by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 27, 2015 | Featured, Uncategorized

This will be the last regular post for The Jemima Code — a blog that turned the spotlight on America’s invisible black cooks and their cookbooks, grew into a traveling exhibit and book available now via the University of Texas Press and spawned a 501c3 nonprofit organization. Three new initiatives, inspired by current events, will take its place.

Over last year’s Thanksgiving weekend, an MSNBC segment with Melissa Harris-Perry shifted attention from outrage and protests over racial profiling in Ferguson, Mo. to racial stereotyping in the food world. The topic of discussion: food, race and identity. Using Jim Crow era imagery and ignored culinary history as the backdrop, a panel of experts introduced viewers to a surprisingly academic food justice dialogue, raising a question black food professionals wrestle with all the time:

What we can learn about who we are when we shake off the shame about how or what we eat?

The gathering included Psyche Williams-Forson, author of Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, & Power, and directed some much-needed attention to the idea of reclaiming ancestral foods as a source of cultural pride. Williams-Forson, whose illuminating scholarship examines the complex relationship between racist and realistic characterizations of our food traditions, acknowledged the destructive legacy associated with negative images of African American food choices. The insightful scholar also pointed to positive aspects of her affirming work that encourage black women to embrace the myriad ways our foremothers used food for economic freedom and independence, community building, cultural work and to develop personal identity.

Take watermelon and fried chicken for instance. Some black folks feel demonized when they eat these foods in public, while chefs in trendy restaurants all around the country earn high dollars for watermelon salad and gluten-free gospel bird. And don’t even get me started talking about the book and blog that made white authors household names when they capitalized on the label “thug” and its new meaning — symbolizing “a slice of the African American urban underclass by others privileged to define them, label them, and take their lives…,” as Michael Twitty stated, while black authors struggle to secure publishing contracts. (You’ll have to read his blog post and the comments about Thug Kitchen on Afroculinaria.com to get the scoop.)

Even with evidence pointing to valuable African American foodways, the discussion ended with frustration as MHP exclaimed: “I feel like we just need to bring joy to eating all of it.”

It was as if “nerdland’s” exasperation (MHP’s self description) parted the Red Sea, offering freedom to culinary history’s slaves through new projects for The Jemima Code.

The first is a follow-up cookbook that Rizzoli will publish in 2016. The Joy of African American Cooking features 400 to 500 recipes tested for today’s home kitchen, tracing the history of dishes created by African American cooks over three centuries, including influences of Africa, the Caribbean, and the American South.

The John Egerton Prize I received from Southern Foodways Alliance inspired what came next. On Juneteenth weekend 2015 we held the first symposium dedicated exclusively to African American foodways in Austin, Texas. The event gathered scholars, researchers, students, journalists, authors, restaurateurs, farmers, chefs, activists, and anyone interested in exploring issues of social injustice through the lens of food for Soul Summit: A Conversation About Race, Identity, Power and Food.

The activities began on Emancipation Day (June 19) with a reception hosted by Leslie Moore’s Word of Mouth Catering with wines by Dotson-Cervantes and the McBride Sisters. We spent the next day and a half eating and drinking together on the grounds of Austin’s Historic Black College Huston-Tillotson University, while discussing the complex intersection of African American foodways traditions and how they have been used to define culture. Well-known and respected African American food industry experts including Jessica B. Harris, Twitty and the soul food scholar, Adrian Miller challenged our thinking about the foods that comprise the traditional African American diet, the ways those foods and the people who prepared them have been characterized and the impact of those representations on our communities. We explored the ways food continues to shape economic opportunities and community wellness and what some folks are doing about it. Renown African American chefs and mixologists, including Bryant Terry, Todd Richards, Kevin Mitchell, BJ Dennis and Tiffanie Barriere excited our palates with traditional, modern, and vegan fare. You can hear highlights, recorded in part, by a grant from Humanities Texas and Imperial Sugar, on SoundCloud.

Finally, I know that everyone can’t open the doors to a restaurant honoring the food and memory of a fabulous cook and relative the way that chef Chris Williams does every week with upscale, bowl-licking shrimp and grits at Lucille’s in Houston. So instead, I hope to reduce food shaming and “bring joy” to cultural eating through an online living cookbook and public archive that also picks up where The Jemima Code’s expanded history leaves off.

It is under construction now, but when business and sociology students are done with it this summer, the website will invite people of every culture to log-in, share recipes, photos, and stories about their favorite invisible cook. In my vision, this diverse group of “Jemimas” will turn the spotlight onto individuals so we can begin to embrace one another without prejudice or as members of a group associated with a particular race or food tradition.

If that’s not enough to spur joy in African American cooking, the comment section will remain open for other suggestions.

Discuss!

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jun 20, 2014 | Featured, Kitchen Tales

What do you do when you discover something unknown to most people? You make a documentary, of course. At least that’s what my friend Adrian Miller has decided to do, and I hope you will support his very special project.

In my February 28th post, I introduced you to Adrian and urged you to read his book Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time. Since then, Soul Food won the 2014 James Beard Foundation Award for Reference and Scholarship, and just this week, Addie Broyles interviewed us for an Austin-American Statesman feature story about Juneteenth foods, including red soda water. In September, Adrian and I will share the stage at the Eat. Drink. Write. Memphis., in Tennessee, and we’re hoping to tell the story of America’s invisible black cooks next spring in Washington, D.C.

But today, I want to tell you about Adrian’s next important work: a television documentary about African American presidential chefs.

While writing Soul Food, he discovered that every U.S. president has had an African American working in their kitchen, and he’s got their stories and recipes. Adrian will profile several women (pictured above) who cooked for Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison (Dolly Johnson, circa 1887, left), Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt (Elizabeth “Lizzie” McDuffie, maid and part-time cook), and Lyndon Johnson (Zephyr Wright). (You can read more about these cooks in an essay Adrian wrote for our friend Ramin Ganeshram’s America I Am Pass It Down Cookbook.)

It’s no surprise to me that the Jemima Code runs through the White House basement!

Adrian has an active Kickstarter campaign for this documentary, tentatively titled, The President’s Kitchen Cabinet. His idea is to film a trailer that can be used to pitch the show to television network executives. He’s already raised more than 75% of the $10,000 goal, and now the campaign is in its final days (ends at midnight on June 26th).

Ordinarily, it is enough for me to share the stories of amazing women (and a few men) and their gifts to American cuisine on this blog. And, I might even give you a cute little red sticker, emblazoned with the declaration “Bringing Back the Bandana” as your badge of ambassadorship when you attend a Jemima Code talk and are moved by its hopeful message of racial reconciliation at table.

But this week, as we celebrate Juneteenth and its promise of a better tomorrow, I’m asking that you please take a moment to check out Adrian’s Kickstarter campaign, make a donation (no matter how small), and share it with others.

Together, we can help get this important work on the air in time for President’s Day 2016!

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 8, 2014 | Entrepreneurs, Featured, Soul Food Cooks, The Modern Kitchen

“Rise up, ye women that are at ease! Hear my voice ye careless daughters! Give ear to my speech.”

— Isaiah 23:9

You may have been surprised to see so few posts about women last month on a blog that is named after a woman.

From memorable historic figures, to my friends Michael Twitty and Adrian Miller, February was a time to celebrate the achievements of male African American food industry professionals — written history makes it so much easier to report the culinary accomplishments of men. W. E. B. Dubois, for example, praised male caterers in his sociological study, The Philadelphia Negro, while the personal papers of Presidents Washington and Jefferson elevated male kitchen workers from slave to chef status — ignoring Edith Fossett’s legacy of French cuisine, once characterized by Daniel Webster as “good and in abundance.”

It is time to get back to The Ladies.

To celebrate Women’s History Month, the Jemima Code exhibit hits the road tomorrow, sharing life-changing culinary truths, and rewriting black women’s history, one recipe and one audience at a time.

Our first stop is part of a series of events hosted by the University of North Carolina – Charlotte’s Center for the Study of the New South, which will explore the history of race in southern kitchens and includes a two-day conference in September entitled: “Soul Food: A Contemporary and Historical Exploration of New South Food.” Then we are off to Chicago for the 36th annual conference of the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP).

“The Jemima Code fits into the Center’s study of new south food by bringing life to the untold history, triumphs and struggles of one of the primary groups, African American women, associated with what we call southern food,” said Jeffrey Leak, director of the Center and Associate Professor of English. In presenting the Jemima Code in multiple settings — campus, church, and museum — the University hopes to demonstrate its commitment to community engagement and to sharing knowledge with other institutions in the community, Leak explained. “In doing so, we create the possibility of improving upon or creating relationships with these institutions that will lead to collaborative approaches to some of our communities most difficult challenges.”

Jemima Code events kick off with a talk and tea hosted by UNCC and the Social Justice Ministry at Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, featuring the memories of a former slave from Asheville, Fannie Moore. In her WPA interview, Moore details the family technique for preserving peaches showing us how slaves practiced local, seasonal, organic and sustainable living and underscoring the message: “claim your heritage to reclaim your health.”

Next, we’re off to a meeting with students in UNCC’s College of Liberal Arts & Sciences focused on a few ways recipes and cookbooks preserve identity. We will uncover evidence of entrepreneurial and personal values like industriousness and discipline in Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which the former slave observed in her grandmother, a cookie vendor.

On Monday, at an intimate reception, conversation and Jemima Code exhibit at the Levine Museum of the South, guests will be surprised and amazed by African American kitchen proficiencies in stories told by author and R & B singer Sheila Ferguson.

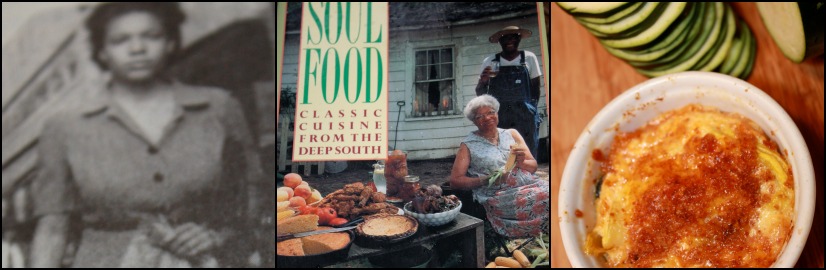

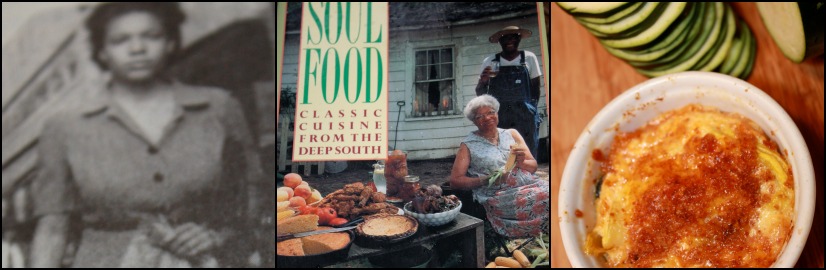

In her 1989 cookbook, Soul Food Classic Cuisine from the Deep South, the former lead singer for the Three Degrees writes in a fast-talking, jive-style that is complete with snappy expressions and memories of cooking and eating at home with family and friends. She has a theory that cooking the soul food way means “you must use all of your senses. You cook by instinct, but you also use smell, taste, touch, sight, and particularly, sound…these skills are hard to teach quickly. They must be felt, loving, and come straight from the heart and soul.” To prove it, she esteems family members, including her Aunt Ella from Charlotte, writing about brilliant dishes of animal guts smothered with rich cream gravy in a colorful rhythm that might just make you want to run out and trap a possum. For real.

Finally, a conversation at IACP on March 16 will explore lessons in culinary justice taught by iconic Chicagoland cookbook authors, like Freda DeKnight. Food writer Donna Pierce helps me set the table with her research on the culinary industry’s middle class. We wrap up with an interactive workshop that I hope will spur Jemima Code audiences to enact what they discover about black cooks, with inspiration from these adapted words of abolitionist Lydia Maria Child:

“For the sake of my culinary sisters still in bondage…”

In Her Kitchen

Aunt Ella’s Squash Bake with Cheese

Ingredients

- 5 cups sliced thin-skinned yellow squash

- 3 tablespoons butter or margarine

- 1/4 cup chopped green pepper

- 1/4 cup chopped onion

- 1/4 cup chopped celery

- 1 (10.5-ounce) can cream of mushroom soup

- 1 egg, slightly beaten

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 teaspoon black pepper

- 1/2 cup grated Cheddar cheese

- 1/4 cup fresh breadcrumbs

- Paprika, optional

Instructions

Cook the squash in 1/4 to 1/2 cup water for 10 to 15 minutes or until fork tender. Drain well and puree it. Melt 2 tablespoons butter in a skillet over medium yeat and sauté your onion, celery, and green pepper until soft, about 5 minutes. Add the soup, undiluted, and cook, stirring constantly, until the soup is smooth and well-blended with the vegetables.

*Serves 6-8

Preheat your oven to 375 degrees.

In a medium-sized bowl, mix but do not beat your squash puree, soup and vegetable mixture, with the egg, salt, pepper, and half of the cheese. Pour into a well-greased 1 1/2 quart baking dish. Mix the remaining butter with the breadcrumbs and the rest of the cheese, and spread this over the top of the squash. Sprinkle with paprika if desired. Bake in the oven for 35 to 45 minutes or until your squash bake is brown and bubbly.

Variation: Do not puree squash. Substitute evaporated skim milk, 2 eggs and 1-2 tablespoons melted butter for the canned soup and 1 egg.

Aunt Ella is one of the finest soul food cooks in our family and she makes squash taste like something out of this world. If you can’t find the right kind of squash this is almost as good made with courgettes.

Adapted from Soul Food: Classic Cuisine from the Deep South, by Sheila Ferguson

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Feb 28, 2014 | Featured, Soul Food Cooks

It didn’t take much to bring the soul food debate raging back into the limelight — Black History Month and a fried chicken, watermelon and cornbread lunch planned at a California Catholic school. Critics were outraged, but I don’t blame the students at the all-girls’ school for recommending a menu composed of heritage foods; I blame the grown-ups.

For more reasons than I can address in this space, soul food has an image problem, and many adults have a love-hate relationship with it, provoked by years of propaganda that used cabin cooking and stereotypes to denigrate black people — marginalizing our foods as dirty and nasty, something you eat with your hands.

So, what follows is a rant and a challenge, summarized by a hilariously funny post about this news story written by a Facebook friend of mine:

“This is ridiculous! I’m outraged! Do you have hot sauce?”

Soul food is a tale of two worlds, bound to a complicated history, as my friend Adrian Miller writes in the introduction to his intelligent book, Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine — made up of stereotypes, poor ingredients, making-do, the low status of blacks, racial stigma, resourcefulness, ingenuity, and communal spirit; denounced as a diet for “slumming” or death. Or both.

If there is such a thing as a “soul food code,” Miller certainly cracked it with this thoughtful endeavor to give soul food a “very public makeover.” To help us think differently about soul food, the writer, attorney and certified barbecue judge poses a few questions:

“What are the important soul food menu items?” “How does a food get on the soul food plate?” And, what does all of that mean for African America culture and American culture?” The surprising answers might just quiet the fury.

“I do hope that through greater understanding about soul food — how and why it developed — the cuisine gets valued as a treasure, and we are not so quick to jettison it as cultural baggage,” Miller said.

Last week, I had a couple of experiences that demonstrated ways this “save soul food” message is getting through, at least here in Austin.

The first was a Cultural Heritage Supper Club dinner that my son and I attended. For the gathering, teens and their moms saluted black culinary achievement with a wide assortment of dishes representing the full African American food experience. The buffet was laden with a fusion of dishes that combined African and European techniques with American ingredients, and ranged from starters to desserts: pimiento cheese-stuffed celery, chicken wings, gumbo, macaroni and cheese, black-eyed peas, greens, tossed salad, West Indian chicken roti, sweet potato pie. Noticeably absent were the poverty foods that polarized the black community and seem to be paralyzing everyone else — salt pork, green beans, pork hocks, collards, pig tails, beans, pig ears, cracklin’ cornbread, pigs feet, black eyed peas, fried chicken, pig jowls, barbecue, pickled pork, candied yams, side meat, mac and cheese, bacon, and sticky sweet desserts.

A few days later, I joined elected officials, public servants, restaurateurs, and other “soul foodies” at Manor High School’s first annual Black History Month soul food competition and lunch. This is a new tradition that encouraged district faculty, staff and culinary students to share their favorite recipes and family history with hopes that food might bring together and build up the small town’s diverse community, according to Rob McDonald, the school’s culinary arts instructor.

McDonald and a district manager reduced their risk for the type of backlash that stunted celebration efforts in California by involving the neighborhood in preserving their cultural culinary traditions, and then recommending “healthier substitutes” to update those shared family heirlooms.

“We want to encourage the students (and the community) to consider food “from the soul” and to adapt it from their heritage keeping the story,” McDonald explained. “The stories that come from the family are part of the overall appeal [of soul food].”

The contest entries included everything I tasted at the teenagers’ supper club, and more: potato salad, red beans and rice, navy beans and cornbread, pig ears, sautéed greens with red bell peppers, banana pudding, coconut cake. The bill of fare also included an inspiring message, passionately presented by Anterrica Culbert, a 12th grader with hopes of attending Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts:

“Soul food is not just about food. It is what happens around the kitchen table and where we learn our family traditions that keep us going on our journey of life. It’s the recipe that has no recipe (a little bit of this and a little bit of that) without measuring…As we celebrate Black History Month we honor and remember those who passed down these wonderful recipes and in doing so fed our souls.”

I was in the grocery store when Cublert’s words collided in my mind with Miller’s scholarship and the sentiments written by 1960s cookbook authors, leading me to an AHH-Ha, make-do moment: it’s not the ingredients or the dishes that make soul food special and worth celebrating; it is the heart attitude AND culinary aptitude.

It all started in the produce section of the grocery store, where, to my surprise, I encountered the most beautiful, fresh-from-the-garden cauliflower, nestled deep inside a cradle of bright green leaves. At home, as I trimmed the leaves and tossed them into my compost bucket, the spirit of Jemima Code’s soul authors came to mind and touched my spirit, reminding me of one their prudent cooking lessons that says nothing goes to waste.

Without really thinking, I retrieved the leaves from the bucket, refreshed them in cool running water, then sliced them into a fine chiffonade, as in the Brazillian manner, and voila: couve. My adaptation of sautéed collards emerged from the reservoir of recipes in my memory, seasoned until it tasted just the way I wanted — not according to a formula or some African American natural instinct. It was the same kind of improvised cuisine our ancestors practiced when they crafted delicacies from homely ingredients — soul.

But, my cauliflower couve does not represent my full culinary ability any more than cabin cooking or soul foods express the contours of a black cook’s kitchen. It does represent learned skill.

In each of these cases, soul food emerges as a personal expression based upon the cook’s history and knowledge and whatever ingredients are at hand. When we remember these inspirational kitchen characters and their monumental accomplishments during Black History Month, young students like Culbert are free to pursue their dreams.

If grown ups will get out of the way and build up African American food history Culbert might one day be the owner/operator of a popular heritage restaurant, such as the Bay Area’s Brenda’s French Soul Food, where diners wait two hours to be seated and served fried chicken, cornbread, and probably, watermelon.

…now go ahead — debate!

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Feb 7, 2014 | Caterers, Featured

Did you ever want something so bad it hurt? That’s how I feel about the last four First Edition African American cookbooks remaining on my Jemima Code shopping list. These extremely rare volumes are all that stands between me and a complete re-write of African American culinary history, told in the voices of the people who did the cooking.

But, this is the story of unrequited love.

My collection includes facsimile copies of these vintage works, and thanks to curators at the University of Michigan and Radcliffe University, I have held these precious gems in my hands, close to my heart. I can still remember how it felt to run my fingers over the gilded lettering engraved on the smooth surface of the cloth boards. I got cold chills as I opened the covers, exposed the fragile, yellowing pages, and uncovered hidden treasure.

Published in the years before and after the turn of the twentieth century, the recipe collections are the rarest of the rare. They are valuable to my mission because they reveal the true Knowledge, Skills and Abilities (KSA’s) possessed by black cooks, whether they were former slaves or free people of color.

It should make no difference that my copies are reproductions. But I want originals. The real thing. Badly. There is just something indescribable about owning such important pieces of history.

Last week, two of the books turned up in an online antiquarian bookseller’s catalog while I was driving to my office downtown. It had only been three hours since the announcement, but the most precious of the books — What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Southern Cooking — was already gone by the time I settled in and logged on. I recovered quickly from the shock of finding a volume published in 1881 by a former slave, Abby Fisher, for the low, low price of $4000.

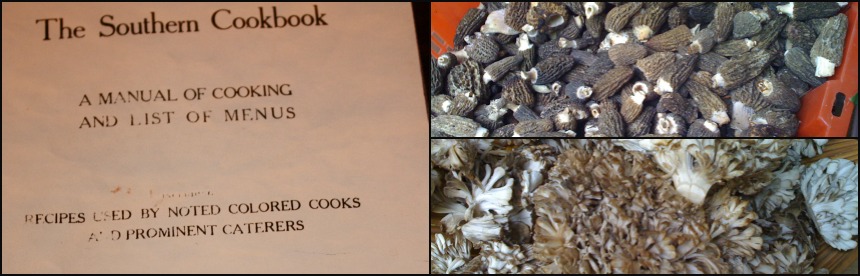

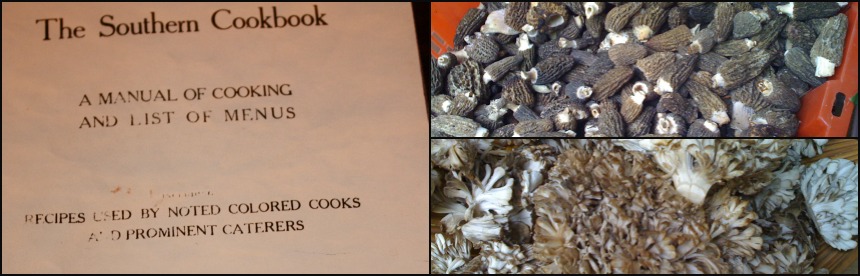

I scrolled to the next entry on the list, The Southern Cookbook: A Manual of Cooking and List of Menus, published in 1912 by S. Thomas Bivins. My fingers went numb. Hurriedly, I moved the cursor over the price, and clicked. And prayed. The page advanced from the $95 price tag to Paypal and I screamed with delight:

“I got it!”

Featuring several hundred recipes, the Bivins book stands out among other African American works of the time as detailed as a textbook, but welcoming like a diary. This “manual of cooking and list of menus and recipes used by noted colored cooks and prominent caterers,” is a comprehensive study of the depth and breadth of the black cook’s repertoire, with formulas that validate the technical skills ordinary cooks possessed, but took for granted. Plus lots and lots of suprises.

From the author we learn: how to bone capon, to brew beer, to clean and dress fresh fish. We are regaled by innovative recipes such as rice pie crust, transparent marmalade, mushroom powder, and vegetable custard with splash of spinach juice. General rules of housekeeping, setting the table and curing the sick fill out his methodology.

I spent the next couple of hours going through my Zerox copy of Bivins’ book in a luxurious afterglow similar to the one Mariah Carey relished on her Butterfly album following an intimate encounter on the Fourth of July. In his Introduction, Bivins whispered his intentions and I swooned:

“In presenting this book to the public it is with the view of supplying the knowledge so much needed and sought for in a practical, condensed way, that shall give the home greater comfort; and the author hopes that after more than twenty years of experience and investigation he may be able to fill in a measure this long felt want.”

Then the unthinkable happened.

An email from Omnivore Books on Food explained that my request to purchase The Southern Cookbook collided with another buyer’s order. Bivins wasn’t really available after all.

So there I was, unfulfilled, left with only the hope that one day I might have my heart’s desire. I consoled myself with Bivins’ swaggering confidence:

“It is said that the mother who rocks the cradle controls the nation, but the domestic who faithfully and intelligently serves her who rocks the cradle is, in fact, the real ruler. Domestic service consists not simply in going the rounds and doing the humdrum duties of the house, but in scientifically cooking the food, in creating new dishes.”

I carry on.

MUSHROOM POWDER

Wash half a peck of large mushrooms while quite fresh and free them from grit and dirt with flannel. Scrape out the back part clean, and do not use any that is worm-eaten; put them in a stewpan over the fire without water, with two large onions, some cloves, a quarter of an ounce of mace, and two spoonfuls of white pepper, all in powder. Simmer and shake them till all the liquor be dried up, but be careful they do not burn. Lay them on tins or sieves in a slow oven, till they are dry enough to beat to powder; then put the powder in small bottles, corked and tied closely, and keep in a dry place.

A teaspoonful will give a very fine flavor to any sauce; and it is to be added just before serving, and one boil give to it after it has been put in.

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Mar 11, 2012 | Entrepreneurs, Featured

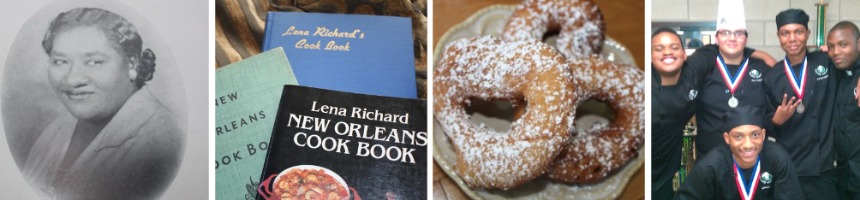

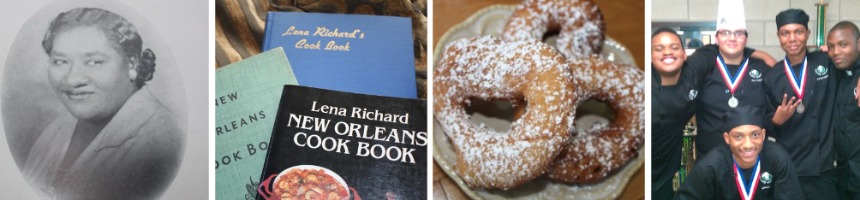

I went to the safe to retrieve a New York-area author from the Jemima Code cookbook collection to be among the black cooks featured in my pop-up art exhibit at the Greenhouse Gallery at James Beard House in Manhattan. I came out with New Orleans chef Lena Richard. More than 70 years ago, the “father of American cuisine” had been Richard’s advocate. Now, she would return to his home to uplift and encourage a whole new generation.

Until recently I had only briefly studied Richard’s life. I read in a resume of her accomplishments in the exhibition guide at Newcomb College Center for Research on Women at Tulane University, that she was a formally trained culinary student, completing her education at the Fannie Farmer Cooking School in Boston. She ran her own catering company for ten years, operated several restaurants in New Orleans, including a lunch house for laundry workers, cooked at an elite white women’s organization, the Orleans Club, opened a cooking school, and taught night classes while compiling her cookbook.

In 1939, she self-published more than 350 recipes for simple as well as elegant dishes in Lena Richard’s Cook Book. Her smiling face radiates from the kind of ladylike portrait one might expect to find cradled inside a gold locket worn close to the heart. A year later, at the urging of Beard and food editor Clementine Paddleford, Houghton Mifflin published a revised edition of her work. This book, however, contained a new title and preface, and that precious cameo-style photograph was gone.

Through the end of April, visitors to Beard House were welcomed into the sanctuaries of unsung culinary heroes like Richard. Screen-printed images of black women at work in and around the kitchen hearth in slave and sharecropper’s cabins, gardens, and in shotgun houses throughout the south hung on the walls of the Greenhouse. The images in this engaging visual history were taken from my historic reprint of a 1904 classic cookbook, The Blue Grass Cook Book — photographs that document culinary contributions to American cuisine and establish an enduring legacy for the women as modern role models who encourage everyone to cook and share real food.

In these times of Top Chef-styled plates where food is stacked, foamed and streaked, it can seem impossible to be impressed by the simplicity of three-course menus comprised of dishes like avocado cocktail, buttered saltines, broiled steak, petit pois, and watermelon ice cream — but we should try.

So, in celebration of the hard-working, nimble chef who taught culinary students how to make homemade vol-au-vent and calas toud chaud while tutoring her daughter in the entrepreneurial skills of business 101, and as part of my outreach to vulnerable children in Austin, and in partnership with the James Beard Foundation, the University of Texas, the Texas Restaurant Association, and Kikkoman, four high school culinary students cooked for a reception featuring chef Scott Barton, April 1 at the Beard House.

For the past three years, students from Pflugerville’s John B. Connally High and Austin’s Travis High have demonstrated professionalism, self-awareness, and pride in the presence of these art works, the kind of outcomes we can expect when we provide culturally-appropriate experiences that engage and inspire kids toward careers in the food industry — whether those jobs are in food archaeology, anthropology, food service, or public health.

Ryan Johnson, a senior at Connally described the meaning of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity this way: “Most people my age have never heard of the James Beard Foundation, or the IACP, but as soon as Chef mentioned those names, I couldn’t believe my ears. I thought. “No way!

“Every night this week, I could hardly sleep because of the anticipation, and thoughts of the different people I’ll meet, and foods I’ll see. My mom always wanted me to be as passionate about food as she is; her wish has come true. I am truly grateful for the wonderful opportunities my passion and hard work have brought me, and I can’t help but think, “I’m actually going to be a chef…”

For information about The Jemima Code exhibit at the James Beard House Greenhouse Gallery, visit:

http://www.jamesbeard.org/index.php?q=greenhouse_gallery

In Her Kitchen

Lena’s Doughnuts

Ingredients

- 2 cups sifted flour

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon each ground nutmeg and cinnamon

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1 egg, well beaten

- 1 tablespoon melted butter

- 1/2 cup milk

Instructions

Sift flour once, measure, add baking powder, salt, nutmeg and cinnamon. Sift together, three times. Combine sugar and egg; add butter. Add flour, alternately with milk, a small amount at a time. Beat after each addition until smooth. Knead lightly 2 minutes on lightly-floured board. Roll 1/3-inch thick. Cut with doughnut cutter. Let rise for several minutes. Fry in deep, hot fat until golden brown. Drain on unglazed paper. Sprinkle with powdered sugar, if desired.

Number of Servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

Comments