuals for the State Dept. of Industrial Education, and was foods editor of Sepia Magazine. And all of that is just part of her resume. Her bio concludes:

“She represents a faithful wife, a devoted mother; a devout Christian, a character builder, a successful business woman, a pioneer in education ventures and a dedicated servant of people.”

Lucille’s Treasure Chest epitomized her life’s work to empower others by using food as a tool to achieve social uplift. In the Preface, she encourages women of the community to follow in her footsteps with this Recipe For A Good Life:

Take equal parts of kindness, unselfishness and thoughfullness;

mix in an atmosphere of love;

add the spice of usefulness;

scatter a few grains of cheerfulness;

season with smiles;

stir in a hearty laugh, and

Dispense to EVERY MEMBER OF YOUR FAMILY

by Toni Tipton-Martin | May 19, 2010 | Domestics

I didn’t mean to make anyone cry. Quite the contrary. I write thejemimacode to honor invisible women and to celebrate — as in party over here! But recently, more followers of this space are sharing intimate stories off-line of the women whose cooking made them feel special. Now, however, thinking about how unfairly the women were treated makes them terribly sad. Reconciliation can do that.

So, I’m here to cheer you up with news that after the hurt comes the heal, at least that is what we experienced following difficult dialogue at gatherings of the Southern Foodways Alliance. I also want to share the uplifting story of two women who came together to preserve the work of one of those obscure cooks in Rebecca’s Cookbook.

In 1942 while the world was at war, Rebecca West was traveling the country with her “lady” amassing a treasure-trove of receipts and recording her escapades in the local newspaper. That “lady,” known only by the initials E.P. helped West record dozens of dishes, from from terrapin to pate de fois gras, as well as childhood recollections of her visits to South Carolina and miscellaneous ruminations about the Bahamas.

Thankfully, E.P. did not resort to the demeaning Jemima stereotype when she transcribed West’s thoughts and recipes. Yes, West speaks in the broken English that is evidence of a rural upbringing, but she is not portrayed by the maliciously exaggerated speech we’ve seen in recent posts. No elitism here either. E.P. obviously respected West’s knowledge and talent, making no claims to her recipes and stating in a brief editor’s note that “Rebecca is so noted for her terrapin, that it is only right for terrapin to have a separate section all it’s own in her cook book.”

West also tells us a bit about their cozy relationship in numerous references to their experiences together in the kitchen. As the introduction to the Fish section, which features examples of modern cuisine such as red snapper fillets sauteed in olive oil, herbs and shallots, then braised in a tomato cream sauce; stuffed baked black bass; sauteed sea scallops; and scalloped oysters, West offers the following amusing tale.

“One night when my lady was out to dinner the butler came runnin downstairs all out of breath. He said, “The lady said she had the best fish tonight at dinner that she ever had an she wants you to try to fix somethin like it.” I says, “Now wait a minute, wait a minute. How does she know it was fish she was eatin?”

He says, “She said she could only see the tail of the fish stickin up out of a cream sauce an she don know what kind of fish it was, but it was good. You better figure out what it was, Rebecca.”

“So I got to figurin…I know the lady who does the cookin where my lady was havin dinner, so I says to the butler, “Joe you skip over there an ask her will she oblige me with the recipe for the little fish with cream sauce they had for dinner tonight…Just as I expected, the dish wasn’t made of little fish at all. It was ham. My lady was so surprised when I told her. She says, “That’s what comes of dinin by candlelight.”

Anyways here’s some receipts which is really fish…”

Precious, isn’t she?

Anyways, after a quick flash in a hot skillet, Rebecca layers red snapper fillets in a baking dish and covers with a cream sauce before baking. We don’t eat much cream at my house so I adapted Rebecca’s snapper to suit my family’s tastes and today’s demand for food that is light, fast and hassle-free. I started with my kids’ favorite way with spinach (lightly sauteed with a little garlic and onion), then used the mix as a bed for rolled and stuffed fillets. Rolling the fish is beautiful and makes dinner seem special. A quick steam, some hot cooked rice, and a healthy dinner is done. Thanks, my ladies.

In Her Kitchen

Red Snapper Roulades with Spinach

- 4 red snapper fillets, skinned and boned

- Salt, pepper

- 1/4 cup prepared spinach dip, about

- 1 tablespoon each olive oil and butter

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 large shallot, minced

- 1 pound fresh baby spinach, rinsed and drained

Instructions

- Season fillets lightly with salt and pepper. Place fillets skinned-side-up on a board. Spread each fillet with 1 tablespoon dip. Roll fillets to enclose dip, beginning with the widest end of the fillet. Secure fish rolls with a wood pick and set aside. Heat oil and butter in a large skillet until sizzling. Add garlic and shallot and saute until tender. Add spinach to the pan and cook about 5 minutes until wilted but still bright green. Place fish rolls on top of spinach. Cook, covered, over medium heat, 10-15 minutes, or until fish is no longer opaque. Remove wood picks before serving.

Note: Do not dry spinach leaves completely. The moisture from rinsing provides the steam that cooks the fish without over cooking the spinach.

Number of servings: 4

In Her Kitchen

Comments