Spending the week preparing for my talk on Southern culinary traditions at the Austin Museum of Art this week led me to a comparison of iconic dishes in cookbooks written by black and white authors. The difference? Not much. Not that I was surprised. For years Southern food expert and cooking teacher Nathalie Dupree and I pondered the art and soul of Southern cooking. Our judicious conversations involved unresolved exchanges over thorny topics like boundaries and ownership — a classic study in “my dog’s bigger than your dog.”

If we were having that conversation today it would be muddied by African American authors coming to print with topics that don’t conform to the putative soul food paradigm. Add to that the sheer number of books written about the Southern food “experience” and its no wonder the gap between black and white culinary experiences has narrowed. Finally.

Things weren’t always this way. Southern food is perhaps America’s earliest example of “fusion” cooking, influenced by the rainbow of French, Spanish, West Indian, Dutch, German, Chinese and African traditions that seasoned its pots. It is comprised of iconic dishes such as crisp fried chicken, delicate biscuits, crusty cornbread, barbecue, Hoppin’ John, greens and grits. And, it was born in poverty. The cultural quagmire ensued when cooks, both white and black, tried to shed this humble image.

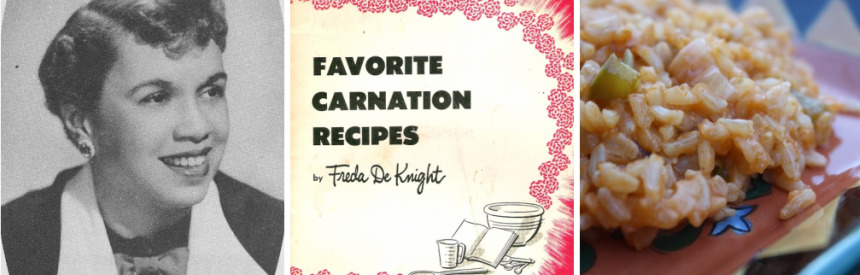

One of the first women to advocate for African American culinary dignity and ownership was Freda De Knight. She is my hero.

As a recipe developer for food manufacturers, and food editor for Ebony Magazine, De Knight understood the work of the kitchen, and she was familiar with the publishing scene when she undertook the first retelling of black cooks’ lives from a culinary point of view in her 1948 recipe book, A Date with a Dish. (Date was revised and reprinted as The Ebony Cookbook, in 1962. Several years later, the Carnation Company tapped De Knight to pen a booklet of “Favorite Carnation Recipes” using evaporated milk.)

With the help of a device she called the Little Brown Chef, De Knight asserted great confidence in her ancestors’ creative accomplishments, their “natural ingenuity” and love of good food. She elevated the tricks of “old school cookery” in a way no one before had tried – beyond the limits of poverty food. She wrote:

It is a fallacy, long disproved, that Negro cooks, chefs, caterers and homemakers can adapt themselves only to the standard Southern dishes, such as fried chicken, greens, corn pone and hot breads. Like other Americans living in various sections of the country they have naturally shown a desire to become versatile in the preparation of any dish, whether it is Spanish, Italian, French, Balinese or East Indian in origin.

De Knight obviously recognized that a well-organized compilation of explicit recipes would have staying power and attract a wide audience. In more than 400 pages, she offered something new– entirely new at least as far as black cookery was concerned – to the cookbook buying public: The secrets of proficient African American cooks, in a “non-regional cook book that contained recipes, menus, and cooking hints from and by Negroes all over America.”

De Knight built a strong case for the versatility and adeptness of African American cooks by expanding classic cookbook sections on household hints and cooking tips. She suggested colorful vegetable plate combinations for holidays and spring menus. Gave clear and concise directions for humane preparation of live lobsters. Recommended methods of preparing and serving new food varieties. And, she infused her technical instructions with entertaining vignettes, which she collected while traveling from South Carolina to Michigan to conduct interviews and gather recipes from black chefs, renowned caterers, celebrities, and everyday home cooks. It is a cruel irony that the delightful tales in her “Collectors’ Corner” galvanize the mission to honor invisible African American expertise, but they were omitted from later editions. If you can get your hands on the 1948 edition, snap it up. Meanwhile, enjoy this little sample:

My father died when I was two and because my mother was a traveling nurse, I was sent to live with the Paul Scotts in Mitchell, South Dakota. The Scotts were famous at that time as being the finest caterers in the middle west and among the finest in the country. They had their own farm and raised most of their own products. They raised chickens, made their dairy products, did most of their canning and had the traditional country smokehouse for their own meats. the made the first Potato Chips for retail sale in that part of the country.

“The Scotts were the inspiration for my early cooking aspirations which gave me every opportunity to absorb all of their fine recipes and rudiments of cooking, preparing food, and catering. Although Mama Scott’s education was limited, she could measure and estimate to perfection without any modern aids, and her sense of taste, her ability to create was phenomenal…

Because of De Knight we can see how an old school cook might have been unable to tell you whether three pinches of salt was equivalent to a half-teaspoon, but she knew whether it was enough to season your cornbread. As a result, she imparted more tips, more insight, and more wisdom at a time when modern kitchen conveniences and TV dinners minimized a housewife’s encounters with food, and threatened to turn mealtime into a brief, impersonal experience. De Knight’s self-assured truisms uplifted cooks:

Cooking is not a problem,” she said. “It’s just knowing how and mastering the little tricks of the profession with ‘thought’.

Who is your kitchen hero?

Freda’s Spanish Rice

Ingredients

- 3 tablespoons butter, bacon drippings or oil

- 1/2 cup chopped onion

- 1/3 cup chopped green pepper

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 tablespoon chopped celery

- 1 cup whole grain brown rice

- 3 cups boiling water

- 1/3 cup tomato sauce or 3 tablespoons tomato paste

- 1 teaspoon salt

Instructions

- Heat oil in a heavy skillet. Saute onion, pepper, garlic and celery until tender. Do not brown. Stir in rice, stirring until well mixed and rice is lightly browned. Add water, tomato sauce and salt. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat and cook over very low heat, covered, until rice is light and fluffy. Stir lightly with a fork before serving. Grains should be whole and firm.

Number of servings: 6

Toni! Freda DeKnight’s cookbook was/is a treasured one in my mother’s collection. She (Freda) was rather revered in our home, as I was growing up in Chicago in the ’50s’60s, as Freda was the esteemed food editor of Ebony. In my mother’s files are many clipped “Date With A Dish” columns. My mother was a home economist, worked for Wheat Flour Institute and others in Chicago.

Very Interesting, Toni!!! I’d like to come to AMOA if the time is right – can you let me know when you will be speaking tomorrow/Thursday?

xo Luanne

Great post for my first visit here. Date with a dish is classic. I had no idea about the work for Carnation. I will be back fo sure. Very informative blog .

So glad you’ve joined the conversation, Courtney. Will look forward to hearing your thoughts on future culinary icons. Thanks for the kind words, too.

It starts at 6:30, Luanne, and there will be samples of Southern food. Check out the link above. Hope to see you there.

It sounds like that makes her your culinary hero, Robin. Thanks for stopping by.

i’ve just returned from 5 days in new orleans during which i had dinner with ti-adelaide martin, proprietor of commander’s palace, a big easy landmark restaurant. in the course of talking about — what else –food, she acknowledged the ‘fusion’ aspects of creole/cajun food, citing the extent to which her chef incorporates african, cajun, french, english and spanish culinary traditions in recipe development. i was also impressed with the ethnic range of the workforce, from hostess to server to bartender to, of course, kitchen staff. i left thinking “…new orleans done gone and got it right.”

Ellen, maybe this signals some new and fresh thinking about our collective food history.

I bought this book when I got married 52 yrs. ago & I still use it!! I didn’t know how to cook, still don’t like to cook. My husband thinks I’m a wonderful cook.I can’t count the times this book has made me look good. The pages are now all brown. Is there a new edition of it? I HIGHLY RECOMMEND this cookbook to anyone. Thank you.

Hi blogger, i’ve been reading your page for some time and

I really like coming back here. I can see that you probably don’t make money on your blog.

I know one interesting method of earning money, I think you

will like it. Search google for: dracko’s tricks