SHEILA FERGUSON: “Aunt Ella’s Recipes Speak for Themselves”

“Rise up, ye women that are at ease! Hear my voice ye careless daughters! Give ear to my speech.”

— Isaiah 23:9

You may have been surprised to see so few posts about women last month on a blog that is named after a woman.

From memorable historic figures, to my friends Michael Twitty and Adrian Miller, February was a time to celebrate the achievements of male African American food industry professionals — written history makes it so much easier to report the culinary accomplishments of men. W. E. B. Dubois, for example, praised male caterers in his sociological study, The Philadelphia Negro, while the personal papers of Presidents Washington and Jefferson elevated male kitchen workers from slave to chef status — ignoring Edith Fossett’s legacy of French cuisine, once characterized by Daniel Webster as “good and in abundance.”

It is time to get back to The Ladies.

To celebrate Women’s History Month, the Jemima Code exhibit hits the road tomorrow, sharing life-changing culinary truths, and rewriting black women’s history, one recipe and one audience at a time.

Our first stop is part of a series of events hosted by the University of North Carolina – Charlotte’s Center for the Study of the New South, which will explore the history of race in southern kitchens and includes a two-day conference in September entitled: “Soul Food: A Contemporary and Historical Exploration of New South Food.” Then we are off to Chicago for the 36th annual conference of the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP).

“The Jemima Code fits into the Center’s study of new south food by bringing life to the untold history, triumphs and struggles of one of the primary groups, African American women, associated with what we call southern food,” said Jeffrey Leak, director of the Center and Associate Professor of English. In presenting the Jemima Code in multiple settings — campus, church, and museum — the University hopes to demonstrate its commitment to community engagement and to sharing knowledge with other institutions in the community, Leak explained. “In doing so, we create the possibility of improving upon or creating relationships with these institutions that will lead to collaborative approaches to some of our communities most difficult challenges.”

Jemima Code events kick off with a talk and tea hosted by UNCC and the Social Justice Ministry at Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, featuring the memories of a former slave from Asheville, Fannie Moore. In her WPA interview, Moore details the family technique for preserving peaches showing us how slaves practiced local, seasonal, organic and sustainable living and underscoring the message: “claim your heritage to reclaim your health.”

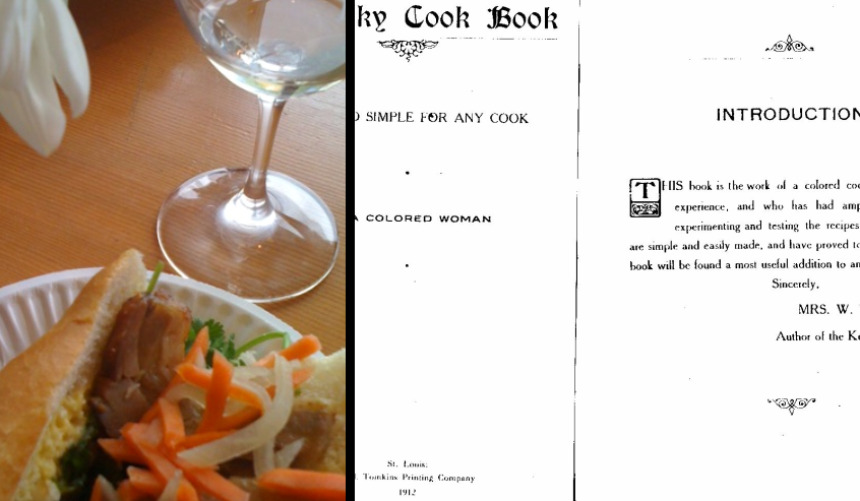

Next, we’re off to a meeting with students in UNCC’s College of Liberal Arts & Sciences focused on a few ways recipes and cookbooks preserve identity. We will uncover evidence of entrepreneurial and personal values like industriousness and discipline in Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which the former slave observed in her grandmother, a cookie vendor.

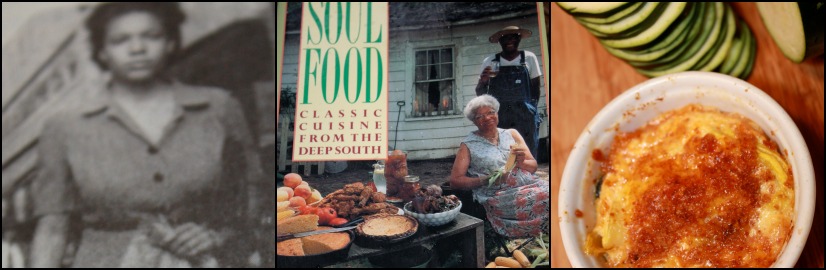

On Monday, at an intimate reception, conversation and Jemima Code exhibit at the Levine Museum of the South, guests will be surprised and amazed by African American kitchen proficiencies in stories told by author and R & B singer Sheila Ferguson.

In her 1989 cookbook, Soul Food Classic Cuisine from the Deep South, the former lead singer for the Three Degrees writes in a fast-talking, jive-style that is complete with snappy expressions and memories of cooking and eating at home with family and friends. She has a theory that cooking the soul food way means “you must use all of your senses. You cook by instinct, but you also use smell, taste, touch, sight, and particularly, sound…these skills are hard to teach quickly. They must be felt, loving, and come straight from the heart and soul.” To prove it, she esteems family members, including her Aunt Ella from Charlotte, writing about brilliant dishes of animal guts smothered with rich cream gravy in a colorful rhythm that might just make you want to run out and trap a possum. For real.

Finally, a conversation at IACP on March 16 will explore lessons in culinary justice taught by iconic Chicagoland cookbook authors, like Freda DeKnight. Food writer Donna Pierce helps me set the table with her research on the culinary industry’s middle class. We wrap up with an interactive workshop that I hope will spur Jemima Code audiences to enact what they discover about black cooks, with inspiration from these adapted words of abolitionist Lydia Maria Child:

“For the sake of my culinary sisters still in bondage…”

Aunt Ella’s Squash Bake with Cheese

Ingredients

- 5 cups sliced thin-skinned yellow squash

- 3 tablespoons butter or margarine

- 1/4 cup chopped green pepper

- 1/4 cup chopped onion

- 1/4 cup chopped celery

- 1 (10.5-ounce) can cream of mushroom soup

- 1 egg, slightly beaten

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 teaspoon black pepper

- 1/2 cup grated Cheddar cheese

- 1/4 cup fresh breadcrumbs

- Paprika, optional

Instructions

Cook the squash in 1/4 to 1/2 cup water for 10 to 15 minutes or until fork tender. Drain well and puree it. Melt 2 tablespoons butter in a skillet over medium yeat and sauté your onion, celery, and green pepper until soft, about 5 minutes. Add the soup, undiluted, and cook, stirring constantly, until the soup is smooth and well-blended with the vegetables.

*Serves 6-8

Preheat your oven to 375 degrees.

In a medium-sized bowl, mix but do not beat your squash puree, soup and vegetable mixture, with the egg, salt, pepper, and half of the cheese. Pour into a well-greased 1 1/2 quart baking dish. Mix the remaining butter with the breadcrumbs and the rest of the cheese, and spread this over the top of the squash. Sprinkle with paprika if desired. Bake in the oven for 35 to 45 minutes or until your squash bake is brown and bubbly.

Variation: Do not puree squash. Substitute evaporated skim milk, 2 eggs and 1-2 tablespoons melted butter for the canned soup and 1 egg.

Aunt Ella is one of the finest soul food cooks in our family and she makes squash taste like something out of this world. If you can’t find the right kind of squash this is almost as good made with courgettes.

Adapted from Soul Food: Classic Cuisine from the Deep South, by Sheila Ferguson

Comments