by Toni Tipton-Martin | Dec 30, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

So we went to a cocktail party last night to celebrate the coming of the New Year and the inevitable question came up.

“What do you do?”

I explain that I have just started blogging about the history of African American cooks, and before I can finish my sentence, a woman who looked like she would know better, glared over her glass of Tempranillo and asked, “Why are you still worrying about what happened 200 years ago? It’s in the past; get over it.”

“Well, I can’t get over it,” I scold her. “Neither should you.”

Here’s why:

In 2002, Texas A&M University’s student newspaper, The Battalion, published a political cartoon, which resembled the kind of degrading Jim Crow-era imagery that appeared routinely on manufacturer’s labels, in advertising, magazines, and Southern daily newspapers. Only worse.

The illustration depicted a large black woman wearing an apron, holding a spatula, and chastising her son at TAKS Test time. The Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills exams (TAKS) are serious business for politicians, school districts, and parents in the Lone Star State, and evidently black boys performed pretty poorly that year. Neither the student, nor his or her editor, nor the journalism advisor questioned the suitability of using a bigoted turn-of-the-century image to portray a modern-day mother’s concern for her son’s poor academic performance. I did.

I’d like to agree with the faculty who defended the student’s actions as “an unfortunate mistake” and the woman at the party, who believe that in these “post-racial times” our society does value diversity, abhors “pulling the race card,” and promotes “no color-line” policies, but how can I? The A&M cartoon says that even with re-doubled efforts, our high-technology children cannot see beyond the narrow Aunt Jemima cliché. How can they?

Everywhere you look, the image of African American mothers is stuck in 1900.

Media credentials legitimize journalistic lapses, such as this. Radio disc jockeys like John “Sly” Sylvester” and Don Imus get a pass. Black men in rank drag acts, including Eddie Murphy as Norbit and Tyler Perry as Madea are modern-day re-creations of bigoted minstrelsy and Negro impersonation. And don’t even get me started about the Pine Sol Lady and Lisa from the “Get Mommed” Kleenex ad. It’s as if there was a sign on the casting call door that reads: “Only big girls need apply.”

Please don’t get it twisted; this is not a slam against plus-sized women. What I’m saying is that in the absence of a written history to defy – or at least counter-balance the stereotype – the picture of every African American woman in our national minds’ eye resembles a rude trademark. That shallow image ignored the powerful love language of mother’s kitchen, and even worse, cataloged her skill and virtues as anything but extraordinary in a file marked “idiot savant.”

To be a patient and loving wife and mother; to be smart, talented, hard-working, physically and emotionally strong, yet compassionate; to multi-task: these are the characteristics that intersect in the black women who fed this nation, but they are lost in lampoon.

Which makes two things clear to me: In the year 2010, we need a new picture to replace the Aunt Jemima asymmetry. And, adults like those at A&M who still think that it is appropriate to classify stereotyped imagery as satire should not be teaching anybody. At all.

In order to wrap up this heated conversation with my dinner companion, we take one more trip to the Internet. I tell her about a recent Google search of the culinary cliche “slaving in the kitchen.” I name some of the assorted modern convenience foods, gadgets, and equipment that popped up — all designed to save time and effort in the kitchen — including a Japanese knife called the “kitchen slave,” which offers “simplicity, utilitarian attitude, and beautiful elegance.” Then I contend that the Jemima Code is a uselful, new tool with a similar twist on the theme.

I say that as we enter the season of new priorities and make resolutions to begin this or quit that, we should use this journal to cut through historical rhetoric and expose the wisdom and of poetry of African American culinary artists, to bring their skill and professional excellence into the light.

At last, she relents; the conversation moves on.

So why did I call it the Jemima Code?

Merriam-Webster defines a code as “a body of laws systematically arranged for easy reference; especially one given statutory force; a system of principles or rules (as in moral code); a system of signals or symbols for communication used to represent assigned and often secret meanings.”

To decode, the dictionary goes on to say, is “to convert a coded message into intelligible form; to recognize and interpret a signal; or to discover the underlying meaning of.”

As Americans, we live with all sorts of standardizing codes – dress codes, moral codes, codes of conduct, codes of law, bar codes. Recipes are codes. So are prescriptions. But when we talk about a “Jemima Code,” we see how arrangement of words and images synchronized to classify the character and life’s work of our nation’s black cooks into an insignificant symbol contrived to communicate a powerful double message, based upon exaggerated principles and secret meaning.

Like most codes, the Jemima Code is a 200-year-old system of prejudices and double standards that originated in the hand-written journals and ledgers of slaveholding women and their letters to family and friends. Their inconsistent, emotional observations bloated the image of female house servants. Opinions about those unrealistic behaviors established character types, and those stereotypes transmitted unwritten messages about black cooks that were open to interpretation.

The result was an image America used as powerful shorthand. Aunt Jemima became the embodiment of our deepest antipathy for and obsession with the women who fed us with grace and skill. In short, a sham.

Ironically, the same observations that created this code can break it; the difference is interpretation.

I don’t believe that gratitude for years of servitude, claiming an absolute, single historical truth about black cooks, or redefining culinary processes with black sensibilities will instantaneously remove the haze of hard labor that obscures the real wisdom of their work — a haze that still lingers over modern kitchens. Truth will.

Historian and scholar Sidney Mintz, speaking several years ago at a dinner in Washington, D.C., impelled the idea for this work when he encouraged the audience to find new ways to exalt America’s unsung heroes of the kitchen – the African American cooks.

He said: “We need to honor those women, not only for their achievements as cooks, but also for the terrible burden they bore, standing as they did at the very crossroads where the idle free and the oppressed unfree were joined – in the kitchen. As we do them honor, we have to imagine the restraint, patience, and intelligence they themselves had to possess in order to go home each night to their own families, their men and their children, having lived through another day in the skilled but un-rewarded service of others in whose power they were.”

To ignore these virtues is like eating fried chicken without the skin: You just know something is missing.

Have some…

In Her Kitchen

Pan-Fried Chicken

Ingredients

- 1 (4-pound) frying chicken, cut up

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- 3/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 teaspoon black pepper

- 1/4 teaspoon garlic powder

- 1/4 teaspoon paprika

- Oil

Instructions

Rinse chicken pieces and pat dry. Place flour, salt, pepper and garlic powder in a small paper bag. Add chicken pieces and shake to coat evenly. Let stand 10 minutes. Heat 3/4- to 1-inch oil in a 9 or 10-inch cast iron skillet to about 375 degrees. Add chicken in batches and cook until chicken is crisp and golden brown, about 10 minutes per side. Do not crowd pan. Drain chicken on paper towels. Serve warm.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Dec 23, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

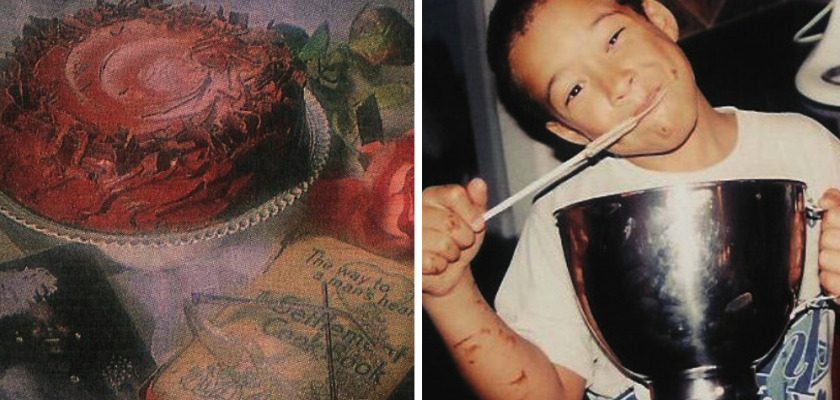

This was supposed to be the blog that explained the origins of The Jemima Code, but when my 17-year-old son Christian asks you to do something, it’s kind of hard not to agree.

Last night, he and five of his friends took possesion of my kitchen, and prepared a seven-course holiday dinner party straight off the pages of Food and Wine. By the time the evening was over, I had learned a lesson about the spirit of giving and about myself. I had to write about it.

Not because I was at all surprised that Christian’s all-male team of non-cooks was planning to prep and serve a holiday feast to strut for the female half of their little group, or even that he composed a classical menu for the occasion. These kids have spent a long fall semester preparing for graduation — writing essays, applying for college, and maintaining outstanding GPAs. They needed to celebrate.

What took my breath away was that he scheduled the party on a day when I would not be home to help. I teach cooking and have a well-stocked kitchen pantry and cookbook library, and my son figured the gig would be easy and sure to impress whether I supervised or not. But these were high school seniors who’ve been cooped up for months with their heads buried in World Geography textbooks. My thoughts didn’t immediately reflect on all of the lovely culinary experiences Chris and I had shared over the years. Instead, I secretly, okay, vocally, pondered whether I needed to distribute parental liability release forms for kids slicing potatoes and fingers on the mandoline, and envisioned Mushroom Veloute splattered everywhere.

Christian offered some sage advice: “Shhhh. Calm down. There are worse things that could happen three days before Christmas — like the tree catches fire or a burglar steals all the gifts.” He said something wonderful, too.

Christian grew up listening to stories about the unsung heroes of the kitchen who I intend to profile here starting in January, and he congratulated me for becoming one of them. He assured me that the self-confidence and discipline he learned were transferrable skills that he would pass on to the guys as they jabbered about mise en place or the proper technique for folding egg yolks and whites together, just the way I had transmitted them to him all these years.

I knew that Christian always really loved to cook. When he was just 2, he would push a chair up to the sink and demand an assignment.

“Cook, cook,” he cooed.

Later, he began making his own special whole wheat pancakes, which were featured in Edible Austin Magazine’s Summer 2009 issue. Christian has also served as my assistant during summer cooking camps, organizing giddy six-year-olds and regaling 6th graders with his Alton Brown imitation.

With this massive dinner party, he confirmed that the love language of my kitchen had taught him patience and how to follow instructions; he also developed some intangible values, such as discipline and encouragement as we nurtured the most disinterested and intimidated novices into cooking from scratch. My brand of kitchen wisdom, he said, had motivated a bunch of really smart guys to devote an entire afternoon to preparing Kansas City Fritters, Caprese Salad, Herbed Roasted Leg of Lamb, Cheese Souffle, and Tarte Tatin as a gift. I was speechless.

I hope the coming stories of some truly fantastic cooks will inspire you into the kitchen, too. In the meantime, Christian’s Herbed Roasted Leg of Lamb, which he adapted from Food and Wine Magazine, is a delicious place for you to start developing a culinary love language of your own.

In Her Kitchen

Herbed Roasted Leg of Lamb

Ingredients

- One (4.5-pound) trimmed, boneless leg of lamb, butterflied

- Extra-virgin olive oil

- 1/4 cup minced flat leaf parsley, plus 2 sprigs

- 1/8 cup minced fresh rosemary, plus 2 sprigs

- 1/8 cup minced fresh oregano, plus 2 sprigs

- 1 small clove garlic, minced

- Salt, pepper

- 4 small baking potatoes, peeled and quartered

Instructions

Preheat the oven to 375 degrees. Open the leg of lamb on a work surface, fat side down. Drizzle with olive oil and rub in the herbs and garlic. Season with salt and pepper. Roll up the lamb, fat side down, and tie with kitchen twine at 1-inch intervals. Season with salt and pepper. Spray a small roasting pan with nonstick vegetable spray. Place herb sprigs in the bottom of the pan. Top with potatoes. Place roast on top and roast for about 1 hour, or until a thermometer inserted into the meat registers 125 degrees for medium-rare. Transfer to a carving board, tent with foil and let rest for 15 minutes. Strain the juices into a cup and skim off the fat. Discard the strings and thinly slice the roast. Drizzle with the juices and serve with potatoes.

Number of servings: 8

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Dec 16, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

I am a Disney girl and everyone knows it. So when the studio announced its intention to release a film with an African American princess, who also happens to be an aspiring chef, I couldn’t have been more excited. I raced to the theater for opening weekend, though I must admit sensing a dark cloud of dread hovering over me as I anticipated the complaints of internet reviewers, and braced for more stereotypes of African American cooks.

After all, this is the same studio that embedded subtle racism in Dumbo and the Jungle Book. And, in the 1950s, Disneyland promoted the Aunt Jemima trademark in its popular restaurant, Aunt Jemima’s Pancake House. Over the years, I was able to overlook those as flaws in a machine that bowed to the social and cultural pressures of its time. But in these “post-racial times, I wondered how they would deal with the New Orleans of 1920 and the limited career options for women of color.

Despite some age-old characterizations about the south and the kitchen in the storyline, critics are gushing, movie-goers pushed the movie to the top of the weekend box-office, and I found the film to be a charming mix of fact and fantasy.

To my surprise, Tiana possesses several of the qualities of the women who will be featured in this journal: she is hard-working with culinary proficiency that is seductive and in high-demand; she has entreprenurial ambitions and skills; she is focused and determined, not waiting around to be rescued by Prince Charming; she is prudent, saving her pennies for a long-term goal (Tiana’s restaurant), she has a very popular cookbook; makes a mean pot of gumbo, and she works selflessly at times to promote the greater good.

Too bad she also is the first Disney princess to spend most of her screen time as an amphibian.

It was also difficult to embrace the image of poverty reflected in Princess Tiana’s Cookbook for children. The book has been sold out for weeks at the Disney store where I live, but her father’s famous recipe for gumbo is posted on Amazon. Unfortunately, the recipe perpetuates the same make-do stereotype of African American cooking that has been promoted for years with its wieners in the mix.

We’ll serve this gumbo over the holidays, instead.

In Her Kitchen

Chicken Gumbo

Ingredients

- 1/2 cup all-purpose flour

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/2 teaspoon garlic powder

- 1/4 teaspoon black pepper

- 1/4 teaspoon cayenne red pepper

- 1 (3- to 4-pound) chicken, cut up

- 1 tablespoon each butter and oil

- 1 1/2 cups chopped onions

- 1/4 cup chopped green onions

- 1 cup chopped green bell peppers

- 1 cup chopped celery

- 1 tablespoon minced garlic

- 1 pound smoked sausage, sliced

- 2 quarts chicken broth

- 2 bay leaves

- 2 tablespoons minced fresh parsley

- Hot cooked rice

Instructions

- Place flour in a cast-iron skillet in a 400 degree oven until the flour turns nut-brown, stirring often. Combine seasonings and sprinkle chicken pieces on both sides. Heat butter and oil in a heavy Dutch oven or soup pot. Add a few chicken pieces to the pan cook over medium-high heat until brown. Turn and cook on other side. Do not crowd the pan. Continue cooking and turning chicken until all pieces are done. Remove to a platter and set aside. Add onions, bell peppers, celery and garlic to pan, and cook over medium heat, stirring to loosen browned bits. Add sausage to pan and increase heat to high. Saute 5 minutes longer, until vegetables are slightly browned and carmelized. Meanwhile, place browned flour in a medium-sized bowl. Gradually whisk in 2 cups broth, stirring until flour is completely dissolved and no lumps remain. Add to vegetables along with remaining 6 cups broth and bay leaves. Reduce heat and let gumbo simmer 45 minutes. Do not boil. Use a slotted spoon to remove chicken from pot. Let cool slightly, then remove chicken from the bone and cut into bite-sized chunks. Remove and discard bay leaf. Return chicken to pan, sprinkle with parsely and season to taste with additional salt and pepper. Serve over hot cooked rice.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Dec 9, 2009 | Kitchen Tales

My grandmother Nannie was a sturdy woman of Choctaw decent who cooked the most delicious food, but she passed on without leaving me a single morsel of the culinary wisdom and life lessons my mother’s generation took for granted. And, yet, her raspy voice of affection still whispers two things to me: security and chocolate cake.

My family spent the years before I turned six, living with Nannie in her modest two-bedroom home. When I wasn’t perched on the branches of the towering avocado tree that shaded Nannie’s backyard like a 100-year-old oak, I was being lured into her kitchen by the intoxicatingly sweet cocoa perfume of a bubbling mixture as it percolated in the top of her Pyrex double boiler. Nannie saw my desperate anticipation for even a tiny taste, wiped her hands on the yellow gingham apron her twin sister Jewel had sewn for her – the one with the torn pocket and border of delicate garnet strawberries – leaned forward and handed me the bowl. I don’t remember much about the cake, but raw batter still seduces me today. And, the memory makes me feel warm, comforted, and strangely secure, even though I’m not a little girl anymore.

Several years ago, we developed a recipe and this photograph for Nannie’s Devil’s food cake in the Los Angeles Times’ Test Kitchen, which first brought the memories of her kitchen flooding back. Basking in the warmth of those special moments made me realize that many of my memories at the table with Nannie had been suffocated. Somehow over the years, I lost touch with the woman who would have been my very own personal culinary counselor, helpmate, and role model. Even with all that I knew about kitchen skill and kitchen dirty work, and “practice makes perfect,” I still developed the wildy unrealistic view of her as some kind of “kitchen magician.” I got caught up in the notion that she was a natural-born culinary genius to be iconized, not a specialist to emulate.

A list of culinary cues from Nannie’s kitchen should have revealed a remarkable competence and told me that she cooked with her head, as well as her heart and her senses. In her kitchen, fingertips were the preferred instruments to measure a teaspoonful. She didn’t need the latest silicon-coated kitchen timer to tell her when it was time to turn the fried chicken; she knew just by the gurgling sound coming from the skillet. The sweet perfume wafting from the oven signaled that the pound cake was done baking. And, she scrambled delicate eggs in cast iron without any back up from Teflon. Instead, thinking about her intimidated me.

So I decided to make the cake again, following the yellowed recipe she tore from a magazine, and buried in the back pages of her favorite cookbook. It turns out the cake I naievely thought Nannie just whipped from her imagination, came from the Noble-Purefoy Hotel in Anniston, Alabama — a decadence that was lovely to look at, but its dense cocoa layers didn’t translate well into this century. Too many years of eating commercial birthday cakes, hurry-up cake mixes, and bakery goodies, I guess.

Nannie is gone and I’m still perfecting her recipe, and I adapted this Double Chocolate Fudge Cake from different recipes for fudgey pound cakes as a decadent conversation starter that lets me tell my kids about Nannie and the other members of her humble sorority. Now, my boys lick the beaters and the bowl clean.

In Her Kitchen

Double Chocolate Fudge Cake

Ingredients

- 5 ounces unsweetened chocolate

- 2 cups sifted all-purpose flour

- 1 teaspoon baking soda

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 cup instant coffee or espresso

- 2 tablespoons boiling water

- 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons cold water

- 1/2 cup orange rum

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- 1 cup unsalted butter

- 2 cups sugar

- 4 eggs

- Shortening

- Unsweetened cocoa powder

- Bittersweet Chocolate Glaze

Instructions

- Melt the chocolate in the top of a double boiler set over hot, not boiling, water. Remove chocolate before it is completely melted and stir until smooth. Set aside off heat.

- Stir together flour, baking soda and salt and set aside. In a 2-cup measuring cup, dissolve the instant coffee in the boiling water. Stir in the cold water, rum and vanilla and set aside.

- In the bowl of an electric mixer, cream together butter and sugar until mixture is light and fluffy. Beat in eggs, one at a time, beating well and scraping down the sides of the bowl after each addition. With machine running, gradually pour chocolate mixture down the sides of the bowl and beat until smooth. Add flour and coffee mixture to batter in 3 batches, beginning and ending with flour. Beat until smooth, but do not overmix. Batter may look slightly curdled.

- Grease a 10-cup bundt or tube pan and dust with unsweetened cocoa powder. Bake at 325 degrees 1 hour and 10 minutes, or until a wood pick inserted in the center comes out clean. Do not overbake.

- Cool cake on a wire rack for 15 minutes, then invert onto another rack to cool completely.

- Drizzle cake with Bittersweet Chocolate Glaze.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

In Her Kitchen

Bittersweet Chocolate Glaze

Ingredients

- 12 ounces bittersweet chocolate, broken into pieces

- 7 tablespoons hot water

Instructions

- Melt the chocolate in the top of a double boiler set over hot, not boiling water. Stir until smooth. Whisk the water into the chocolate all at once, whisking until the chocolate is smooth and shiny. It will have the texture of softly whipped cream.

Number of servings: 12

In Her Kitchen

Comments