by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jan 27, 2015 | Featured, Uncategorized

This will be the last regular post for The Jemima Code — a blog that turned the spotlight on America’s invisible black cooks and their cookbooks, grew into a traveling exhibit and book available now via the University of Texas Press and spawned a 501c3 nonprofit organization. Three new initiatives, inspired by current events, will take its place.

Over last year’s Thanksgiving weekend, an MSNBC segment with Melissa Harris-Perry shifted attention from outrage and protests over racial profiling in Ferguson, Mo. to racial stereotyping in the food world. The topic of discussion: food, race and identity. Using Jim Crow era imagery and ignored culinary history as the backdrop, a panel of experts introduced viewers to a surprisingly academic food justice dialogue, raising a question black food professionals wrestle with all the time:

What we can learn about who we are when we shake off the shame about how or what we eat?

The gathering included Psyche Williams-Forson, author of Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, & Power, and directed some much-needed attention to the idea of reclaiming ancestral foods as a source of cultural pride. Williams-Forson, whose illuminating scholarship examines the complex relationship between racist and realistic characterizations of our food traditions, acknowledged the destructive legacy associated with negative images of African American food choices. The insightful scholar also pointed to positive aspects of her affirming work that encourage black women to embrace the myriad ways our foremothers used food for economic freedom and independence, community building, cultural work and to develop personal identity.

Take watermelon and fried chicken for instance. Some black folks feel demonized when they eat these foods in public, while chefs in trendy restaurants all around the country earn high dollars for watermelon salad and gluten-free gospel bird. And don’t even get me started talking about the book and blog that made white authors household names when they capitalized on the label “thug” and its new meaning — symbolizing “a slice of the African American urban underclass by others privileged to define them, label them, and take their lives…,” as Michael Twitty stated, while black authors struggle to secure publishing contracts. (You’ll have to read his blog post and the comments about Thug Kitchen on Afroculinaria.com to get the scoop.)

Even with evidence pointing to valuable African American foodways, the discussion ended with frustration as MHP exclaimed: “I feel like we just need to bring joy to eating all of it.”

It was as if “nerdland’s” exasperation (MHP’s self description) parted the Red Sea, offering freedom to culinary history’s slaves through new projects for The Jemima Code.

The first is a follow-up cookbook that Rizzoli will publish in 2016. The Joy of African American Cooking features 400 to 500 recipes tested for today’s home kitchen, tracing the history of dishes created by African American cooks over three centuries, including influences of Africa, the Caribbean, and the American South.

The John Egerton Prize I received from Southern Foodways Alliance inspired what came next. On Juneteenth weekend 2015 we held the first symposium dedicated exclusively to African American foodways in Austin, Texas. The event gathered scholars, researchers, students, journalists, authors, restaurateurs, farmers, chefs, activists, and anyone interested in exploring issues of social injustice through the lens of food for Soul Summit: A Conversation About Race, Identity, Power and Food.

The activities began on Emancipation Day (June 19) with a reception hosted by Leslie Moore’s Word of Mouth Catering with wines by Dotson-Cervantes and the McBride Sisters. We spent the next day and a half eating and drinking together on the grounds of Austin’s Historic Black College Huston-Tillotson University, while discussing the complex intersection of African American foodways traditions and how they have been used to define culture. Well-known and respected African American food industry experts including Jessica B. Harris, Twitty and the soul food scholar, Adrian Miller challenged our thinking about the foods that comprise the traditional African American diet, the ways those foods and the people who prepared them have been characterized and the impact of those representations on our communities. We explored the ways food continues to shape economic opportunities and community wellness and what some folks are doing about it. Renown African American chefs and mixologists, including Bryant Terry, Todd Richards, Kevin Mitchell, BJ Dennis and Tiffanie Barriere excited our palates with traditional, modern, and vegan fare. You can hear highlights, recorded in part, by a grant from Humanities Texas and Imperial Sugar, on SoundCloud.

Finally, I know that everyone can’t open the doors to a restaurant honoring the food and memory of a fabulous cook and relative the way that chef Chris Williams does every week with upscale, bowl-licking shrimp and grits at Lucille’s in Houston. So instead, I hope to reduce food shaming and “bring joy” to cultural eating through an online living cookbook and public archive that also picks up where The Jemima Code’s expanded history leaves off.

It is under construction now, but when business and sociology students are done with it this summer, the website will invite people of every culture to log-in, share recipes, photos, and stories about their favorite invisible cook. In my vision, this diverse group of “Jemimas” will turn the spotlight onto individuals so we can begin to embrace one another without prejudice or as members of a group associated with a particular race or food tradition.

If that’s not enough to spur joy in African American cooking, the comment section will remain open for other suggestions.

Discuss!

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jun 20, 2014 | Featured, Kitchen Tales

What do you do when you discover something unknown to most people? You make a documentary, of course. At least that’s what my friend Adrian Miller has decided to do, and I hope you will support his very special project.

In my February 28th post, I introduced you to Adrian and urged you to read his book Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time. Since then, Soul Food won the 2014 James Beard Foundation Award for Reference and Scholarship, and just this week, Addie Broyles interviewed us for an Austin-American Statesman feature story about Juneteenth foods, including red soda water. In September, Adrian and I will share the stage at the Eat. Drink. Write. Memphis., in Tennessee, and we’re hoping to tell the story of America’s invisible black cooks next spring in Washington, D.C.

But today, I want to tell you about Adrian’s next important work: a television documentary about African American presidential chefs.

While writing Soul Food, he discovered that every U.S. president has had an African American working in their kitchen, and he’s got their stories and recipes. Adrian will profile several women (pictured above) who cooked for Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison (Dolly Johnson, circa 1887, left), Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt (Elizabeth “Lizzie” McDuffie, maid and part-time cook), and Lyndon Johnson (Zephyr Wright). (You can read more about these cooks in an essay Adrian wrote for our friend Ramin Ganeshram’s America I Am Pass It Down Cookbook.)

It’s no surprise to me that the Jemima Code runs through the White House basement!

Adrian has an active Kickstarter campaign for this documentary, tentatively titled, The President’s Kitchen Cabinet. His idea is to film a trailer that can be used to pitch the show to television network executives. He’s already raised more than 75% of the $10,000 goal, and now the campaign is in its final days (ends at midnight on June 26th).

Ordinarily, it is enough for me to share the stories of amazing women (and a few men) and their gifts to American cuisine on this blog. And, I might even give you a cute little red sticker, emblazoned with the declaration “Bringing Back the Bandana” as your badge of ambassadorship when you attend a Jemima Code talk and are moved by its hopeful message of racial reconciliation at table.

But this week, as we celebrate Juneteenth and its promise of a better tomorrow, I’m asking that you please take a moment to check out Adrian’s Kickstarter campaign, make a donation (no matter how small), and share it with others.

Together, we can help get this important work on the air in time for President’s Day 2016!

by Toni Tipton-Martin | Jun 19, 2011 | Uncategorized

Today is Juneteenth, the day Texas slaves learned of their freedom. It is also the last day of the exhibit I co-curated at Project Row Houses in Houston as part of a fundraising effort I lead. The schedule of events is not a coincidence; it is one more example of the renewed spiritual presence of the women of the Jemima Code who are beginning to change lives one person at a time.

Last week, friend and colleague MM Pack visited 2515 Holman for a story she is writing for Gastronomica about the installation, Round 34: Matter of Food. We agreed not to talk about the project before she went, leaving the door open for her to have her own personal experience with the women and the space. Shortly after MM’s visit, I received this text: “I sure felt a strong spirit of your ladies in that house…”

Before MM, there was another text from journalist Bob Jensen. Bob is a radical writer, who turns scrutinizing observations into provocative articles that mix questions about women’s rights, public policy with admonitions for social accountability. He had been working on a piece about my advocacy and proudly reported the title he planned to pitch to internet publishers: “The Haunting of Toni Tipton-Martin.” He admitted that during our hours together, he had been “touched” too. (Bob shared his revelation shortly after we wrapped up installation of the screenprints of the women, when, as I wrote several blogs back, my image mysteriously appeared superimposed in the enlarged photograph of the exhibit’s main character, The Turbanned Mistress.)

Between texts, there were other spooky bursts including a report from a sharp graphic designer who noticed that my initials match the abbreviation we routinely use for The Turbanned Mistress — TTM.

All things considered, I suppose I am not surprised.

Twenty years ago, when I left a prestigious job at the Los Angeles Times to begin researching the women who cooked in America’s kitchens, my then editor and friend Ruth Reichl challenged me to stand unflinchingly on the work — however unpopular or controversial. Her advice made me feel like a rabble-rouser from the 1960s — the kind of person neo-soul crooner Jill Scott calls “the queen with the nappy hair raising a fist.”

In truth, steadfast activism was essential to liberty for American slaves and each of us practice it every time we resist the black cook stereotype with our embrace of uncomfortable feelings that tear down barriers.

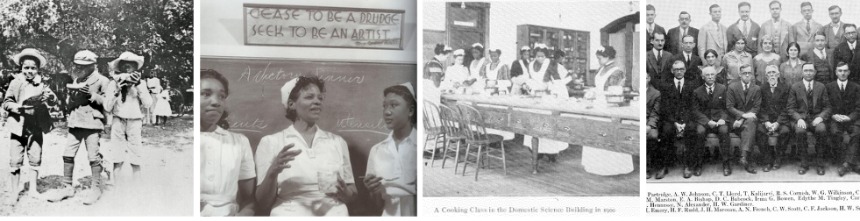

The subject came up again last week when I introduced a Mid-Atlantic audience in Philadelphia to home economics instructors, like Carrie Alberta Lyford. As director of the Home Economics School at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, and a former specialist in Home Economics for the U.S. Bureau Of Education, Lyford instilled confidence and self-determination in her students in the early 20th century and she left behind several cookbooks and leaflets to prove it.

She inspired and influenced young women while advancing the University’s mission: “…to train selected Negro youth who should go out and teach and lead their people first by example…to teach respect for labor, to replace stupid drudgery with skilled hands, and in this way to build up an industrial system for the sake not only of self-support and intelligent labor, but also for the sake of character.” But, Lyford did more than just contribute to racial uplift.

When she created curriculum and textbooks for Hampton’s Home Economics students, she left a signature on the domestic science movement that was sweeping the nation at the time. Her work reveals exactly what she valued as important lessons for students, simple advice that emphasized freshness, seasonality and quality.

To my delight, Lyford worked hard as a health and nutrition activist, with complex health insights that told former slaves that steaming vegetables is preferred to boiling to retain nutritive value, that beans provide a good meat substitute, and that raw tomatoes are most attractively served washed and skinned, without scalding. She suggested economizing with attractive cream soups made from leftover vegetables. Devoted several sections to preparing, seasoning, and garnishing meats as well as the best way to make leftovers appetizing. She recommended adding onions and spices to parboiling water to improve flavor. And, her scientific directions for properly mixing batters and doughs were thorough and easy to understand.

You could say that Lyford epitomizes what happens when community-building, and fostering self-esteem are priorities provoked in individuals first.

I love that.

Comments