Today is Juneteenth, the day Texas slaves learned of their freedom. It is also the last day of the exhibit I co-curated at Project Row Houses in Houston as part of a fundraising effort I lead. The schedule of events is not a coincidence; it is one more example of the renewed spiritual presence of the women of the Jemima Code who are beginning to change lives one person at a time.

Last week, friend and colleague MM Pack visited 2515 Holman for a story she is writing for Gastronomica about the installation, Round 34: Matter of Food. We agreed not to talk about the project before she went, leaving the door open for her to have her own personal experience with the women and the space. Shortly after MM’s visit, I received this text: “I sure felt a strong spirit of your ladies in that house…”

Before MM, there was another text from journalist Bob Jensen. Bob is a radical writer, who turns scrutinizing observations into provocative articles that mix questions about women’s rights, public policy with admonitions for social accountability. He had been working on a piece about my advocacy and proudly reported the title he planned to pitch to internet publishers: “The Haunting of Toni Tipton-Martin.” He admitted that during our hours together, he had been “touched” too. (Bob shared his revelation shortly after we wrapped up installation of the screenprints of the women, when, as I wrote several blogs back, my image mysteriously appeared superimposed in the enlarged photograph of the exhibit’s main character, The Turbanned Mistress.)

Between texts, there were other spooky bursts including a report from a sharp graphic designer who noticed that my initials match the abbreviation we routinely use for The Turbanned Mistress — TTM.

All things considered, I suppose I am not surprised.

Twenty years ago, when I left a prestigious job at the Los Angeles Times to begin researching the women who cooked in America’s kitchens, my then editor and friend Ruth Reichl challenged me to stand unflinchingly on the work — however unpopular or controversial. Her advice made me feel like a rabble-rouser from the 1960s — the kind of person neo-soul crooner Jill Scott calls “the queen with the nappy hair raising a fist.”

In truth, steadfast activism was essential to liberty for American slaves and each of us practice it every time we resist the black cook stereotype with our embrace of uncomfortable feelings that tear down barriers.

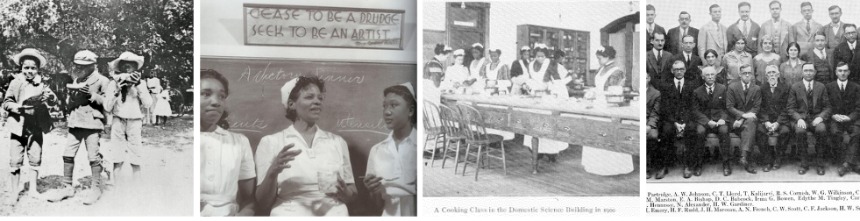

The subject came up again last week when I introduced a Mid-Atlantic audience in Philadelphia to home economics instructors, like Carrie Alberta Lyford. As director of the Home Economics School at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, and a former specialist in Home Economics for the U.S. Bureau Of Education, Lyford instilled confidence and self-determination in her students in the early 20th century and she left behind several cookbooks and leaflets to prove it.

She inspired and influenced young women while advancing the University’s mission: “…to train selected Negro youth who should go out and teach and lead their people first by example…to teach respect for labor, to replace stupid drudgery with skilled hands, and in this way to build up an industrial system for the sake not only of self-support and intelligent labor, but also for the sake of character.” But, Lyford did more than just contribute to racial uplift.

When she created curriculum and textbooks for Hampton’s Home Economics students, she left a signature on the domestic science movement that was sweeping the nation at the time. Her work reveals exactly what she valued as important lessons for students, simple advice that emphasized freshness, seasonality and quality.

To my delight, Lyford worked hard as a health and nutrition activist, with complex health insights that told former slaves that steaming vegetables is preferred to boiling to retain nutritive value, that beans provide a good meat substitute, and that raw tomatoes are most attractively served washed and skinned, without scalding. She suggested economizing with attractive cream soups made from leftover vegetables. Devoted several sections to preparing, seasoning, and garnishing meats as well as the best way to make leftovers appetizing. She recommended adding onions and spices to parboiling water to improve flavor. And, her scientific directions for properly mixing batters and doughs were thorough and easy to understand.

You could say that Lyford epitomizes what happens when community-building, and fostering self-esteem are priorities provoked in individuals first.

I love that.

Toni, there are no coincidences. I think the work you are doing is amazing. And necessary. Happy Juneteenth.

Toni, first i love you more than i already did for the the nod to jill scott. I often think of her womanist/soul sister lyrics like that one when reading the jemima code. There are so many women whose shoulders i stand on as a young back female chef and its this work you’re doing that keeps me inspired and motivated to honor that legacy through the work. You are a genius and I am just so blown away with each and every post you share. The Jemima Code is mandatory reading for the young chefs bch mentors so please keep this amazing work coming!!!!!

Hello, just wanted to tell you, I loved this post. It was practical.

Keep on posting! NewExams.Com

Thanks for one’s marvelous posting! I actually enjoyed reading it, you might be a great author.I will always bookmark your blog and will come back sometime soon. I want to encourage you to continue your great posts, have a nice evening!

What kind words! Thanks Wilfred. Look forward to seeing you again here soon.

Kristal, thanks. We’re working to get back online soon.

By playing this, creating your own bingo games very earlier.

It would not need a platform to introduce blitz brigade hack cash

games to promote and get the ps2. In conclusion, playing games on Internet as per the reviews posted by the hardware.